‘Poor Service’ Drives STB’s Proposed Reciprocal Switching Rule (Updated, TD Cowen Commentary)

Written by Marybeth Luczak, Executive Editor

The Surface Transportation Board (STB) on Sept. 7 issued a Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (NPRM) that it said focused on “providing rail customers with access to reciprocal switching as a remedy for poor service.” It called the move “an important step in addressing the many freight rail service concerns expressed by stakeholders since 2016.” Comments are due by Oct. 23, and STB said it anticipates “acting expeditiously” on the proposal.

“In the past several years, and particularly since 2021, it has become clear that many rail customers nationwide have suffered from inadequate and deteriorating rail service,” STB Chairman Martin J. Oberman said during the announcement of the NPRM (download below), which the Board members issued by unanimous vote. “These problems were documented in detail in the hearings conducted by the Board in April 2022 … The Board has continued to closely monitor the state of rail service.

“For this reason, the Board has determined to focus its efforts with respect to reciprocal switching on providing relief to rail customers suffering from poor service. With the issuance of today’s NPRM, the Board is proposing that one approach to improving rail service is to afford affected shippers the opportunity to obtain a reciprocal switch to a competing Class I carrier when service falls below a standard set in the proposed rule.

“The new rule contains a distinct advantage over both the existing regulations and the proposal in the 2016 NPRM [Docket No. EP 711 (Sub-No. 1)]. The proposed new rule sets specific, objective and measurable criteria for when prescription of a reciprocal switching agreement will be warranted. This rule will bring predictability to shippers and will provide Class I carriers with notice of what is expected of them if they want to hold on to their customers who might otherwise be eligible to obtain a switching order. As a result, litigation costs to obtain a switch should be greatly reduced and petitions to obtain a switching order should be able to be litigated much more swiftly.”

The Sept. 7 release of the NPRM closes Docket No. EP 711 (Sub-No. 1) and proposes, in a new Subdocket (Docket No. EP 711 [Sub-No. 2]), a new set of regulations.

According to the STB, the newly proposed regulations would provide “a streamlined path for the prescription of a reciprocal switching agreement when service to a terminal-area shipper fails to meet any of three performance standards.” The proposed standards, it explained, “are intended to reflect a minimal level of rail service below which a shipper would be entitled to relief, and each standard would provide an independent path for a petitioner to obtain prescription of a reciprocal switching agreement.” STB said they are “intended to be unambiguous, uniform standards that employ Board-defined terms and are consistently applied across Class I rail carriers and their affiliated companies.” The three STB-proposed standards are:

1. Service Reliability. This is defined as the “measure of a Class I rail carrier’s success in delivering a shipment by the original estimated time of arrival (OETA) that the rail carrier provided to the shipper,” according to the federal agency. STB reported the “OETA would be compared to when the car was delivered to the designated destination and would be based on all shipments over a given lane over 12 consecutive weeks.” One proposed approach, STB said, “would be to set the success rate during the first year after the rule’s effective date at 60%, meaning that at least 60% of shipments arrive within 24 hours of the OETA, and increasing the success rate thereafter to 70%.” STB said it also seeks comment on other approaches, such as “maintaining the required success rate at 60% permanently or raising it to higher than 70% after the second year.” Phasing in a higher success rate over time, STB said, would provide the Class I railroads “with time to increase their work forces and other resources, or to modify their operations, as necessary, in order to meet the required performance standard.”

