Ending a 50-Year Embargo in the FRA Amtrak Long-Distance Study

Written by William C. Vantuono, Editor-in-Chief

Amtrak photo

Netting out Formulaic Leveraged Highway Funding Effects in a BCA

ALLRAIL EU | Nick Brooks

Benefits from lower fares and higher quality service (1) are arriving in European democracies for passengers and all operators through intra-modal rail competition. In Europe we have advocated for modal equalization, because unfortunately aviation fuel is not taxed (2; 3) — whereas inter-country rail tickets are – and where rail operators absorb accident costs, yet highway accidents are public costs. Politically, pushing for say pricier airline tickets is unlikely. Thus, a second-best competitive market policy is an equivalent level of public investment in railroad infrastructure earned by train-mile (4) actually operated, equally useful for all passenger train operators on equal terms, atop relatively fixed funds for commuter area infrastructure.

My travel in the United States leads me to conclude these same benefits can be had here for travelers on 200-to-1000-mile mid-distance trips without replacing the shareholder owned integrated railroad freight franchises or the National Railroad Passenger Corporation (NRPC) dba Amtrak, but rather with a public partnership with each doing what they are best suited to do for an enhanced overall rail network.

For passenger rail, it seems the United States has long sought to fund only capital costs, be it either vehicles or infrastructure, yet a fungible mix of capital and operational improvements delivers a lower average cost. Federal investment should first flow to Below-the-Rail Infrastructure Operations by train-mile, funding mainlines, terminals, boarding platforms, security planning, and risk coverage, but through the existing contracts and owners under a Public Private Partnership (P3). Then the passenger Vehicle Operator, selected under a P3, could nimbly provide vehicles, maintenance, consumables, and staffing, everything Above-the-Rail, largely from consumer responsive revenue and locality sponsorship.

With this restructuring, long-distance service can grow, as seen in parts of Europe, without changing existing infrastructure ownership but rather by incentivizing the overall network performance in a US context as detailed next.

U.S. Surface Transportation Program (STP) Renewal | Virgil G. Payne, PE

In the United States, highway funding programs consider benefits to freight and persons, yet oddly federal intercity rail programs often try to separate the two uses of the same infrastructure, why?

The last major United States Department of Transportation (USDOT) Amtrak route reevaluation has an interesting side story, starting in 1973 department critiques that cast Amtrak as inefficient relative to Interstate Highways. Congress eventually passed legislation clarifying the public service mission of Amtrak and requested a study. The Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) conducted public meetings, identified benefits to keeping the routes, and published a 1978 report (5). But the USDOT still released their final 1979 report (6) with criteria largely premised on rail passengers paying for both vehicles and infrastructure, a position unique amongst other modes. The root of this same misunderstanding, that the leveraged gas taxes are said to incrementally pay for highway capital, is seen in guidance to this day.

How, one asks, modern era Benefit to Cost Analysis (BCA) methods are supposed to evaluate past and future public funding for transportation projects to select for true resource efficiency? Unfortunately, USDOT policy lacks a nationwide metric for Highway Trust Fund (HTF) formulaic financing that never passes through a modern BCA economic evaluation gate. This is a large effect as the HTF leverages fuel taxes, collected during the use of an almost fifteen-times larger preexisting base of locally funded streets and county roads, towards intercity highway projects, as shown in by a financial analysis of six-decades of Interstate Highway records (7). When these financial flows fund projects at rates not subject to a BCA throttle, they enable the depression of the market price for transportation, leaving intercity rail to charge less in a competitive marketplace, thus inducing Net losses from depressed Ticket Revenue and higher Operating and Maintenance unit costs when less capacity is produced.

Benefits in the BCA process are meant to distinguish specifics of alternatives, not correct for imbalances in programmatic modal funding. For nearly 50 years USDOT guidance has taken that user fees incrementally pay for rural Interstate Highway capacity capital, ignoring that the HTF was specifically set up to leverage when a nationwide toll highway program to fund capital was determined unworkable (8).

Correcting for HTF Leverage with a Simple BCA Metric

This 50-year USDOT embargo by guidance, where grants for capital and maintenance of existing intercity railroad infrastructure are routed through a lengthy BCA grant approval process but highway 4R (9) funds are programmatically distributed, needs to be removed for both intercity freight and passenger rail infrastructure funding, or the ongoing USDOT/FRA Amtrak Long-Distance Study will likely face the same fate as the 1979 study.

