Court Halts Uinta Basin Railway Project

Written by Marybeth Luczak, Executive Editor

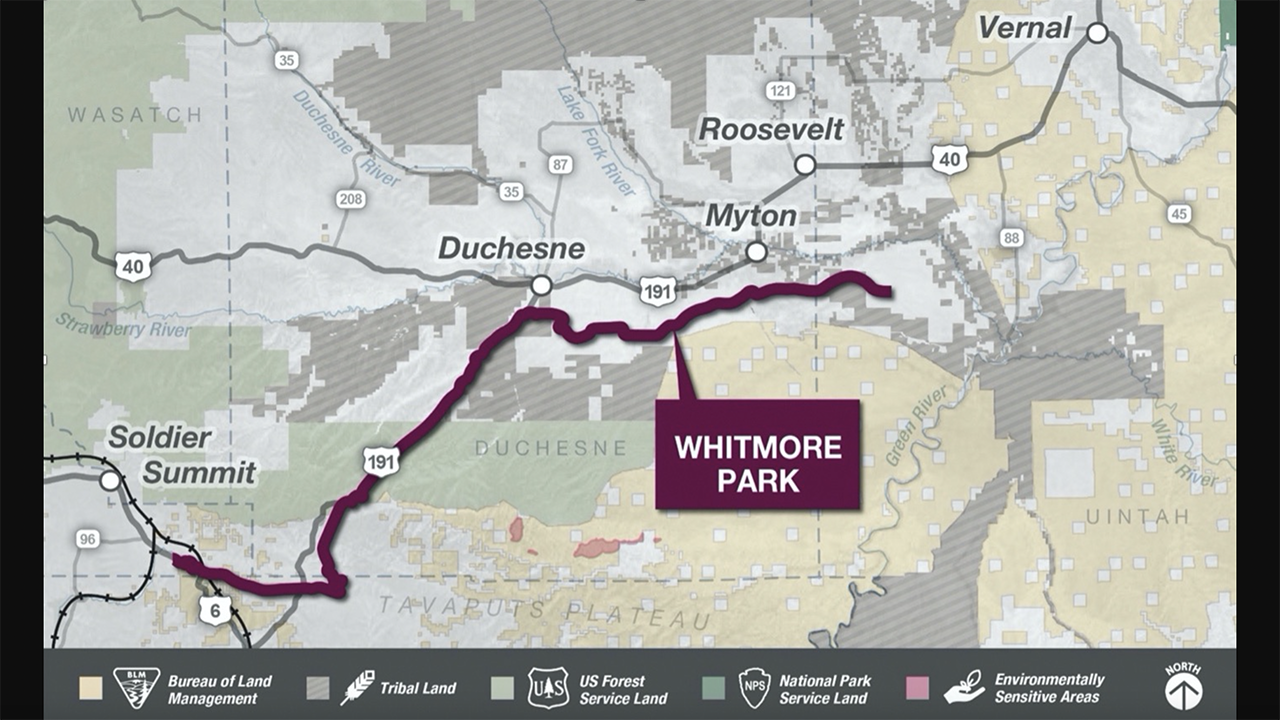

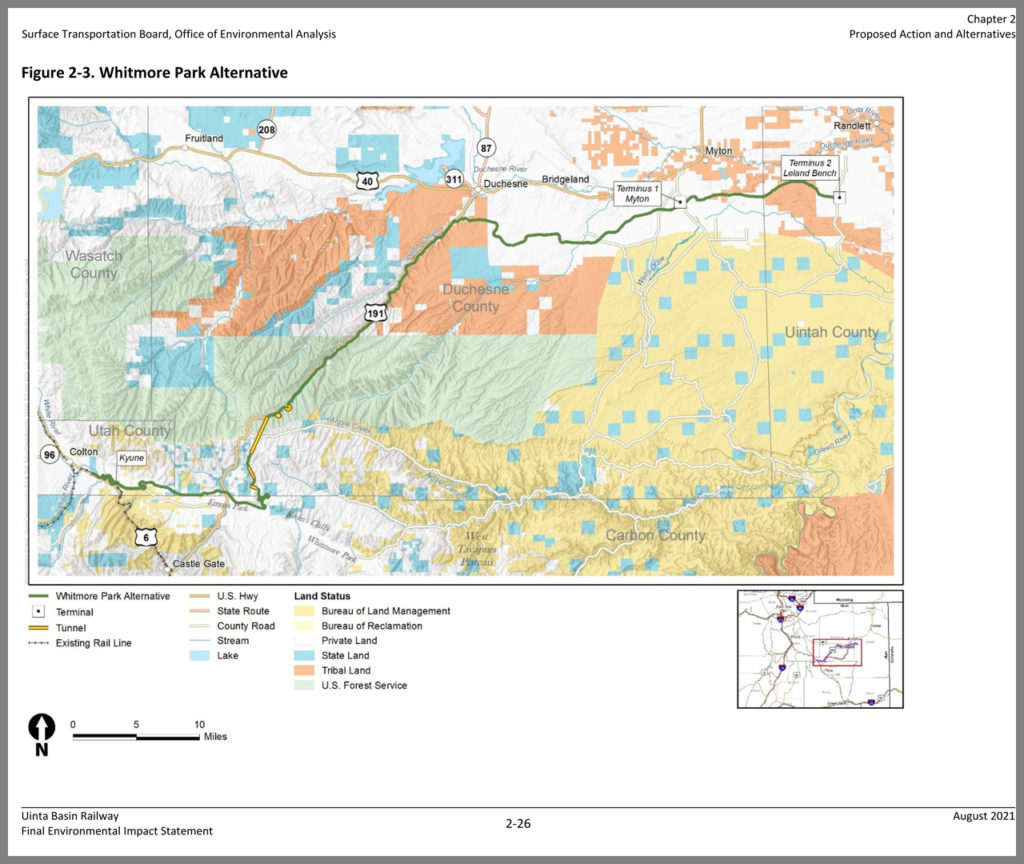

In August 2021, the STB Office of Environmental Analysis issued a Final EIS for the project, identifying the 88-mile Whitmore Park Alternative as the environmentally preferred route for the Uinta Basin Railway, one of three analyzed. It would extend from two terminus points in northeastern Utah’s Uinta Basin near Myton and Leland Bench to a connection with the existing Union Pacific Provo Subdivision near Kyune (see map above).

The Surface Transportation Board’s (STB) December 2021 approval of the construction and operation of the Uinta Basin Railway was struck down by the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit, which called it “arbitrary and capricious.”

The 88-mile line would be the first major freight railroad built in the U.S. in the past 30 years. Behind the project is Utah’s Seven County Infrastructure Coalition, an “independent political subdivision” of the state that sought STB approval for the line, which would primarily haul shale-extracted crude oil. The Coalition joined forces with Drexel Hamilton Infrastructure Partners to raise private capital for the build and with Rio Grande Pacific Corp. to operate and maintain the line once completed. AECOM was chosen to lead the design, and the Skanska-Clyde Joint Venture and Obayashi Corporation would help with construction.

The court’s Aug. 18, 2023 decision (download below) granted in part the consolidated petitions of Eagle County, Colo., and the Center for Biological Diversity and vacated the STB’s final exemption order as “arbitrary and capricious.” It also vacated in part STB’s Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) outlining the various impacts associated with the railway’s construction and operation, and the Biological Opinion (BiOp) concerning the railway’s potential impacts on endangered species and critical habitats. The matter was remanded to STB for further proceedings.

The Court explained that the decision to vacate depends on two factors: “the likelihood that ‘deficiencies’ in an order [like STB’s] can be redressed on remand, even if the agency reaches the same result, and the ‘disruptive consequences’” of vacating.

