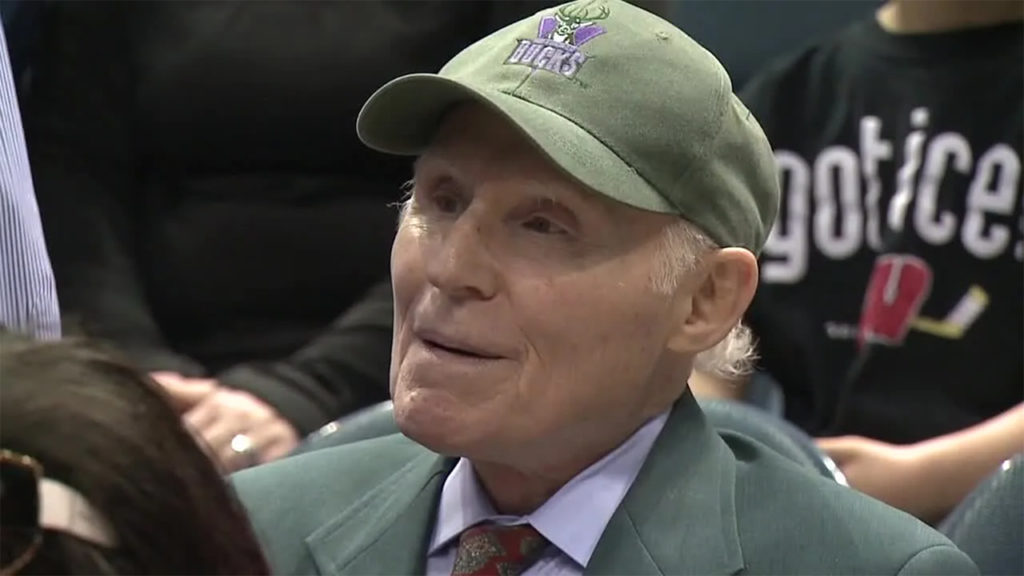

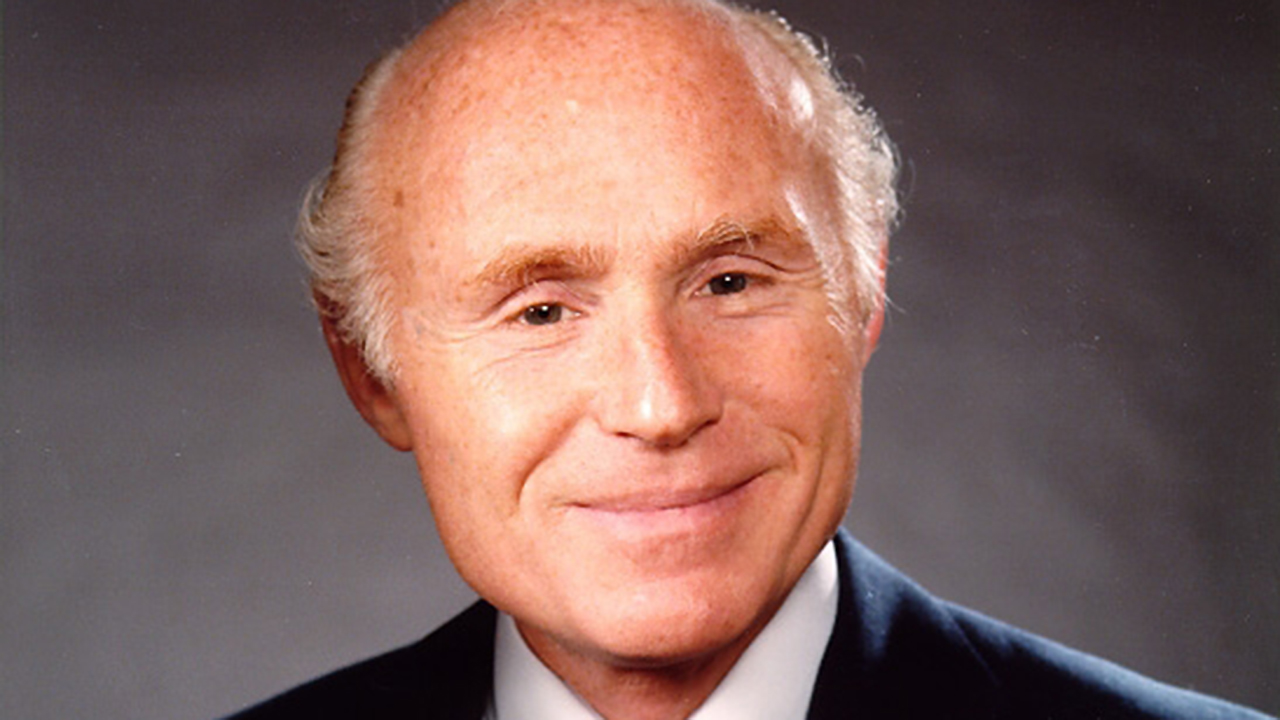

Sen. Herb Kohl, 1935-2023, Rail Shipper Advocate

Written by Frank N. Wilner, Capitol Hill Contributing Editor

Aside from being a successful entrepreneur whose name adorns 1,100 department stores in 49 states, or once being an owner of the National Basketball Association’s Milwaukee Bucks, former Sen. Herbert Hiken Kohl (D-Wisc.), who died Dec. 27 at age 88, also leaves a legacy of advocating greater competition among railroads.

Unlike many in Congress who introduce, on behalf of special interests, legislation to transfer private-sector wealth in exchange for campaign contributions, Kohl steadfastly forswore pay-for-play entreaties. Although his efforts on behalf of shippers lacking effective transportation alternatives to rail (captives) were not successful, they were sincere—intended to increase competition—as Kohl revered his own private-sector career of clawing for market share in a highly competitive retail marketplace.

Railroads, which suffered acid reflux from Kohl’s exertions, consider their own lobbying activities as protecting private property from such legislative mischief—that private-sector wealth is not a public trust to be shared equally. The intersection of economics, democracy, politics and public policy can be complicated.

Elected to succeed retiring fellow-Democratic Sen. William Proxmire in 1988, Kohl became a consequential captive-shipper ally. As a Judiciary Committee member in 2006—and later as chairperson of the Antitrust Subcommittee—Sen. Kohl advanced legislation to place railroads more fully under the antitrust laws (they having an exemption where the Surface Transportation Board—nee, Interstate Commerce Commission—regulates mergers, rates and practices).

Kohl’s 2006 sponsorship of a Railroad Antitrust Enforcement Act (S. 3612) encouraged attorneys general from 17 states and the District of Columbia to lend support, jointly writing that “rail customers in our states in a variety of industries are suffering from the classic symptoms of unrestrained monopoly power [and] unreasonably high and arbitrary rates and poor service.” After railroads successfully urged the bill’s defeat in committee, Kohl tried again in 2007 with a same-named S. 722. While this one successfully exited the Judiciary Committee, it failed to gain a Senate floor vote.