It is up to the USDOT to revise the guidance upon which Congress relies, particularly the BCA Modal Diversion commentary on Price-Demand curves, were no nationwide highway net capital and maintenance deficit is noted. Instead it obliquely notes “the generalized costs for using the competing alternatives from which an improved facility draws additional users are already incorporated in the demand curve for the improved facility or service.” (10) But if incremental user fees were increased to eliminate the net capacity financial cost, the demand for highway travel would decline, as has been seen when gasoline prices spike, affecting economic models. As highway projects suppress the market clearing freight and passenger price, pure toll highways for congestion management become nearly impossible except at bottlenecks. The simplest nationwide solution, absent a true market price, is to include a highway incremental financial cost reduction benefit in rail project BCA economic models.

In the Appendix’s worked example this leveraged fuel tax capacity BCA metric is termed Highway Net Incremental Capital and O&M (11). While this figure does include pavement damage incorporated in some BCA models, its largest component is a capital repayment deficit, the financial net between incremental taxes and fees collected by governments and the long-run infrastructure costs over the last six decades for Interstate Highways. If both Interstate Highway and Railway projects used the incremental cost of dealing with a future capacity constrained state (12) the BCA economic tools could find the most innovative project in terms of safety, emissions, and energy use and crucially forge a plan to improve both types of infrastructure in parallel instead of picking one project or the other.

A Public Private Partnership (P3): Passenger Service Development Plan (SDP)

This BCA talk is all rather academic unless one wants stable communities and centers of commerce throughout the interior of the nation. Intercity rail seems to do this best, whereas highways seem best at simply expanding already large centers further. The community shaping function of a relatively small leading public investment is substantial, but a nimble consumer revenue dependent operator is needed.

Improved governance can be had with a P3 by reforming the current financial structure lacking ownership. From long ago ICC templates, the long-distance passenger rail routes are assigned as expense, thought to need offsetting consumer revenue, what is really infrastructure cost for shared mainlines, terminals, platforms, and risk. Labeling these as operational costs on National routes but capital costs elsewhere lead to confused commercial decisions. While this article focuses on the General Railway System, the same principles could be used for newly constructed high(er) speed passenger mainlines since the metrics are derived relative to the nationwide highway influenced market.

Combing the proposed Highway Net Incremental Capital and O&M metric to normalize for highway leveraging with a business decision to follow the declining Average Cost Curve as volume grows when infrastructure operators and vehicle operators are segmented, increases intercity rail BCA ratios from around 1.1 to about 3.8 as seen in the Appendix Sketch-level SDP.

Intermodal Freight Infrastructure Investment – Complemented by Parcel Express

The P3 route funding structure would also provide a public Below-the-Rail investment for infrastructure for intermodal freight trains, to offset the same highway trust fund leveraging affecting passenger train revenue and steer the mainline design and operations toward fluidity. These investments would not be tied to a particular intermodal terminal site as in previous grants or technology, but rather would allow for market adjustments to occur over time. Thus, host railroads might not consider that higher speed express on passenger trains is diverting business, but instead merely price-segmenting the intermodal freight product while expanding the overall market volume as an entrance gateway.

Previous passenger train express operations were undercapitalized, as they were relied upon to minimize overall public funding, so efficient mechanized loading techniques lagged. For the purposes of the SDP a semi-automated pallet shuttle concept is explored, aiding the unloading of express railcars while providing pallet based checked baggage service. Alternately, loading standard 53-foot box trailers, which are around twelve times more common than containers, with a new semi-automated transfer into low center of gravity intermodal well cars good for 90 MPH service would generate net revenue for passenger operations while creating a tool for host railroads to cooperatively expedite a particular container load on its chassis to meet a freight customer’s needs.