According to the Court, “[T]he deficiencies here are significant. We have found numerous NEPA [National Environmental Policy Act] violations arising from the EIS, including the failures to: (1) quantify reasonably foreseeable upstream and downstream impacts on vegetation and special-status species of increased drilling in the Uinta Basin and increased oil-train traffic along the Union Pacific Line, as well as the effects of oil refining on environmental justice [of] communities [in] the Gulf Coast; (2) take a hard look at wildfire risk as well as impacts on water resources downline; and (3) explain the lack of available information on local accident risk in accordance with 40 C.F.R. § 1502.22(b) (2020). The EIS is further called into question since the BiOp failed to assess impacts on the Colorado River fishes downline.”

The Court wrote that “[t]he poor environmental review alone renders arbitrary the Board’s consideration of the relevant Rail Policies and the final order’s exemption of the Railway.” STB “also failed to conduct a reasoned application of the appropriate Rail Policies as required under the ICCT Act [Interstate Commerce Commission Termination Act of 1995],” according to the Court. It said STB “failed to weigh the Project’s uncertain financial viability and the full potential for environmental harm against the transportation benefits it identified.”

The “normal remedy” is to vacate a rule found to be unlawful, according to the Court, which wrote: “[W]e see no reason to depart from our normal practice here given the lack of argument from the Board, [BiOp producer the Fish and Wildlife] Service, or the [Seven County Infrastructure] Coalition, that vacatur would be disruptive.”

In an Aug. 18 Facebook post following the ruling, the Seven County Infrastructure Coalition said: “The #UintaBasinRailway team remains committed to the successful planning, construction, and operation of the railway. While we disagree with the D.C. Circuit Court’s recent decision, we respect the authority of the U.S. Court of Appeals. We firmly believe that the railway’s Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) contains appropriate and thorough analysis of the highlighted concerns, as it stands today. Nonetheless, we are ready, willing, and capable of working with the U.S. Surface Transportation Board to ensure additional reviews and the project’s next steps proceed without further delay. We look forward to bringing this railway to the Basin in a safe and cost-effective way to enable economic stability, sustainable communities and an enriched quality of life to Utahns and beyond.”

Sen. Mike Lee (R-Utah) released the following statement via social media platform X (formerly known as Twitter) on Aug. 18: “This blow against the Unita [sic] Basin project represents a missed opportunity for our communities to thrive. The National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) and the accompanying Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) for the project were both thorough and exhaustive in their valuations, so this decision is a needless setback for Utah. The Unita [sic] Basin Railway is not just about American energy: it’s about jobs, economic growth, and the prosperity of our great state. It is deeply concerning to see decisions that appear more influenced by ‘woke environmentalism’ rather than grounded, data-driven evaluations. This undermines the integrity of our regulatory process and stifles innovation. I will continue working with my Senate colleagues, our state’s leaders, and all relevant agencies to ensure this project moves forward promptly.”

Background: Uinta Basin Railway Project

On May 29, 2020, the Seven County Infrastructure Coalition sought STB authority to build and operate the Uinta Basin Railway, which it said would provide Basin shippers a viable alternative to trucking—currently the only available transportation option. The Uinta Basin is an approximately 12,000 square-mile area spanning northeastern Utah and northwestern Colorado that contains mineral deposits, including phosphate, crude oil, natural gas, oil shale, oil sands, gilsonite, natural asphalt, aggregate materials and low-sulfur coal.

STB on Jan. 5, 2021 preliminarily approved the project on its transportation merits, subject to completion of environmental review.

In August 2021, the STB Office of Environmental Analysis issued a Final EIS for the project, identifying the 88-mile Whitmore Park Alternative as the environmentally preferred route, one of three analyzed. It would extend from two terminus points in the Uinta Basin near Myton, Utah, and Leland Bench, Utah, to a connection with the existing Union Pacific Provo Subdivision near Kyune, Utah (see map below). The route includes five tunnels, totaling 5.7 miles. The estimated construction cost: approximately $1.35 billion.