Kohl tried again in 2009 with S. 146, which was duplicated in the House by H.R. 233 as introduced by then-Rep. (now Sen.) Tammy Baldwin (D-Wisc.). Both bills intended to send rail merger applications directly to the Justice Department’s Antitrust Division and authorize state attorneys general and shippers to sue, under the Clayton Antitrust Act, for three-times damages and pursue court orders halting “anticompetitive rail conduct.”

With a Senate floor vote on Kohl’s Judiciary Committee-approved S. 146 promised by Majority Leader Harry M. Reid (D-Nev.), Commerce Committee Chairperson John D. (Jay) Rockefeller IV (D-W.Va.), joined by Commerce Committee members Kay Bailey Hutchison (R-Tex.), Frank Lautenberg (D-N.J.) and John Thune (R-S.Dak.), moved to keep the Kohl bill from a Senate floor vote.

In a “Dear Colleague” letter signed by Rockefeller, a tabling of the Kohl measure was urged. The reason was alarm that if the Kohl bill were first passed on the Senate floor, a separate Commerce Committee bill—also focusing on railroad economic regulation—could lose support and not be teed-up for a vote.

Rockefeller wrote to Senate colleagues, “We strongly believe that regulation of railroads should be addressed in a comprehensive measure rather than in a piecemeal fashion on one narrow aspect. We have been working intensively on a comprehensive overhaul of [the Surface Transportation Board]. While we support strengthening the application of the antitrust laws to the railroad industry, and will work to do so, [the Kohl bill] is much more expansive and touches on matters [already the subject of a Commerce Committee bill].”

Kohl acquiesced, with he and Rockefeller jointly writing colleagues, “The Commerce and Judiciary Committees intend to work together on comprehensive rail competition legislation. We hope to shortly have a bipartisan package that reforms the Surface Transportation Board and repeals the railroads’ antitrust exemption.” Majority Leader Reid then removed the Kohl bill from the list of those scheduled for a floor vote.

In fact, Kohl had been hoodwinked. Rockefeller, with cosponsorship by Hutchison, Lautenberg and Thune, introduced in the Commerce Committee the Surface Transportation Board Reauthorization Act of 2009 that, while containing many objectives sought by captive shippers, was vacant of Kohl’s antitrust intentions.