Details of the Proposed P3 Governance and Financial Structure

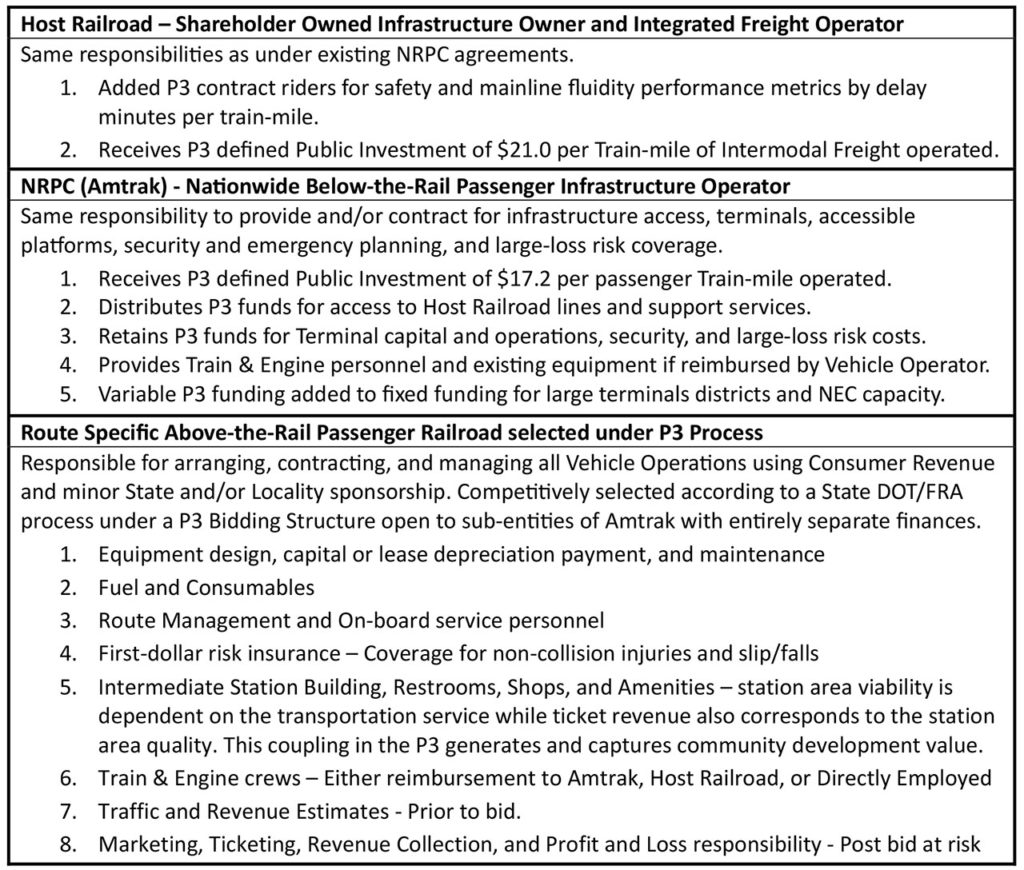

Alternative business reporting at Amtrak could start tomorrow, but the identified BCA revisions and broad intermodal freight investments for mainline fluidity are needed for a nationwide solution. A legislative separation of passenger rail infrastructure and vehicle operations into distinct entities as in Figure 1 for a P3 grant with entirely separate finances and governance structures mirroring highway and aviation modes, or through a nationwide Tax Credit (13), would provide structure for long-term growth.

Passenger Vehicle Procurement Flexibility

Absent sufficient revenue from different passenger accommodation tiers and express, a long-distance passenger train can be like a 4-engine regional jet, with high fixed costs and skimpy revenue per mile. How could the P3 structure hasten vehicle delivery to develop the capacity for these revenue streams?

Since the federal and state governments would not be leading the procurement or funding vehicles there should be a minimal review, comprised of ascertaining if the design is according to FRA performance regulations. With the P3 vehicle operator contributing 10% of junior equity toward the purchase or refurbishment of the vehicles, they would stand to lose the most, which should guarantee any federal interest in a RRIF loan to cover the remainder of the purchase. The overall P3 grant structure could also justify a 10% Buy America content waiver and provide a vehicle buy back option at the P3 term end to satisfy the RRIF loan remainder, yielding a functional vehicle mini-marketplace as in the EU.

Establishing a Revenue and Service Quality Feedback Loop

This vehicle procurement flexibility is vital, as the interior quality and the amenities provided to a consumer can change the perception of time, increasing Time-Utility through mobile work and rest but the cost must be linked to revenue and the preferred trip time of day must be considered by methods other than aggregate Origin-Destination trip counts. Such a Time-Utility Ridership Model issupported by a P3 grouping of vehicle capital and operations, crucial to business success as a seat alone will not serve “People traveling for pleasure, or combining business and leisure, known in the industry as “bleisure,”… in some cases spending as much as or more than the pre-pandemic corporate road warriors.” (14)