“Depending on future market conditions, between approximately 3.68 and 10.52 trains could move on the proposed rail line per day, on average, including both loaded and unloaded trains,” according to the Final EIS. These trains are expected to “primarily transport crude oil produced in the Basin, but could also carry frac sand, other proppant material, steel, machinery, or mineral and agricultural products and commodities into and out of the Basin.”

STB wrote in its Dec. 15, 2021 final approval decision that “as with most other rail construction projects, the construction and operation of this Line is likely to produce unavoidable environmental impacts. But the Board also finds that the construction and operation of the Environmentally Preferred Whitmore Park Alternative, with the extensive mitigation conditions imposed, will minimize those impacts to the extent practicable.”

The project, the agency said, must follow OEA’s final environmental mitigation measures—including voluntary measures proposed by the Coalition and additional measures developed by OEA—with minor changes. The voluntary mitigation measures span from construction and rail operations safety and grade crossing safety to hazardous materials handling and spills during construction; hazardous materials transport and emergency response; air quality; water measures; and community outreach. The additional mitigation measures cover socioeconomics and environmental justice, among others.

The construction and operation of line, STB continued, “will have substantial transportation and economic benefits. … [T]he Line will bring rail service to an area of Utah that does not currently have service, provide shippers that must now rely on trucks another shipping option, and create jobs. … Rail service will eliminate longstanding transportation constraints. The availability of a more cost-effective rail transportation option could also support the diversification of local economies in the Basin, which could support additional employment and expand the regional economy. … Moreover, the Board notes the Ute Indian Tribe’s support of the project and the benefits that the Tribe has stated that it will provide. While the No-Action Alternative would avoid the potential environmental impacts of the rail project, it would not bring these benefits to the Basin or meet the goals of the counties making up the Coalition or the Ute Indian Tribe. The environmental impacts identified in the Draft and Final EIS have been sufficiently mitigated so that they do not outweigh the Line’s transportation benefits. Moreover, as explained in the Board’s January 5 Decision …, the Board can grant the Coalition’s request for authority even if all issues involving financing are not yet resolved because the grant of authority is permissive, not mandatory, and the ultimate decision on whether to proceed will be in the hands of the Coalition and the marketplace, not the Board. A grant of authority permits a new line to be built if the necessary financing is obtained. Without moving forward with the process needed to obtain Board authority, however, no new rail lines could be built, regardless of how viable the projects might be.”

The STB concluded that “the transportation merits of the project outweigh the environmental impacts and the Coalition has demonstrated that an exemption from [49 U.S.C.] § 10901 is appropriate. There also is a presumption that rail construction projects are in the public interest. Section 10901(c) provides that the Board ‘shall issue a certificate [authorizing construction activities] […] unless the Board finds that such activities are inconsistent with the public convenience and necessity.’

“Recognizing the presumption, the Board finds that this project should be approved.”

STB Chairman Martin J. Oberman—the lone dissenter among the five Board members—wrote that the project’s “environmental impacts outweigh its transportation merits,” and “[a]bsent some particularized national need for increased oil from the Basin, of which there is none, I cannot support construction of the Line.” (Download his dissent below; also read: Taking Measure of STB’s Oberman.)

Background: Court Ruling

The petitioners claimed the STB violated “several interrelated statutes and various procedural requirements enacted to ensure agencies [like STB] consider the possible adverse impacts associated with the approval of projects like the Railway,” the court wrote in its decision. “Petitioners both argue that the Board failed to take a hard look at the Railway’s environmental impacts in violation of NEPA. The County claims the Board violated the NHPA [National Historic Preservation Act] by failing to consult the County on the Railway and to evaluate the impact of the project on historic properties downline. The Center raises separate challenges under the ESA [Endangered Species Act] regarding the Board’s reliance on the [Fish and Wildlife] Service’s BiOp, which adopted the proposed action area as defined by the Board’s Office of Environmental Analysis, and the validity of the BiOp itself. Finally, Petitioners both assert that the Board erred in exempting the Railway from the ICCT Act’s full application process.”