With Kohl’s Railroad Antitrust Enforcement Act having voluntarily been removed from Senate floor consideration, Baldwin’s matching House bill became academic. Ironically, the Rockefeller et al Commerce Committee bill, intended to take precedence, failed Senate floor passage.

Kohl tried again in 2011. Joined by Sen. David Vitter (R-La.), they introduced a similar Railroad Antitrust Enforcement Act (S. 49), but its time had passed and it died in committee.

In 2015, with Kohl having retired from the Senate in 2013 (and Rockefeller but months from retirement) another Surface Transportation Board Reauthorization Act—again devoid of antitrust provisions—was introduced by Thune, who had succeeded Rockefeller as Commerce Committee chairperson. This bill gained Senate and House approval and was signed into law. Railroads remain largely exempt from antitrust law.

Among those with whom Sen. Kohl consulted on his antitrust legislation was attorney and captive shipper advocate Robert G. Szabo, formerly a legislative aide to Sen. Bennett Johnston (D-La.) and at the time executive director of captive-shipper organization Consumers United for Rail Equity (CURE). Now retired in central Virginia, Szabo told Railway Age:

“I remember well this collision between the Judiciary and Commerce committees and Senators Kohl and Rockefeller. The Rockefeller staff view, which became the Rockefeller view, was that the shipper interests would only get one shot at legislation on the floor of the Senate and that should be the Rockefeller bill and not the Kohl bill. It resulted in one of the early legislative mistakes that doomed our best opportunity to achieve legislation.

“The Rockefeller staff proved its ineptness. The captive shipper view was that we should have pressed to pass the Kohl antitrust bill in the Senate, as Majority Leader Reid had promised Kohl a floor vote on this bill. The railroads would then be much more eager to agree to some form of shipper reform bill as a substitute for the antitrust bill.”

In defense of Rockefeller, his distaste for abuse of market power and support for bringing railroads more under the antitrust laws was no less genuine than that of Sen. Kohl. In fact, Sen. Rockefeller often recalled his great-grandfather’s well-documented 19th century market power over the railroads. He would recite how John D. Rockefeller Sr. dictated to railroads not only the price he would pay for moving oil, but the price his competitors would pay, along with the amount of a rebate on competitor freight rates railroads were to pay Rockefeller—musing that the shoe was now on the other foot.

Post-scripts:

After the STB in 2000 imposed a 15-month industry-wide merger moratorium, causing Canadian National and BNSF to cancel a proposed merger, BNSF CEO Rob Krebs was quoted that he once “favored shifting [economic regulatory] jurisdiction over railroads to the [Antitrust Division of the] Justice Department. Today, I wish I’d worked harder to make that happen.” Yet, subsequently, BNSF was among those strenuously opposing each of the Kohl initiatives to bring railroads more fully under the antitrust laws.

Remarkably, Association of American Railroads President William H. Dempsey also once advocated bringing railroads under the antitrust laws. At a 1987 House Antitrust Subcommittee hearing (prior Kohl’s election), where Dempsey was confronted by Rep.. Michael Synar (D-Okla.) that in addition to being insulated from the antitrust laws railroads also enjoyed separate regulatory-agency protection when exerting market power, Dempsey responded, “If the notion is that the railroads are somehow escaping both, then the thing to do, I suggest, is to … subject the railroads fully to the antitrust laws.”

Coincidentally, Kohl and Jay Rockefeller relaxed on adjacent ranches near Jackson Hole, Wyo. The 1,106-acre Rockefeller ranch (actually owned by cousin Laurance Rockefeller)—on which President Bill Clinton and his family vacationed in 1995 as guests of Jay—was donated in 2001 by Laurance to the National Park Service to become part of Grand Teton National Park. Kohl donated his 990-acre ranch in 2014 to the Trust for Public Land (now owned by Bridger-Teton National Park, adjacent to Grand Teton National Park).

As for Rep. Baldwin, she won election in 2012 to succeed the retiring Sen. Kohl, was reelected to that Senate seat in 2018 and seeks reelection in 2024. As a senator, she remains supportive of captive shippers, most recently introducing the Improving Reliable Rail Service Act (S. 2071). Currently before the Commerce Committee, the bill would ensure railroads provide transportation or service in a manner that fulfills the shipper’s reasonable service requirements. Unlike Sen. Kohl, Sen. Baldwin accepts political contributions from special interests, including electric utilities and rail labor unions.

Scores of narratives such as this are found in Railway Age Capitol Hill Contributing Editor Frank N. Wilner’s newly published book, Railroads & Economic Regulation, available from Simmons-Boardman Books at www.transalert.com, 800-228-9670.