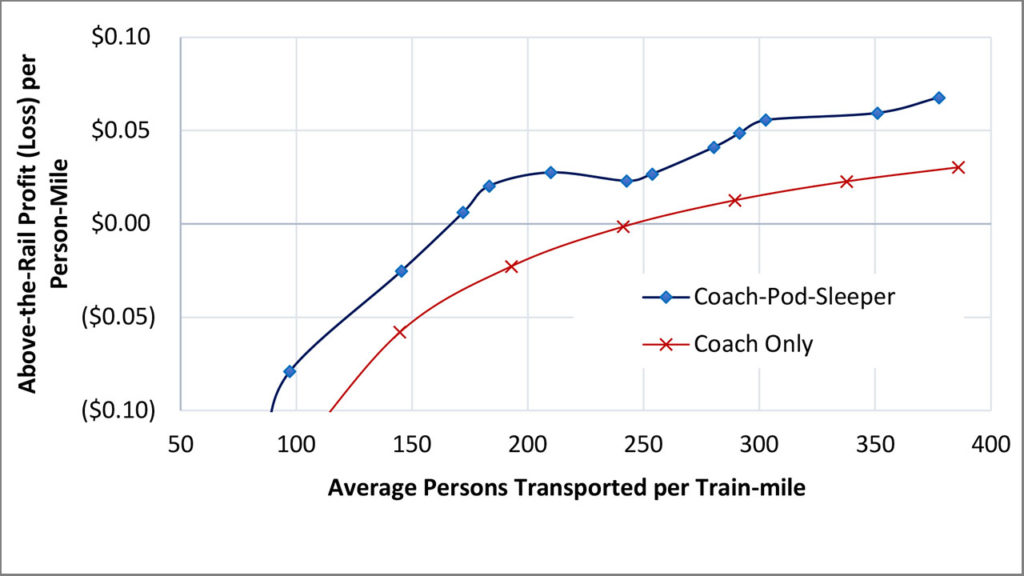

This is essentially the reason many prefer a large SUV for a long highway trip, the greater in-cabin quality. This reality-based revenue model would also lead to enhanced food and beverage service and a mix of coach, flat-pod beds, and private sleeper accommodations for travelers. Most importantly, by combining service levels in each train, many more rural routes are profitable Above-the-Rail at lower volumes.

Previous Passenger Rail Reform Attempts

There have been previous Congressional directives to study passenger rail reform. One proceeded without recognizing the need for public infrastructure investment, limiting reforms to organizational structure changes (15). Twenty years ago, the Amtrak Reform Council rightly noted the need to separate Northeast Corridor (NEC) infrastructure operations and vehicle operations (16) but did not address the rest of the nation’s infrastructure funding or a rationale for public mainline capacity investment relative to highway expenditures. This proposal recognizes this infrastructure funding oversight as the most critical element and includes public funds for the average cost of mainline capacity, benefiting freight and persons, with a performance metric aimed at bettering the mainline delay threshold for all traffic.

Suggested Next Steps in the FRA Amtrak Daily Long-Distance Study

The three key elements identified need to be considered in the next phase of the FRA Amtrak Daily Long-Distance Study for it to produce the full range of policy guidance that Congress requested. The use of parametric values could allow this work to occur in just a few months.

- Highway Net Incremental Capital and O&M – Establishment of a nationwide basis for correcting the market price-demand curves in Benefit to Cost Analysis calculations for highway fund financial leveraging resulting from HTF funds that never pass through a BCA grant gate.

- P3 Financial and Performance Metrics – Enacting grant guidance for distributing funding by enhanced Intermodal Freight and Passenger train-mile operated atop existing fixed commuter district funding.

- Time-Utility Ridership Model – Encouraging ridership modelers to explore real-world factors like the quality of the user’s experience instead of disproven time-saved wage rate analysis.

Developing these concepts beyond the sketch-level SDP to the point where bids could be taken is needed as Congress considers legislation to illustrate how funding metrics can support truly resource efficient industrial development and community resiliency benefits across the interior of the United States. The criteria for selecting long-distance passenger routes are consumer revenue covering Above-the-Rail cost under state sponsorship if the federal government pays for the Below-the-Rail infrastructure and risk, simple. Perhaps enough experience has been gained for these changes to make it into legislation as the price of doing the same thing is getting too high (17) when a competitive P3 could bring benefits in an accelerated timeframe by moving from a series decade-plus approval process to a parallel implementation program of a few years.

Appendix: P3 Sketch-level Development Plan (SDP) – Worked Example

North Coast Hiawatha Reinstatement – A 2,250-mile, two-night long-distance route from Chicago to the West Coast, serving rural transportation needs, intermediate metro areas, and national parks with support for intermodal freight infrastructure investment. This route was selected as one of the most challenging to implement to demonstrate how the suggested next steps in the FRA study would work in more detail.