Following is a breakdown of the Court’s decision:

• NEPA. According to the Court, the petitioners raise numerous objections under NEPA regarding STB’s environmental review of the Uinta Basin Railway. “To fulfill their obligations under NEPA, ‘agencies must take a “hard look” at the environmental consequences of their actions, and provide for broad dissemination of relevant environmental information,” the court wrote in its decision. “Here, the Board assessed the environmental impacts of the Railway under pre-2020 regulations promulgated by the Council on Environmental Quality … The CEQ ‘regulations require an agency to evaluate cumulative impacts along with the direct and indirect impacts of a proposed action.’”

While the Court said it disagreed with “many of Petitioners’ objections,” it found that “the EIS failed to demonstrate that the Board took the requisite ‘hard look’ at all of the environmental impacts of the Railway.”

According to the Court, the STB Office of Environmental Analysis (OEA) in the Final EIS “developed different scenarios for the expected increase in rail traffic on the Railway and resulting increase in oil production … As part of its cumulative impact analysis, the ‘OEA estimated the number of oil wells that would need to be constructed and operated [in the Basin] to satisfy the expected increased oil production volume scenarios’ … The EIS described its ‘estimates of future oil production’ as ‘a reasonably foreseeable development scenario based on historical data about the Basin and consultation with [the Utah Geological Survey]’ … While the Board lacks ‘direct parameters’ about the oil wells that would need to be drilled, this Court has found that ‘some educated assumptions are inevitable in the NEPA process.’”

The Court said that STB “provides no reason why it could not quantify the environmental impacts of the wells it reasonably expects in this already identified region. Further, the Board’s cursory assertion that it could confine the upstream impacts of oil development on vegetation and wildlife to areas where oil development and railroad construction would overlap lacks any reasoned explanation and is unsupported in the record … At a minimum, the Board ‘must either quantify and consider the project’s [upstream impacts] or explain in more detail why it cannot do so’ …

“Similarly, while the Board argues it cannot identify specific refineries that will receive and process the oil that it expects will be developed, the EIS identifies specific regions that will receive the oil based on expected train traffic [Editor’s Note: The regions include Houston/Port Arthur, Louisiana Gulf Coast, Puget Sound, Kansas and Oklahoma; download EIS, Appendix C below],” the Court reported. The EIS also identified “a limited number of refineries in those regions that would have the available capacity to process and refine the Uinta Basin’s waxy crude oil,” the Court continued. “The Board fails to explain why it cannot take the next step and estimate the emissions or other environmental impacts it expects in its impacts analysis … This is not a case in which the location of where the oil will be delivered or its end use is unknown … Indeed, the Board has identified the refineries that likely would be the recipients of the oil resulting from the Railway’s operation … and explained that the oil will be refined for combustion.”

While the Court acknowledged that “great ‘deference [is] owed to [the Board’s] technical judgments,’ it still must provide a reasoned explanation for its rulings.” STB “fails to adequately explain why it could not employ ‘some degree of forecasting’ to identify the aforementioned upstream and downstream impacts in light of the Board’s extensive analysis and estimations related to increased oil production,” the Court pointed out. “The Board, like any agency, is not allowed ‘to shirk [its] responsibilities under NEPA by labeling’ these reasonably foreseeable upstream and downstream ‘environmental effects as “crystal ball inquiry”’ … The Board also cannot avoid its responsibility under NEPA to identify and describe the environmental effects of increased oil drilling and refining on the ground that it lacks authority to prevent, control, or mitigate those developments.”

Additionally, the Court wrote, “given that the Board has authority to deny an exemption to a railway project on the ground that the railway’s anticipated environmental and other costs outweigh its expected benefits, the Board’s argument that it need not consider effects it cannot prevent is simply inapplicable.”