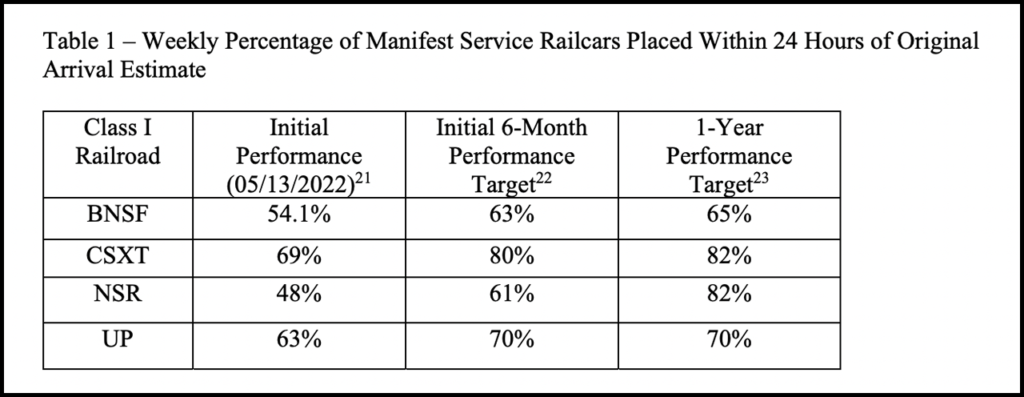

In the NPRM, STB wrote that “as a starting point for possible percentages in the service reliability standard, the Board notes that [a little more than a week after its April 26-27, 2022, “Urgent Issues in Freight Rail Service” hearing,] … it directed BNSF, CSXT, NSR, and UP [in Docket No. EP 770 (Sub-No. 1)] to provide an indicator and target for trip plan compliance (TPC) as well as weekly data measuring manifest service, unit trains, and intermodal traffic placed at destination 24 hours past OETA … Although the carriers refer to the TPC indicator by different names and measure performance in different ways, these four carriers reported the below initial TPC metrics for manifest traffic (the largest category of non-intermodal traffic), initial six-month performance targets, and one-year performance targets”:

“While the Board recognizes that these figures are system averages, each of the four carriers required to submit service recovery plans has acknowledged that their service fell short of public expectations or needs during the time when the carriers reported their initial performance levels,” it wrote. “The Board finds that the carriers’ performance levels during this challenged time are a reasonable starting point for setting standards for inadequate service and, as such, has used these levels to formulate proposals for potential performance standards under part 1145.”

2. Service Consistency. STB said this is the “measure of a rail carrier’s success in maintaining, over time, the carrier’s efficiency in moving a shipment through the rail system.” The service consistency standard, according to the agency, “is based on the transit time for a shipment, i.e., the time between a shipper’s tender of the bill of lading and the rail carrier’s actual or constructive placement of the shipment at the agreed-upon destination.” STB’s NPRM proposes that, “for loaded cars, unit trains and empties, a petitioner would be eligible for relief if the average transit time for a shipment increased by a certain percentage—potentially 20% or 25%—as compared to the average transit time for the same 12-week period during the previous year,” according to the agency.

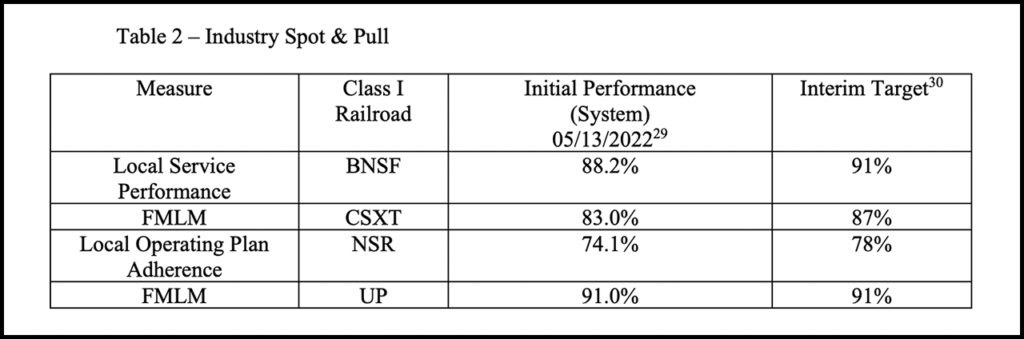

3. Inadequate Local Service. STB defined this as the “measure of a rail carrier’s success in performing local deliveries (‘spots’) and pick-ups (‘pulls’) of loaded railcars and unloaded private or shipper-leased railcars within the applicable service window, often referred to as ‘industry spot and pull’ (ISP).” The NPRM proposes that a railroad would “fail the standard” if it had an ISP success rate of less than 80%, over a period of 12 consecutive weeks, in performing local deliveries and pick-ups within the applicable service window. “The ISP success rate would measure whether the carrier provides the service within its customary operating window for the affected shipper, which in no case can exceed 12 hours,” STB said. “This service metric provides rail customers with the long sought-after information on all important first mile/last mile service.”

In the NPRM, STB provided the following table:

“Although the carriers refer to industry spot and pull indicators by different names (e.g., Local Operating Plan Adherence or LOPA) and measure performance in different ways, these four carriers first reported ISP metrics and interim targets for manifest traffic,” STB explained. “While the Board recognizes that these figures are system averages, each of the four carriers that were required to submit service recovery plans [following the “Urgent Issues in Freight Rail Service” hearing] have acknowledged that their service fell short of expectations during the time when the carriers reported their initial performance levels. As such, these averages are a reasonable starting point for setting standards for poor or inadequate local service.”

