NEARS Report: Oberman’s Regulatory Views

Written by Jim Blaze, Contributing EditorJim Blaze reporting from Portland, Me., NEARS: STB Chairman Marty Oberman delivered an interpretation that suggests his independent members are still awaiting insight from the private “Big Six” as to reciprocal switching minimum service metrics for service. It’s not a rate and overall open-access focus at all says the STB leader. And separately, Tony Hatch and Jason Seidl seemed to agree.

The person a decade ago that many might have never considered to be holding the gavel of rail freight regulation in his hands walked slowly but steadily to the podium to close this NEARS (Northeast Association of Rail Shippers) 2023 Fall Conference session. He’s the Chairman of the five-person railway regulatory authority charged with commercial oversight involving rates, costing and disputes among railway carriers and the customer shipper/receiver logistics community. The STB also oversees disputes involving geographical, environmental and community operations and service standards and performance.

Reminder: STB doesn’t oversee rail safety.

Marty Oberman warned us that he could not comment deeply about pending matters like reciprocal switching. But he could describe procedural schedules and open issues without offering outcome suggestions. Why not? It came down to protecting the open debate and discussion process that he sees as essential to seeking unbiased consensus among the parties—and indeed between he and his fellow four other commissioners.

He wasn’t standing before NEARS to deliver a sales pitch for a favored personal agenda. Still, he was open about stating some of his logic as to the pros and cons of the issues before the entire Board.

Oberman covered the STB’s view about the recently authorized CPKC merger as being fundamentally about a unique expansion of international Canada-U.S.-Mexico service as a new competitive initiative, largely intermodal from his point of view. He pointed out that, since the approval (and merger execution), the combination has given rise to a competitive service offered by Union Pacific and CN.

Interestingly, Oberman’s observations were heavily focused on intermodal competition rather than carload rail-to-rail competition. The most controversial point, he seemed to allow, is the still-open and still-under-research and discussed reciprocal switching topic. His lawyers were in the room observing his comments from the podium, he warned us. So, he would be restrained from wandering too far afield as to his or the Board’s thinking while the oversight proceeding was still active. But it is clear from his extensive remarks that the Board has pivoted toward the failure of service performance as the real public interest in the reciprocal switching challenge, as a possible operations solution.