The Court also wrote that while it “recognize[s] that the Board relied on additional factors in analyzing downline wildfire risks—such as technological improvements in the rail industry and historic data on train-induced wildfires—its assertion that an increase in rail traffic of up to 9.5 new trains a day would not result in a significant wildfire risk because it would not be a qualitatively ‘new ignition source’ is utterly unreasoned … A significant increase in the frequency of which existing ignition sources travel this route equally poses an increased risk of fire. It follows that the historic data relied upon purportedly showing that train-induced wildfire has a low probability is not dispositive, especially given the concededly ‘low volume of rail traffic’ on the Union Pacific Line currently … Further, because the Board appears to have underestimated the accident risk for downline trains … , it necessarily underestimated the wildfire risk from downline derailments.

“This is not the ‘hard look’ that NEPA requires.”

Finally, the Court found that despite STB’s “assurance that the EIS’s analysis of impacts on water resources considered the impacts on the Colorado River, the Board offers no citations that explicitly reference possible impacts to the relevant downline water resources or explains why, as it says, ‘the impacts are the same and apply to both’ … Merely ‘[s]tating that a factor was considered . . . is not a substitute for considering it,’ … and there is no evidence here that the Board even considered the potential impacts on water resources downline of running up to 9.5 loaded oil trains a day on the Union Pacific Line—about 50% of which abuts the Colorado River … The Board concededly fails altogether to mention the Colorado River in the Final EIS’s discussion of impacts on water resources … This was not a ‘hard look’ under NEPA.”

• BiOp. According to the Court, STB’s “reasoning for narrowly defining the action area to not include waterways downline near the Union Pacific Line is unreasoned and fails to demonstrate a ‘rational connection between the facts found and the choice made’ … Though it is obvious that the increased traffic on the Union Pacific Line ‘would not introduce a new potential source of pollution,’ … it is entirely unclear from the record why the Board determined that the additional train traffic—with the attendant increase in ‘leaks or drips of fuel or lubricants’—’would not substantially change the severity of impacts’ on the protected species near the Union Pacific Line.”

The Court went on to say “[t]his reasoning is especially flawed given the Board’s recognition that the Union Pacific Line segment ‘currently has a low volume of rail traffic relative to the predicted traffic’ due to the Railway and the likely flawed analysis of accident risk, as discussed above. … Though we accord deference ‘on matters relating to their areas of technical expertise[,] [w]e do not . . . simply accept whatever conclusion an agency proffers merely because the conclusion reflects the agency’s judgment’ … Here, the Board failed to adequately explain its reasoning given the record evidence.”

“The [Fish and Wildlife] Service’s adoption of the Board’s proposed action area causes the BiOp itself to be flawed as a result,” the Court reported. “While the Board was required to provide ‘[a] map or description’ of the action area in its initiation of formal consultation with the Service, … the Service had an independent duty to determine the proper scope of ESA [Endangered Species Act] review. The relevant regulations even require a review of the ‘relevant information provided by the [action] agency’ that ‘may include an on-site inspection of the action area’ … The formal consultation process ‘ensures that [government action] likely to jeopardize any species protected by the ESA either not be taken without consideration of those risks or yield to safer alternatives.’ … Here, the Service never considered possible risks to protected species downline based on the Board’s faulty reasoning and therefore did not fulfill its important function under the ESA. That is not how ESA consultation by an action agency with the expert Services is supposed to work.

“The Board arbitrarily narrowed the scope of ESA review, and the Service adopted that flawed determination without interrogation. Where, as here, an agency determination is not supported by reasoned decisionmaking, ‘the agency’s decision cannot withstand judicial review’ … Both the BiOp and the Board’s Final Exemption Order, to the extent it relies upon the BiOp, are arbitrary and capricious. Not only is this violative of the ESA, but the Board also cannot satisfy its NEPA requirements by pointing to the Biological Opinion.”