Biographies

Nick Brooks has a background in trying to make passenger rail more competitive. Previously, he was Head of EU Affairs at the online rail ticket retail platform Trainline. Prior to that, he spent several years as Head of Sales & Business Development at the startup long distance passenger rail operator Hamburg-Cologne Express (‘HKX’) in Germany. Nick gained his first experience in competitive public transport by working for the low-cost airline Frontier Airlines in Denver, USA. He has an MBA from Purdue University and an MSc Finance from Colorado University in Denver.

Virgil G. Payne is a professional engineer supporting industry—where fixed and variable cost functions must be understood—reliant on both highway and railway logistics. Previously he supported his state DOT coordinating mostly highway projects, such as I-269 from planning to construction. This work followed a period of designing infill buildings, sites, and utilities and a brief stint in railroad operations, yielding a perspective from both sides of the fence on customer needs and transportation projects. The position taken is entirely his own as a call to begin talking consistently about financial costs to reform the surface transportation system design and funding mechanism for true resource efficiency.

References and Notes:

2. European Commission. Transport taxes and charges in Europe. s.l. : European Commission, 2019.

4. Brooks, Nick. ALLRAIL Vision For Night Trains. Brussels: ALLRAIL EU, February 2020.

7. Payne, Virgil G. Reforming Surface Transportation for Long-Term Sustainability. Washington, DC : Competitive Enterprise Institute (CEI), Issue Analysis 2020 No. 10, November 2020.

9. Ironically, the Highway 4-R act involved the beginning of federal funding for maintenance of Interstate Highways previously only given capital grants and substantial resurfacing, restoration, rehabilitation and reconstruction of existing highways, while the railway 4-R act involved a plan to downsize the eastern mainlines so the remaining traffic under Conrail could cover both the long-run capital requirements and maintenance from freight revenue without public investment while placing the commuter mainlines under Amtrak’s public expense bracket.

11. Highway Net Incremental Capital and O&M is calculated nationwide from six decades of Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) Interstate Highway records to be $0.109 per automobile mile traveled and $0.26 per Class 8 combination truck mile traveled up until 2018 using toll road prorations for capital assignment. The value is expected to be higher when recalculated for the recent increasingly large general fund transfers to the HTF. It is the amount estimated to come from taxes outside the ramps of the Interstate system. To back-check, consider that research sponsored by the Texas Department of Transportation recommended a minimum test toll of $0.12 per automobile vehicle-mile in 2004 ($0.16 per vehicle-mile in 2018 dollars) for revenue and traffic studies to see if tolling could pay for conceptual projects but the average State and Federal fuel tax is less than $0.02 per automobile mile traveled. Marginal fuel tax revenue generated on un-tolled new highways was found to equal only about 10 percent to 20 percent of the construction and maintenance costs net of vehicle registration taxes that do not vary with VMT. However, many toll road projects cannot charge this amount, as it would result in little traffic. Instead, they now only charge what can be borne by the marketplace and floated with low-interest loans, before dipping into the trust fund for the rest. While many of these are high-occupancy toll lanes, the policy challenge lies in the current inability of politically acceptable tolls or gas taxes to fund the full costs of many facilities.

12. The suggestion is not to stop all highway expansion, allowing for congestion to raise the market clearing price for alternatives is not a very likely long-run solution politically. Only by understanding HTF leveraging can better governance of the STP be had with the growing gap between USDOT discretionary grants and the trust funded programs for both Interstate Highway and Railway projects. MEGA grants, even if won, are only providing around 1/3 of typical highway capacity funding. Instead, the Highway Net Incremental Capital and O&M could be used in the BCA as a rationale for rebuilding highways instead of claiming to incrementally reduce the large existing costs of accidents or congestion. A similar justification should be afforded intercity rail to incrementally reduce the large existing baked-in costs of ongoing Highway Net Incremental Capital and O&M, otherwise Rail projects applying for grants with a typical BCA are working against a nonsensical highway demand curve.

13. Payne, Virgil G. Renewed Consumer Relevance of the General Railway System. Railway Age. 2021.

17. Wilner, Frank N. A Failure of Public Enterprise? Railway Age. [Online] November 2018.

19. Vadali, Sharada, et al. Guide for Conducting Benefit-Cost Analyses of Multimodal, Multijurisdictional Freight Corridor Investments. Washington DC : National Academy of Sciences, 2017. NCFRP RESEARCH REPORT 38.