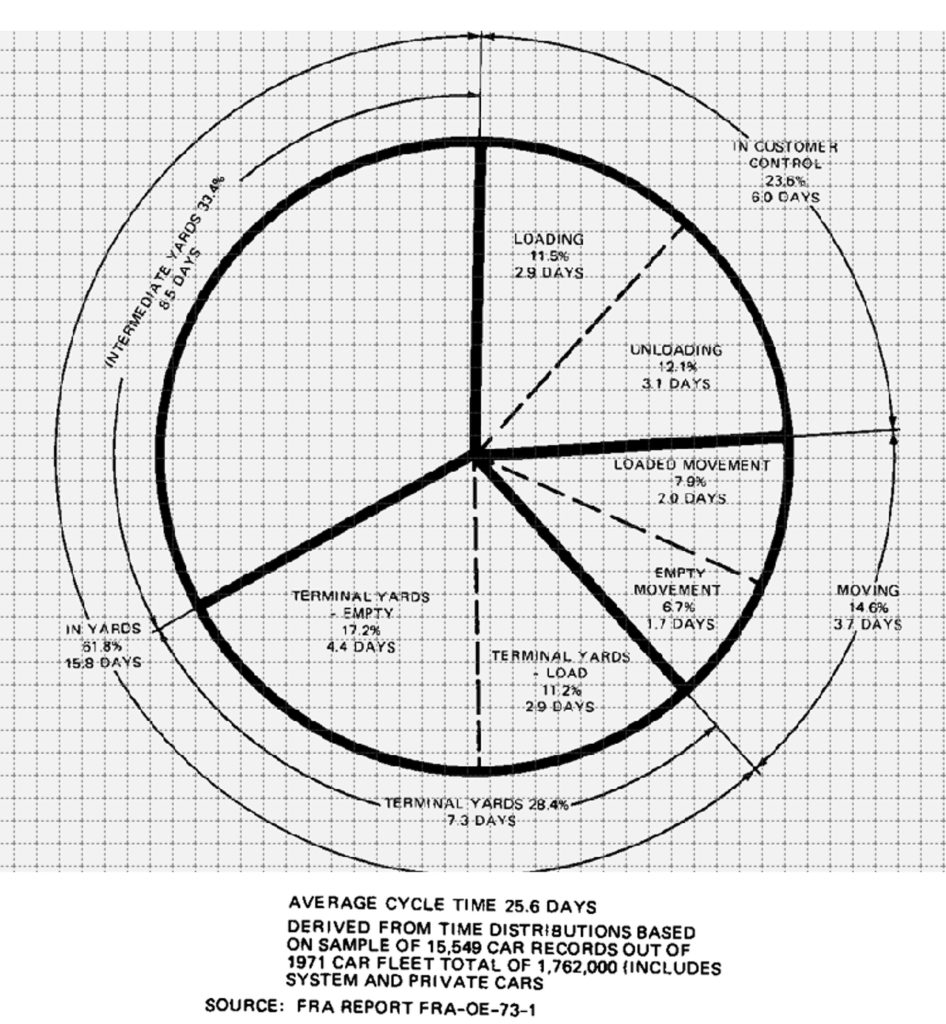

Service is hardly as robust as it needs to be is the way Oberman expressed the Board’s view—a failure to perform up to expected standards for the good of the customers and the national interest, an embarrassing failure recognized within railroad executive offices. It has essentially been documented during the Board’s open hearings this past year as a failure directly related to railroad crew (worker) shortages.

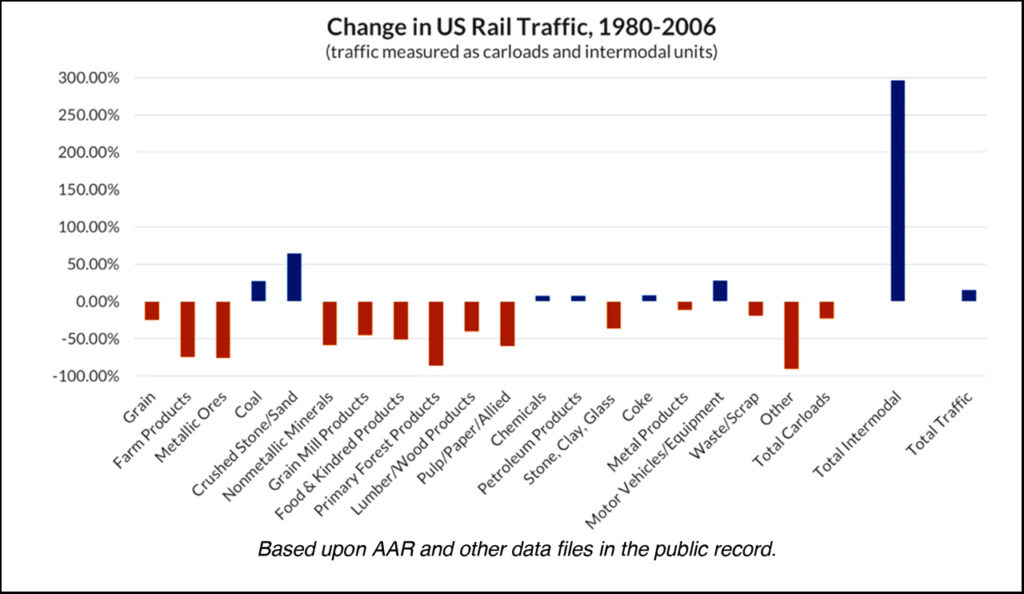

Oberman’s challenge: What are the railroads’ long-range plans to deal with the worker shortages that result in acknowledged service failures? He acknowledged that even the railroads know that there has been almost no growth in railroad carload traffic over the past two decades. That’s well-backed-up by AAR and other data sources. Yet growth in ton-miles, tons, carload units, and the like measures are continually touted as the corporate goal. Obviously, he noted, there is a disconnect here in the forward-looking growth aspirations.

