U.S. Imports Shifting East. Can the Supply Chain Keep Up?

Written by By James Miller, Partner, and Joseph Towers, Senior Analyst, Oliver WymanShipping patterns for U.S. container imports from Asia are changing, driven by a myriad of factors, from the COVID-19 pandemic and subsequent supply chain disruptions to new geographic product sources and expanded ship routing and port choices. Oliver Wyman’s research shows that a shift in imports from West Coast to East Coast may be accelerating—which is changing competitive pressures on port and inland transportation options.

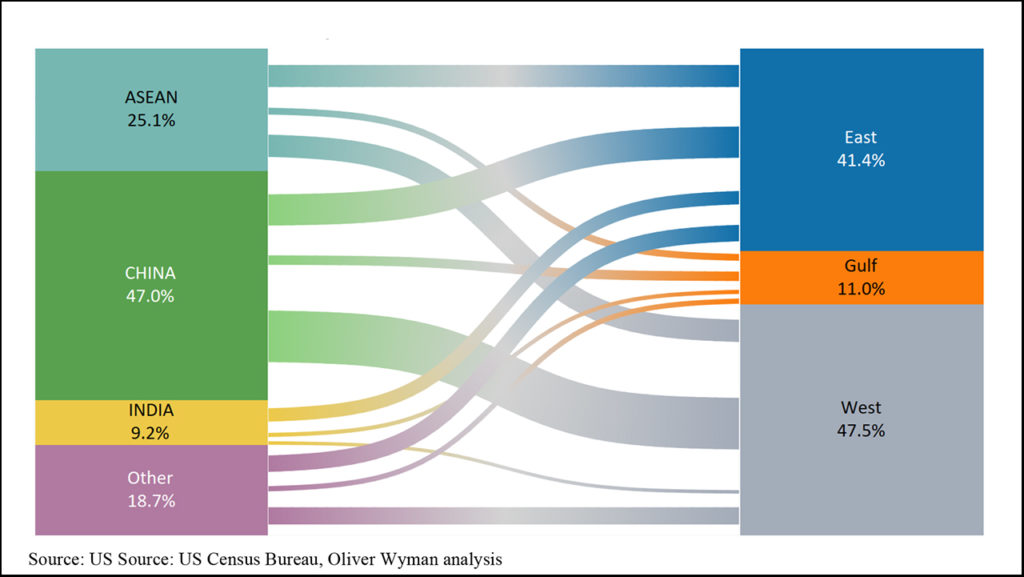

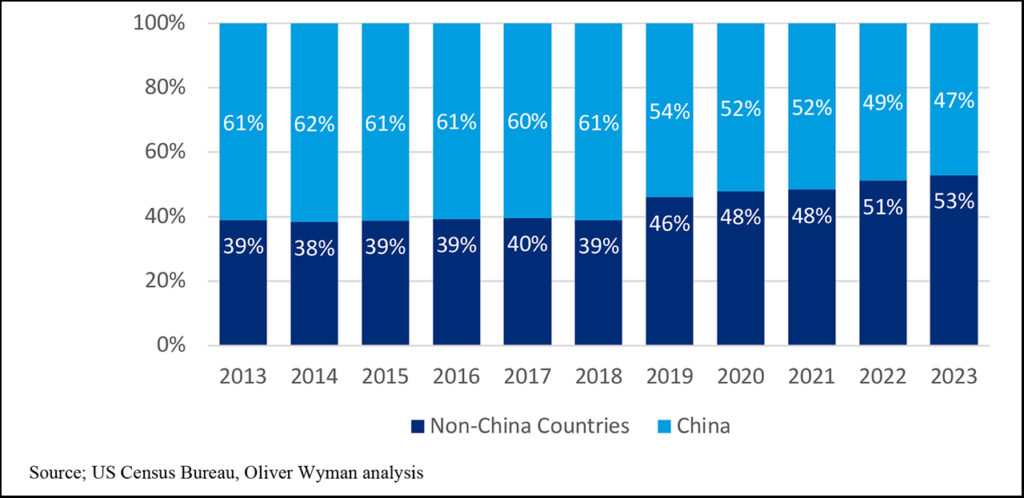

For more than a decade, China has been the largest source of U.S. imports, with U.S. West Coast ports the primary gateway for those goods to enter the country. Even today, nearly half of U.S. containerized imports from Asia originate from China (Exhibit 1) and pass through West Coast ports. But the gap between China and other Asian countries as sources for U.S. goods has been narrowing in recent years (Exhibit 2). This trend became clear starting in 2018 with the genesis of the U.S.-China trade war and was further accelerated by the supply chain disruptions associated with COVID-19. The pandemic clarified the risk to shippers of having only one supplier and the need to diversify their supply chains.