According to STB, the proposed rule would require all Class I’s to provide their customers with “the historical data for these [three] service metrics within seven days of a customer’s request” so that customers can “readily monitor and measure their rail service.” It also provides for “affirmative defenses for service failures resulting from issues beyond the rail carrier’s control, such as natural disasters or actions of third parties,” STB reported.

“Importantly, for the first time, the proposed rule also would require all three service metrics be standardized across all Class I carriers,” said STB, adding that it also “proposes to make permanent certain data reporting requirements relevant to service reliability and inadequate local service currently being collected on a temporary basis” under Docket No. EP 770 (Sub-No. 1).

In the NPRM, STB wrote that its permanent collection of this data would be adapted as follows: “The Class I carriers would be required to provide to the Board on a weekly basis: (1) for shipments moving in manifest service, the percentage of shipments for that week that were delivered to the destination within 24 hours of OETA, out of all shipments in manifest service on the carrier’s system during that week; and (2) for each of the carrier’s operating divisions and for the carrier’s overall system, the percentage of planned service windows during which the carrier successfully performed the requested local service, out of the total number of planned service windows on the relevant division or system for that week.”

Additionally, STB said it proposes that reciprocal switching agreements “would be for a minimum period of two years and up to a maximum of four years, depending on the evidence presented.” But it is seeking comment on whether a longer period is necessary “to ensure the rule’s effectiveness.” STB pointed out that the reciprocal switching agreement could be terminated at the end of the prescribed period “if the incumbent rail carrier proves to the Board that it can provide service meeting the pertinent minimum standard going forward. If it fails to do so, the reciprocal switching agreement would remain in place.”

STB Member Robert Primus, summed up in a separate concurring expression, that the NPRM “sets forth a promising new way to institute reciprocal switching when it is ‘practicable and in the public interest.’” The proposal “appears to be an improvement over the 2016 NPRM’s application of the public interest prong, and I look forward to the development of a comment record on it,” he wrote. “I eagerly anticipate the Board’s action to improve access to the statute’s other prong, addressing reciprocal switching that is ‘necessary to provide competitive rail service.’ Rail customers have interpreted the standard in 49 C.F.R. § 1144.2—under which a reciprocal switching order requires a determination that it is ‘necessary to remedy or prevent an act that is contrary to the competition policies of 49 U.S.C. 10101 or is otherwise anticompetitive’—as setting an unrealistically high bar … As a result, no petitions for reciprocal switching have been filed for many years, despite rail customers’ expressions of concern about competition. The Board should act soon to ensure that reciprocal switching is available for competitive access to the extent authorized by the language of the statute.”

Industry Response

Shortly after the NPRM was released, Association of American Railroads President and CEO Ian Jefferies issued the following statement: “The withdrawal of the ill-conceived 2016 forced switching proposal is a positive development, as the extensive record developed by this Board on that proposal clearly demonstrated that it was both unwise and unworkable. In its place, the Board has proposed a new, service-based approach, which AAR is reviewing to understand its scope and possible impact on rail service and network fluidity. While the STB did not perform a cost-benefit analysis, any new regulation must be backed by data, narrowly tailored to address a specific and well-defined problem, and ensure benefits exceed costs. Any switching regulation must avoid upending the fundamental economics and operations of an industry critical to the national economy—that Congress saved once by partially deregulating—and be subject to the highest level of scrutiny. AAR looks forward to engaging with the Board on this important matter.”

The American Chemistry Council (ACC) on Sept. 7 provided this statement from Senior Director of Regulatory and Scientific Affairs Jeff Sloan: “Removing regulatory barriers to competition through reciprocal switching is one of the most important changes the STB can make to improve rail service and help prevent future problems. While it’s disappointing that the Board is abandoning reciprocal switching as a mechanism to more broadly promote competition, we are hopeful that the revised proposal can offer meaningful relief to shippers when a railroad fails to meet objective service standards. We welcome the opportunity to work with the Board on finalizing this long overdue reform.”

Background

STB first proposed reciprocal switching regulations in 2016, following The National Industrial Transportation League’s (NITL) petition for rulemaking submitted in July 2011. A 2021 Executive Order on competition encouraged STB to review them.