• ICCT Act. Finally, the Court wrote that it agreed with the Petitioners contention that STB’s “Final Exemption Order is arbitrary and capricious under the ICCT Act.”

According to the Court, “[i]n granting an exemption from the ICCT Act’s full application requirements, the rail transportation policy provided in 49 U.S.C. § 10101 ‘must guide the [Board] in all its decisions’ … While the Board does not necessarily have to ‘address each and every one of the policy’s fifteen components,’ it ‘must consider all aspects of the policy bearing on the propriety of the exemption and must supply an acceptable rationale therefor’ … ’All that is necessary is that the essential basis of the [Board’s] rationale be clear enough so that a court can satisfy itself that the [Board] has performed its function.’”

The Court went on to say that the STB’s “fundamental task here was to ‘properly consider[] and appl[y]’ the relevant Rail Policies in its determination on the [Seven County Infrastructure] Coalition’s exemption petition … It is clear from the Final Exemption Order that the Board failed at every juncture.

“First, the Board did not provide ‘adequate attention’ to comments questioning the financial viability of the Railway and therefore did not properly consider the relevant economic and regulatory policies … As the County highlights, the Coalition asked a third party, R.L. Banks, ’to prepare a detailed 2018 feasibility study addressing the viability of the [Railway]’ ‘prior to seeking authority from the Board’ … The Center [for Biological Diversity] obtained a redacted copy of the feasibility study that it provided to the Board. … The redacted copy apparently called into question ‘the demand for the type of oil extracted from the Uinta Basin’ and the financial viability of the Railway overall …

“The Board did not address the Center’s objection that the redacted material from the study was needed to gauge the economic viability of the Railway. Instead, the Board explained that ‘nothing in the language of § 10502 . . . suggest[s] that an exemption proceeding is inappropriate if the viability of the proposed rail line is questioned.’ (‘[N]either § 10502 nor the STB’s implementing regulations indicate that an exemption proceeding is improper when the project’s financial viability is questioned.’)). It also provided ‘that the ultimate decision to go forward with an approved project is in the hands of the applicant and the financial marketplace, not the agency.’ … For these reasons, the Board determined that it ‘[did] not need the material currently redacted in the R.L. Banks 2018 feasibility study obtained by the Center, despite the Center’s claim to the contrary’ …

“The Board’s argument is essentially that the financial viability of a project, specifically whether it can get upfront and ongoing financing, does not implicate the Rail Policies, so the Board does not need to address project viability or respond to comments challenging it. This interpretation, however, runs counter to the fourth and fifth Rail Policies relied on in the Preliminary and Final Exemption Orders. As was raised in the Center’s reply to the Coalition’s petition for exemption, it would not ‘ensure the development and continuation of a sound rail transportation system . . . to meet the needs of the public,’ … ‘if the applicant were to start construction but not be able to complete the project and provide the proposed service’ due to lack of financing. … The STB decision referenced by the Center did not deal with an exemption petition but rather a full application under 49 U.S.C. § 10901, but this reasoning still has force when considering the language of the fourth and fifth Rail Policies.

“Despite its protestations to the contrary, the Board cannot ignore and, in the past, has not ignored serious concerns about financial viability in determining the transportation merits of a project …”

According to the Court, the STB “reiterates its categorical rule that ‘the ultimate test of financial fitness is in the hands of the applicant and marketplace’ so uncertainty about financial viability is not relevant to its determination … In the Preliminary Exemption Order, the Board also articulates a separate test of sorts to establish when an exemption petition should be denied in light of a project’s financial viability. It provides that when two factors—an ‘increase in project costs or uncertainty about funding’—’are both substantial and inadequately or inconsistently addressed, combined with other relevant factors, including the extent to which the marketplace will assess financial fitness, additional scrutiny may be warranted’ … But the Board insists that the there was only ‘some uncertainty’ as to the financing of the Railway, so a full application process was unnecessary …