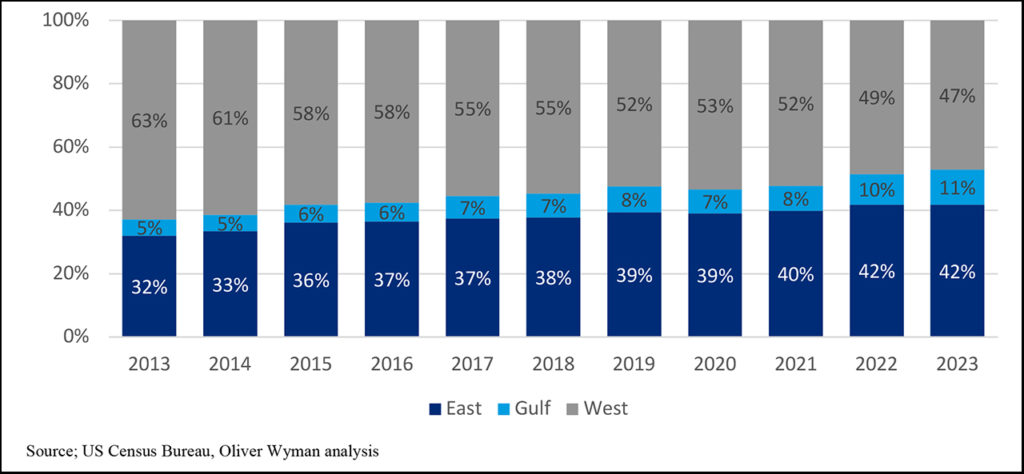

China’s historic position as the largest U.S. overseas trade partner has been weakening in terms of both market share and total volume. Between 2018 and 2023, Chinese imports fell by 3% a year, while imports from other Asian countries grew by 8% on average annually. Since other Asian countries are relatively closer to the U.S. East Coast by ship than China, imports through East Coast ports also have been growing (Exhibit 3). For example, in 2023, about 70% of imports from India passed through U.S. East Coast ports.

Other factors contributing to shippers choosing to import via East Coast ports include their proximity to population centers and port capacity expansion to accommodate larger ships. Since 58% of the U.S. population lives east of the Mississippi River, shipping containerized goods to the East Coast simplifies supply chains and reduces the amount of ground transportation required to get shipments to warehouses and distribution centers. Expansions of the Panama and Suez canals and port projects like deepening waterways and lifting bridges have made it much easier for today’s largest ships to call East Coast ports like Miami, Savanah, Charleston and New York/New Jersey. And West Coast ports have well-publicized issues that also are contributing to the shift.

While political or geographic instabilities, such as the drought impacting the Panama Canal or the Red Sea crisis can impact container volumes in the short term, the trend over the past decade shows a clear and continuing shift in Asian container imports from the U.S. West Coast to the East Coast.

East Coast Challenge

East Coast ports have made significant investments to accommodate new inbound container flows, but ongoing investment will be needed to grow their competitive advantage and avoid the service issues that West Coast ports have seen in recent years.

Inland transportation options from East Coast ports – rail and trucking – are well developed but will need to “put the pedal to the metal” to keep up with growing container volumes. The trucking industry will likely continue to be the preferred mode of transportation from East Coast ports at shorter distances. But with growing container volumes, more trucks and truck drivers will be needed.

Ultimately, short haul intermodal may be a growth opportunity for rail—which could deliver big benefits in terms of capacity, reduced emissions and less congestion on existing highway infrastructure. The opportunity for railroads to pick up more East Coast containers will require a significant shift in mindset—away from the West Coast status quo of long trains hauling boxes more than 2,000 miles—to identifying how to serve closer customers and more fastidious supply chains. Rail is less cost-competitive at shorter distances, and containers only move an average of 800 miles from the East Coast to population centers.

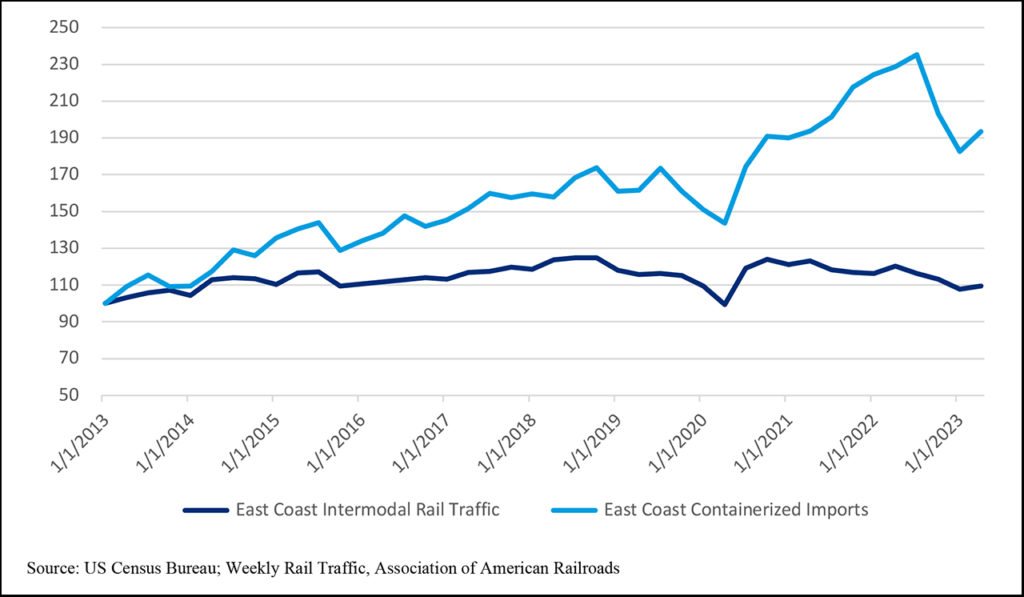

Overall, rail share of U.S. East Coast import containers has not kept pace with increasing container volumes (Exhibit 4), but railroads are beginning to recognize the substantial upside these flows could provide. One positive development has been railroads and ports teaming up to develop inland port terminals to expedite containers out of ports and closer to inland customers.

Capturing more East Coast container traffic, however, will require railroads to continue adopting more service-focused initiatives to attract and retain shippers. These include expanded on-dock rail capabilities, greater reliability and on-time performance, and tighter first- and last-mile coordination. Given the strong growth outlook for East Coast container imports—particularly as more shippers deploy diversification strategies to combat supply chain disruption—railroads will want to ensure they are maximizing their competitiveness, in terms of both customer service and economics.