The STB’s newly released NPRM explained the current framework for alternate access through reciprocal switching: “Alternate access generally refers to the ability of a shipper or receiver or an alternate railroad to use the facilities or services of an incumbent railroad to extend the reach of the services provided by the alternate railroad. The provisions of 49 U.S.C. §§ 11102 and 10705 make three alternate access remedies available to shippers/receivers and carriers: the prescription of terminal trackage rights, the prescription of reciprocal switching agreements, and the establishment of through routes … [R]eciprocal switching agreements provide for the transfer of a rail shipment between Class I rail carriers or their affiliated companies within the terminal area in which the shipment begins or ends its journey on the rail system. The incumbent rail carrier either (1) moves the shipment from the point of origin in the terminal area to a local yard, where an alternate carrier picks up the shipment to provide the line haul; or (2) picks up the shipment at a local yard where an alternate carrier placed the shipment after providing the line haul, for movement to the final destination in the terminal area. The alternate carrier might pay the incumbent carrier a fee for providing that service. The fee is often incorporated in some manner into the alternate carrier’s total rate to the shipper. A reciprocal switching agreement thus enables an alternate carrier to offer its own single-line rate or joint-line through rate for line-haul service, even if the alternate carrier’s lines do not physically reach the shipper’s/receiver’s facility …

“A reciprocal switching agreement can be voluntary or may be prescribed by the Board as provided in § 11102(c). Section 11102(c) authorizes the Board to require rail carriers to enter into reciprocal switching agreements when practicable and in the public interest or when necessary to establish competitive rail service … Currently, the Board has two sets of regulations under which it considers whether to prescribe a reciprocal switching agreement in non-emergency situations.

“Part 1147 of the Board’s current regulations addresses reciprocal switching related to inadequate service. Under part 1147, the Board will prescribe a reciprocal switching agreement (or terminal trackage rights under § 11102(a) or a through route under § 10705) if the Board determines that there has been a substantial, measurable deterioration or other demonstrated inadequacy in rail service by the incumbent carrier. 49 C.F.R. § 1147.1(a). Part 1144 governs reciprocal switching to address a broader set of issues, including certain types of complaints about pricing and/or service. Under part 1144, the Board will prescribe a reciprocal switching agreement or through route as necessary to remedy or prevent an act that is contrary to the competition policies in 49 U.S.C. § 10101 or is otherwise anticompetitive, provided that certain other conditions are also met. 49 C.F.R. § 1144.2(a)(1); 49 U.S.C. § 10101.”

STB’s Oberman noted in his Sept. 7 statement that “[s]ince joining the STB nearly five years ago, it has become apparent to me that many of the ills of the national freight rail network stem from a lack of competition in the industry and the fact that many rail customers are captive to one Class I railroad.

“In my view, Congress provided the Board with authority to issue reciprocal switching orders as one way to inject competitive alternatives into the rail network.

“Nevertheless, despite the consolidation of the number of Class I carriers from approximately 40 prior to 1980 to the current six Class I’s, no rail customer has succeeded in obtaining a reciprocal switching order in the last 40 years. Indeed, because of what are perceived as insurmountable hurdles by the shipping community under the current regulatory structure, no rail customer has even sought a reciprocal switching order from the Board since before 1990.

“Since at least 2010, the Board has been considering various ideas to reform the current reciprocal switching regulations so that captive shippers, in particular, would have a practical and realistic opportunity to obtain a reciprocal switching order when warranted. Unfortunately, until now, the Board has not developed such a reform.”

Frank N. Wilner Perspective

Railway Age asked Frank N. Wilner, Capitol Hill Contributing Editor and author of the just published “Railroads & Economic Regulation,” for his take on the NPRM. “Remarkable is the obstinacy of the STB to conclude a rulemaking languishing since 2011—yes, a dozen years ago, through a multitude of Board member changes, and mindful of a 1977 Business Week magazine observation of STB predecessor Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) as ‘an agency so soporific, so hideously encrusted with tradition, so hopelessly bereft of initiative that even the houseflies that wander in forget how to buzz,” Wilner said.

