Pre-Pandemic Rail Is a Thing of the Past

Written by David Nahass, Financial Editor

David Nahass, Railway Age Financial Editor

FINANCIAL EDGE, RAILWAY AGE FEBRUARY 2024 ISSUE: Only those people who are capable of being a soulless rake (a rake is a person prone to excess) leading a careless and superfluous life can avoid concerning themselves with mundane issues of the working world such as measuring productivity. For the rest of the population, including the parties involved in the rising (and occasionally falling) fortunes of the North American rail market, data matters.

Railway Age reported that in the Jan. 18, 2024 Federal Register, the STB issued its annual five-year rail industry productivity calculation. Railroad productivity is, in essence, how efficiently railroads move freight. The rail productivity measure is a five-year backwards looking window. This being early 2024, the data for 2023 is not used in this calculation.

The STB reported a slight drop of 1.5% in the five-year measure. The decrease was expected or at least unsurprising, considering the challenges to and outward facing perspective on railroad service that have been a recent focus.

These productivity number levels are not surprising. Non-farm productivity (tracked by the Bureau of Labor Statistics) rose 1.5% in the timeframe of 2019 to 2023, so almost 30% more than rail but not in an absurdly eyepopping way.

What makes rail productivity so interesting? Start with a few basic facts. For calendar year 2018 (ending Dec. 29, 2018), total U.S. loadings (including intermodal) were 28.11 million. 2018 was a banner year for rail loadings. The 2018 total is a 3.7% increase over 2017. Fast forward to 2022. For calendar year 2022 (ending Dec. 31, 2022), total U.S. loadings were 25.4 million. That’s a decrease of 9.6% (2.7 million loads). In 2018, July Class I employment was roughly 147,700. In November 2022, the number was 118,944. That’s a 19% difference. More interesting is that the 2022 number is roughly around where employment was in May 2020, when the pandemic caused significant layoffs.

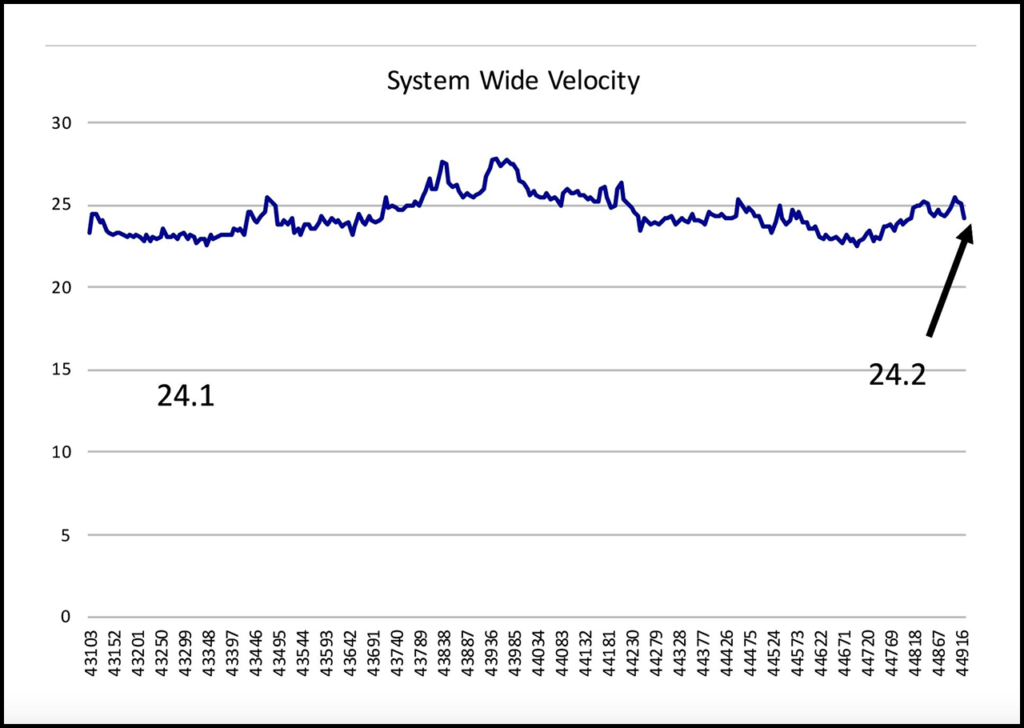

Need some more information? Systemwide (again U.S.) velocity on Class I railroads in the early part of 2018 is roughly the same velocity as the railroads were operating at the end of 2022 (approximately 24 mph, see the chart below).

Perhaps the most interesting factoid spanning that period is what the STB calls “Adjusted Net Railway Operating Income.” This is a measure used in determining Railroad Revenue Adequacy. For the year ending 2018, that number was (across all Class I U.S. operations) US$19.77 billion, and in 2022 it was US$23.67 billion. That is an increase of 16.5%.

One key difference between general non-farm productivity and rail productivity is that U.S. GDP increases pretty much every year. It means that the U.S. economy is always growing. It is the pace of growth that matters and impacts daily lives. Even in the pandemic year of 2020 after an incredible economic contraction, the U.S. economy still managed to squeak out a full year expansion.

Not exactly so with the rail economy. To summarize: Loadings have decreased, velocity is the same, the industry employs significantly fewer people and income is way up. Yet through all of this, productivity over the time frame has actually decreased. Now—you decide—is the rail economy expanding or contracting?

Rail productivity goes into calculating rail rate reasonableness. Certainly, a decrease this modest will not have an outsized impact on what rail rates will look like in the coming year.

While this data set is not complete, it suggests one very clear thing: Moving freight by rail was more expensive in 2022, and the railroads made more money moving freight in 2022 than in 2018. They moved less freight with fewer people at roughly the same speed. Sounds like a great business model. It’s almost as if the roughly 25% reduction in coal traffic over that period was actually better for the railroads.

The ongoing cogitation around railroad industry growth obscures a fact hiding in plain sight: Railroad growth is the problem. Finding growth that supports the same margins and increased income levels seems to have put a ceiling on loadings.

In 2023 there was a true 10% reduction in grain and a 5% reduction in forest products loadings. Gravitation to the nominal mean for those commodity classes still would not bring loadings back to 2018 levels. But such a bounce back would suggest more railroad income.

Shippers and suppliers waiting for a volumetric related increase in loads and decreases in pricing should read the writing in the Federal Register and realize that pre-pandemic rail is, well, a thing of the past. Maybe being a soulless rake isn’t such a bad idea after all.

Got questions? Set them free at [email protected].