“The Board’s reasoning is unavailing. These tests are nothing more than the adoption of a new rule without real explanation for its ‘changing position.’ … At bottom, a project that is in doubt of ever materializing or continuing to operate cannot accomplish any of the transportation merits identified by the Board. And, the Board has applied that reasoning in prior cases in which ‘[c]ommenters . . . have raised significant questions surrounding the financial feasibility of [a] proposed rail project’ … Given the record evidence identified by Petitioners—including the 2018 feasibility study—there is similar reason to doubt the financial viability of the Railway. Of course, our Court ‘may permit agency action to stand without elaborate explanation where distinctions between the case under review and the asserted precedent are so plain that no inconsistency appears’ … Here, however, the Board fails to explain how the financial uncertainty unearthed by Petitioners is meaningfully distinct from the Board’s prior precedent. In both, significant questions regarding the financial viability of the proposed project were raised. Yet, in this latter case, the Board has elected to ignore these concerns despite their application to the relevant Rail Policies. Accordingly, the Board’s adoption of this new rule of washing its hands of any concern for financial viability is ‘an inexcusable departure from the essential requirement of reasoned decision making’ …

“Second, with respect to its consideration of the environmental policies, the Board relies solely on its EIS … As we have held, the EIS is arbitrary and capricious, so those errors infect the final determination as well. Even so, the Board’s discussion of the environmental policies in the Final Exemption Order separately demonstrate that the Board did not adequately consider the incredibly significant environmental effects identified in the EIS in weighing those impacts against the uncertain transportation benefits of the Railway. The ‘cumulative’ effects within the Uinta Basin of a major expansion of oil drilling there, on Gulf Coast communities of refining the oil, and the climate effects of the combustion of the fuel intended to be extracted are foreseeable environmental effects of the project. These are effects the Board ultimately has the authority to prevent. The Board was required not only to identify those effects under NEPA, as discussed above, but also to weigh them in its ICCT Act analysis. Its failure to do so contributes to our conclusion that the Board’s order is arbitrary and capricious.”

According to the Court, the STB “is required to compare both sides of the ledger, not just acknowledge that both sides exist. And it may not completely ignore a ‘policy bearing on the propriety of the exemption’ as it did here with the energy conservation policy. … As the Board identified, on one side of the scale the Railway could result in nearly one percent of total U.S. greenhouse gas emissions and the increased rail traffic downline could cause amplified risk of wildfires, the potential of derailed trains on an annual basis, and crude oil spills in critical habitats and sensitive water resources that are home to endangered species. On the other side, the Railway may open up new markets for crude oil transportation, assuming the project is financially viable—an assumption that is not clear from this record. The Board’s consideration of these impacts and benefits was cursory at best, leaving little question that the ICCT Act necessitated a more fulsome explanation for the Board’s conclusion that the Railway’s transportation benefits outweighed the project’s environmental impacts.”

The Court concluded that “[i]t is not our job to decide whether the Board ultimately arrived at the right outcome in light of its findings. … (‘The scope of review under the “arbitrary and capricious” standard is narrow and a court is not to substitute its judgment for that of the agency.’). However, it is clear that the Board failed to adequately consider the Rail Policies and ‘articulate a satisfactory explanation for its action including a rational connection between the facts found and the choice made’ … The Board’s protestations at argument that it is just a ‘transportation agency’ and therefore cannot allow the reasonably foreseeable environmental impacts of a proposed rail line to influence its ultimate determination … ignore Congress’s command that it make expert and reasoned judgments that ‘properly consider[] and appl[y]’ the relevant Rail Policies prior to granting an exemption from its full application requirements. … Here, those Rail Policies include the environmental impacts of the Railway, and the Board failed to fulfill its obligation under the ICCT Act to consider them alongside any potential economic benefits.

“The Board failed to ‘supply an acceptable rationale’ as to its consideration of the relevant Rail Policies and therefore the Final Exemption Order was issued in violation of the ICCT Act.”