“In fact, it was 1998—a quarter century ago—that the Senate Commerce Committee urged the ICC to open a proceeding on rail access and competition issues. Then-Chairperson Linda J. Morgan was the first of multiple agency chairpersons to vacillate, responding that the issue is ‘more appropriately resolved by Congress.’ Thirteen years later, in 2011, STB Chairperson Daniel R. Elliott III, observing that the rail industry had ‘changed in many significant ways,’ opened a rulemaking to accomplish what Congress authorized rail regulators to do in 1980 and which the Senate Commerce Committee urged in 1998.

“With dead houseflies accumulating, the STB proposed in 2016—as suggested by the National Industrial Transportation League—that access issues be handled on a case-by-case basis, with Board member Ann D. Begeman (later chairperson) objecting it could introduce ‘more unpredictability’ in rail operations. As the rulemaking marinated into 2021, President Biden issued an Executive Order encouraging the STB to do its job, earn its keep and complete the rulemaking. Chairperson Martin J. Oberman said he welcomed the challenge.

“That challenge was met Sept. 7, 2023, with the Board dispatching the rotting carcass of the original rulemaking, Ex Parte No. 711 (Sub No. 1) to curbside trash and opening a new docket, Ex Parte No. 711 (Sub No. 2). Now proposed is to limit the access issue to service-related events—at, perhaps, the expense of competition-related events. Who, but railroads, could love this regulatory agency? Wasn’t its predecessor declared by a shipper in 1984 to be a ‘wholly owned subsidiary’ of the Association of American Railroads? As the AAR said in its prepared statement responding to the Sept. 7 STB decision, it’s ‘a positive development.’

“From inside the Board came a confidential remark, ‘There is an expedited comment period and five votes consensus. We are going to get it done very soon.’

“Not to be a nattering nabob of negativism, but some may recall ICC Chairperson Reese H. Taylor Jr., who earned a Ronald Reagan 1985 demotion as Chairperson for his failure to move the Board toward action. Taylor’s reference to two deep-sea divers—‘Mike and Ike’—who might suffer the bends were they brought to the surface too soon was more than Regan could stomach as an excuse for not hastening the Republican rail deregulation agenda after the concept had won bipartisan congressional support five years earlier.”

TD Cowen Commentary, by Wall Street Contributing Editor Jason Seidl

The STB issued a framework for a new proposed rule on reciprocal switching as we had anticipated would occur in 2H23. The new proposed rule departs significantly from the foundations of the 2016 rule and in our view, narrows the scope of switching eligibility while streamlining enforceability.

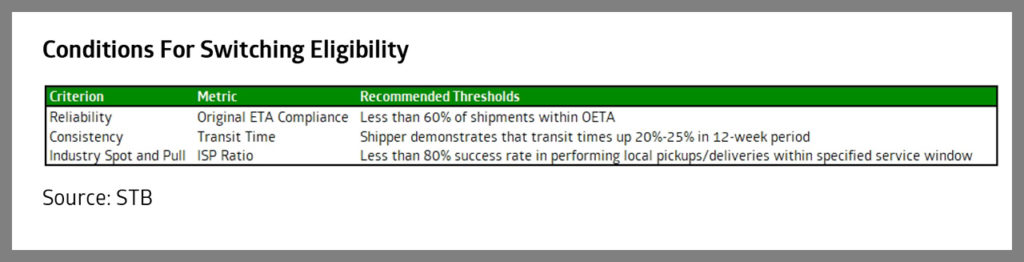

The new rules establish service metrics as criteria determining eligibility for a switch and narrow eligibility for the remedy compared to 2016 rules. Tentatively, under the new rule, a shipper with practical physical access to only one Class I would be eligible for a switch away from the incumbent based on one of three service criteria, including trip plan compliance (on time percentage), transit times and local service:

The Public Interest Pathway under the 2016 rules covered roughly one-third of Class I carloads per our estimates and was notably broad in scope compared to these new rules.

In our view, the STB’s thresholds are somewhat lenient to Class I’s. We view this as not being nearly as bad as it could have for the group. When Class I’s reported respective service metrics to the STB in May 2022 (near the peak of volumes), all the reporting Class I’s had trip plan compliance exceeding 60%, and only one had ISP ratio below 80%. CSX and Union Pacific show slightly different forms of trip compliance on a quarterly basis (CSX shows total carloads and UP shows Manifest/Autos), both of which historically been above the 60% threshold, though they dipped below in 2021 and 2022. In 2Q23, both railroads met the threshold.