Given the vast growth in the U.S. economy, “The railroads must be embarrassed that they have not been contributing to this national economic performance,” Oberman said. “Did the railroads choose the harvesting of profits instead of focusing on their opportunity for capturing truck market share and lowering environmental pollution?” That is indeed a public policy question he put to the NEARS audience.

Oberman challenged rail leaders to put some beef behind their continued articulation of their own recognized need for volume growth, not just revenue and pricing yield growth. Those are different targets, and clearly the PSR business model of superior net cash flow has been overwhelmingly achieved, he noted. But competing for market share against trucks? Not too successful.

The STB has therefore decided to seek a rebalancing of the service aspect of railroad freight, simplistically described as a means to increase service accessibility at reasonable rates (cost allocation) in specific geographic locations across the nation. Not an everywhere solution, not at all like the European nationalized “open access” business model.

The railroads need to increase their capacity, he said. “They are uniquely situated to offer a better environmental public benefit, with possibly millions of annual trucks diverted to railways. The railroads by their own admission make it clear that the railroads cannot attract traffic from trucks unless they provide more reliable service, which they cannot do unless they provide more workers to keep things moving across their private networks. What kind of a business needs to rely on a government official to lean on to help it make more money? Apparently, only a railroad.”

Meanwhile, a Crain’s business survey has found that close to 90% of offshore shippers are studying a shift to nearshore or to onshore manufacturing and supply chain distribution back toward North America. How’s that going to help the railroads if they lack the critical resources of skilled labor, locomotive power and higher track capacity across selected known bottleneck areas of the U.S. rail network? That was Oberman’s clear challenge.

Oberman did acknowledge that a new group of managers might be more receptive to shifting their market growth focus now that so much internal productivity (efficiency from lower operating ratios) has been the result of the past half decade or so of operational and asset re-engineering using parts of the E. Hunter Harrison PSR business model. How that high efficiency be now turned to top-line volume growth in traffic units is the opportunity question. Oberman recognized that multiple executives are taking positive steps to have the resources like people to support the pivot towards growth, taking, for example, steps to improve first-mile and last-mile service performance, because service delivery of carload movements in the sometimes below 60% on-time ETA level isn’t going to get the job done.

“Service on reasonable request” is probably the legislative target that the Board is working to ensure. The so-called reciprocal switching review is now awaiting suggestions from the rail operators and the customer base as to how to define serious service failure, whose metric measurement is clearly unacceptable behavior. So, the ball is in the railroad court so to speak. What is senior management’s understanding of what level of service failure constitutes a likely continued truck reliance? This is interesting because the Board is seeking a logistician’s answer, not a railroad operational reason or a legalistic response.

What a surprise! Most observers had expected the STB to be almost solely focused upon rate and forced access as the geo/political solution. Instead, the Board through its hearings process is morphing toward a policy for reciprocal switching access built upon the failures of performing essential—and often contractually promised (advertised/promoted) service standards. Who saw that coming?

Maybe Jason Seidl and Tony Hatch did. They picked up on this policy switch in their day-before “NEARS Ying and Yang” open discussion remarks. The STB, from this NEARS discussion, really does not want to promulgate a big-stick enforcement program. It seems to be bending over for a rebalancing that allows both the carriers and the customers to define metrics that define minimal poor service delivery as the public reaction point.

Will the parties pick up on this during this responsive filing period? Oberman is asking, not telling. Did all the NEARS audience pick up on this?

Blaze’s Takeaways

Chairman Oberman spoke clearly, not as one of five who get to vote. He was asking for input. Any NEARS member could submit comments. It doesn’t have to come from the AAR or from a legal department.

The Board is open mostly to pro-competitive options that improve both the resiliency of our nation’s logistics services and their contribution towards safer environmental delivery.

The silence about rate regulation? That too is noticeable.