The STB also suggested that the 60% estimated time of arrival would increase to 70% after a year; this would give the railroads more time to hire and train employees in order to meet that threshold. CSX and UP had been above this threshold YTD and in 1Q20 leading up to COVID, though we do note that these compliance numbers are averages, and some shippers could experience below-threshold levels.

In addition to lenient service thresholds, the new rules propose a limited term for switching. The STB will grant switching accessibility for 2 years and in some cases up to 4 years, following which the Class I will have a chance to seek termination of the arrangement if service criteria are met. The proposed switching regime in the U.S. is a far cry from the accessibility that applies in Canadian interswitching, where uptake of switching is low to begin with.

With the STB intent on establishing more easily quantifiable eligibility criteria, application of the rules when suitable should be easier. Under 2016 rules, the shipper bore the burden of proving anticompetitive behavior, a notoriously high hurdle to pass per shippers. We agree with the STB’s contention that legal hurdles to accessing the rules when eligible should be reduced under these new stipulations.

The new rules are subject to change following comments from stakeholders. Shippers are likely to request more favorable thresholds for eligibility to switching remedy. Replies to comments are due Nov 21. The Association of American Railroads (AAR) has voiced support for scrapping of the 2016 rules but is yet to opine on the new proposal. We believe the Class I’s will find some comfort in the new rules relative to 2016 rules.

We await comments within the industry regarding switching and continue will monitor the situation. Additionally, the FRA is still taking comments on train weight and length, which close on Sept. 19.

Loop Capital Perspective, by Rick Paterson

This is going to set off a giant food fight between the STB and the railroads, but do investors need to worry about it? In our view, the answer is no, for several reasons:

- Adding a reciprocal switch will often delay main line departure for a day, so unless the non-incumbent railroad has a route that’s a day shorter, there’s a natural transit time incentive for the customer to stay with the incumbent railroad.

- The STB has reasonably narrow guidelines in terms of the areas where reciprocal switches can take place. This isn’t a wide net.

- The STB is developing service standards below which the incumbent carrier would have to fall for an extended period before the customer is eligible for a reciprocal switch. These may start as low as 60% manifest on-time performance and 80% first-mile, last-mile.

The plan is to raise these standards over time, which builds in a regulatory incentive for service to improve (which of course we like). Bottom line: If you’re invested in a railroad that can’t navigate these proposed new rules and loses material amounts of business as a result, you’re probably invested in the wrong one, and it’s time to reciprocally switch your investment.

What Would Hunter Say?

The late Hunter Harrison was Railway Age’s 2015 Railroader of the while President and CEO of Canadian Pacific (now CPKC). Editor-in-Chief William C. Vantuono asked Harrison his opinion of open access and reciprocal switching:

VANTUONO: The regulatory situation in Canada is a bit different than in the US. There is some form of open access, to a very limited extent, and you don’t seem to have a problem with that. Some of the U.S. railroads are fighting that tooth and nail. What’s the difference? How’s it work?

HARRISON: It’s called inter-switching, which relates to some degree to the U.S.’s old reciprocal switching, pre-Staggers. It’s one of these regs that are in place, but people don’t really take advantage of it, because there’s no need to if the individual carriers do their job. It’s kind of something that could be called a lever that you have over here, if it needed to be used. My view is, for years a lot of railroaders had been scared of the term “open-access,” and I don’t know why. What that says to me is, all we’re going to do is open up more competition, and with a very limited number of players in North America now, it’s important to keep that competitive balance. And if an individual carrier, CP included, provides the right type of service for the customer, at an appropriate fair price, we have nothing to worry about. If we do not provide the service, we should not be resistant to someone [else] coming and providing that service. So I think it’s different, it’s change, and people, generally speaking, their normal reaction is to resist those initial change efforts. But I think if we would look back here in 20 years, most of these things are going to be behind us, and we’re going to be settled down with those types of issues.

Further Reading

A Primer on Reciprocal Switching

Oberman: STB Remains Actively Involved in Rail Reg Mods

Does the AAR Fear Competition?

DOJ Weighs in on Reciprocal Switching

AAR to STB: Reciprocal Switching a ‘Wealth Transfer to More-Profitable Entities’

Reciprocal Switching’s Potential Impact on Passenger Rail (UPDATED)

NS, STB Talk ‘Reciprocal Switching’

Will STB Take Up Reciprocal Switching?

Reciprocal Switching: Complex, Expensive, Time-Consuming (i.e. Mostly a Bad Idea)

UPS to STB: Forced access forces us off the rails