Oberman is optimistic that now, as eventually was likely to happen, the Wall Street and railroad executive suites both realize that the absence of a growth and market share increase strategy will probably result in continued shrinkage of the railroad’s supply chain role.

He noticed that the railroads just are too slow at technology adoption. What’s taking so long? JB Hunt and others have that sense of supply chain management high-tech use urgency. Meanwhile, rail freight is the trailing mode. Rail should be moving faster.

Ironically, I remember when the railroads themselves promoted reciprocity agreements as a way to improve market coverage and retain their once-dominant share. Reciprocal agreements were used to fill in missing geographic coverage for key customers. It was a series of negotiated bargains for access, not a penalty contract as it so often seems today.

A Missing Message

The question for NEARS members might be this: How do Oberman’s remarks and the Board’s upcoming reciprocal switching service standards impact the short-haul, mostly delivered (terminated) freight directional pattern across New England? Yes, there was lots of commentary describing national patterns Yet, the New England market is somewhat unique. It’s less of a Class I vs. Class I competition and service environment. It’s much more of a pattern with one dominant Class I (CSX) and a bunch of short lines that require a higher standard of ETA actual vs. constructed delivery performance.

Or, it’s a question of timely executing the Norfolk Southern/CSX bargain for selected NS overhead trackage rights between the Albany N.Y. region and the Ayer MA via the old Conrail main lines, via Springfield and Worcester. What’s the reported hangup, discussed as rumors?

Attendees should not too quickly dismiss the recession risks. Specific to the Chairman’s excellent remarks, there still is the uncertainty of how the railroad boards might react to manpower plans if New England as a specific location is hit by energy price surges and lower market demand for lumber, and associated merchandise found in domestic and international ISO containers that enter this region. If a regional recession hits Massachusetts and Maine, and lingers into the second or third quarter of 2024, what happens to the rail work forces there? What’s that risk? But a reasonable discount might allow for a 30% possibility. That’s less risky than probable, but it should not be ignored.

These are likely topics for the NEARS Spring 2024 conference.

Possible Metrics for STB Consideration

As to what service standards could be used from regulatory minimums far below best industry practices, we need to keep the different definitions in mind. The highest definition of a service might be where the delivery is motivated to benefit the customer as their priority rather than the priority of the carrier—more like world a class act, probably by a trucking company. Trucking actual ETA is ~one-hour window.

- Best of carload might be a unit train at 1 to 7 hours, on the day promised.

- Best of parcel or perishable carload rail, within 2 to 4 hours.

- Best of mixed carload within 88% to 94% ETA of the day promised.

- Nominal carload average, ~80% to 85% day 1 of promised expected delivery.

- Mediocre definition offered by logisticians: 24 hours late.

(The above standards are from a 2004 review for the FRA Office of Policy Planning. I was one of the authors.)

What commodities and when was the first often called Rail Freight North American Renaissance period? When I was a lot younger. They were led by Powder River Basin Coal and the intermodal surge. Both services were enabled by engineering product design of heavier-axle-load cars and double-stacked container platform cars plus railroad height clearance construction. No such additions are planned for the coming decade—nothing for the NEARS region other than CSX’s Baltimore tunnel.

Independent railway economist and Railway Age Contributing Editor Jim Blaze has been in the railroad industry for close to 50 years. Trained in logistics, he served seven years with the Illinois DOT as a Chicago long-range freight planner and almost two years with the USRA technical staff in Washington, D.C. Jim then spent 21 years with Conrail in cross-functional strategic roles from branch line economics to mergers, IT, logistics, and corporate change. He followed this with 20 years of international consulting at rail engineering firm Zeta-Tech Associated. Jim is a Magna Cum Laude Graduate of St Anselm’s College with a master’s degree from the University of Chicago. Married with six children, he lives outside of Philadelphia. “This column reflects my continued passion for the future of railroading as a competitive industry,” says Jim. “Only by occasionally challenging our institutions can we probe for better quality and performance. My opinions are my own, independent of Railway Age. As always, contrary business opinions are welcome.”