Moving Forward—at Restricted Speed

Written by David Peter Alan, Contributing Editor

Photo by John Livsey/Metrolink

PASSENGER RAIL OUTLOOK, RAILWAY AGE JANUARY 2024 ISSUE: Charles Dickens began A Tale of Two Cities, his saga of the French Revolution, by saying: “It was the best of times, it was the worst of times …” That could also be said for Amtrak and rail transit in the U.S. for the upcoming year. I opened a similar article with the same quotation one year ago, and indications seem to have moved toward the “worse” side of the continuum, for rail transit, anyway.

The indications for infrastructure have not looked this good in decades, but from the riders’ point of view, the aspect is hardly a solid green. It will be more like “Proceed at Restricted Speed” (NORAC Rule 290) or “Movement at Restricted Speed” (GCOR Rule 6.27) toward an uncertain future, as the prospect of better transit and more trains that should result from it work their way through the regulatory process, which seems to run on perpetual slow orders. The upcoming year and beyond could also be the worst of times for transit riders, as government funding that kept transit going through the COVID-19 crisis begins to run out. As always, politics rule, and the political instability in effect today will endure, culminating in a Presidential election with more novelty and uncertainty perhaps than any other since 1876. We will learn more about the unsettled political situation as time goes by, but the upcoming election could set the stage for what will happen to Amtrak and much of our transit for many more years to come.

A Word About Brightline

Everybody’s talking about Brightline, and with good reason. It’s an innovative private-sector railroad, running in South Florida, which recently introduced service further north to Orlando Airport (above). That service has been successful so far. While we don’t know how it will fare in the long run, Brightline has demonstrated that a privately funded railroad can improve a line, build new track and operate on it, and plan for expansion. That includes plans both for Florida and for Brightline West, which is slated to run between Las Vegas and the Los Angeles catchment area. It also recently announced a $3 billion grant to the Nevada Department of Transportation from the Federal-State Partnership for Intercity Passenger Rail Grant Program.

Amtrak: Infrastructure vs. Equipment?

The Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA), also known as the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (BIL), was passed and signed on Nov. 15, 2021, and included plenty of money for Amtrak. For example, it authorized grants for Amtrak over five years, including $1.2 billion for the Northeast Corridor (NEC) and $2.45 billion for the rest of Amtrak (long-distance and state-supported routes elsewhere) for FY24. All of them are geared toward infrastructure improvements.

It is true that better infrastructure could expand capacity to accommodate more trains, but it is unclear how many new lines will be added to the Amtrak route map, or even how many more trains will be added to the schedules on existing lines. We know that, in essentially all cases, the improvements must be funded and then built before the lines in question can host more passenger trains, so it will be several years before riders can go to more places or have more choices of when they can go to the places that Amtrak serves now.

Amtrak’s skeletal long-distance network (14 routes, the same number as when Amtrak started in 1971) is again running daily (except for the two tri-weekly trains, and there are efforts to restore them to daily operation), but it took a long time for that to happen, and capacity still runs below pre-COVID levels. Earlier this year, the Capitol Limited and the Sunset Limited ran with a single coach and a single sleeping car, along with food service cars. Other trains also ran with consists that were shorter than during pre-COVID times, despite increased demand for space on all travel modes lately. An accelerated program to repair equipment sitting out of service at the Beech Grove shops would help, but only enough to restore pre-COVID levels of capacity, at best.

Without new equipment, expansion is out of the question. That includes more cars on existing trains; more trains on existing routes; and new routes, like between Meridian, Miss., and Dallas on Canadian Pacific Kansas City, first proposed by John Robert Smith more than 20 years ago, when he was Chair of the Amtrak Board and Meridian’s mayor, and now under active consideration.

It will not be easy for Amtrak to get equipment, either. Debut of new Alstom-built Avelia Liberty (“Acela II”) trainsets on the NEC (above) has been delayed until sometime this year due to testing and certification problems encountered following successful tests at the TTC in Pueblo, Colo. As recently as Sept. 29, 2023, Amtrak Assistant Inspector General James Morrison issued a 44-page report that specified those problems (OIG-A-2-23-013). Meanwhile, the “Venture” cars purchased from Siemens for use on Amtrak’s Midwest corridors and by VIA Rail Canada on its corridors in Ontario and Quebec are steadily entering service, replacing outdated equipment.

Amtrak also needs equipment to replace the Superliner cars (nearly 40 years old) and the Amfleet II cars used on long-distance trains in the East (now over 40), but it would still take several years before they can be delivered, tested, and certified to enter service. Assistant IG Morrison initiated an audit of the ordering process on Oct. 13, 2023 (Project Code 002-2024). Can the existing fleet last long enough to keep the current long-distance network going until new equipment arrives? Maybe, but it’s still possible that equipment shortages could affect the entire long-distance network. Time will tell.

Amtrak is not promoting new long-distance trains, concentrating instead on new state-supported corridors. The Federal Railroad Administration (FRA) has announced modest grants for studying several, but the issues I raised nearly three years ago (“Amtrak’s 2035 Map: Hopes and Challenges,” April 9, 2021) are still pertinent. Of the roughly 40 routes mentioned as possibilities, only one is slated to open in 2024: Gulf Coast service between New Orleans and Mobile, with two daily trains in each direction. Even getting that modest amount of passenger service necessitated the “Second Battle of Mobile” before the Surface Transportation Board, which we reported in detail throughout the proceedings.

We don’t know how many of the proposed routes will ever run, how many states will be willing to spend the money that will be required to keep them going, how strongly the prospective host railroads will challenge a proposed route the way CSX and Norfolk Southern did with the Gulf Coast route, or when any of the routes that survive the process will actually begin to host passenger trains. It’s reasonable to expect that some of the proposed services will eventually run, but some have been proposed for decades, and those proposals have still not been implemented. FRA’s Corridor Identification Program and its grants for corridor development will help to some extent, but this is a preliminary step.

There are ongoing projects on the NEC like the Baltimore Tunnel and the Gateway set of mega-projects in the New York/New Jersey area, but they seem geared toward local results. Many rider-advocates, especially outside the Northeast, view Amtrak as favoring that region above others and cite the preponderance of Amtrak Board members from that region. Still, it seems unlikely that Amtrak’s Northeastern service will change soon, although there is action in Virginia. The state is acquiring and improving tracks for passenger service along rights-of-way owned by CSX and NS, and adding local trains from Washington, D.C., on Virginia Railway Express and on Amtrak-operated routes to Richmond and through Charlotte to Roanoke, with an extension to Christiansburg in the future. One project that will someday increase capacity for Virginia is a companion span alongside the Long Bridge over the Potomac River between Alexandria and Washington.

Slow Transit Progress

For 77 days in 2019, I held the distinction of having ridden all the operating rail transit in the U.S. Since that time, expansion has proceeded at a slow pace, with eight new segments opening over the past four years in the continental U.S. (two per year), plus the first segment of HART’s Skyline Rail, a line plagued by delays for years, but where an extension is slated to open in 2025.

The IIJA/BIL includes grants for transit projects, too, but the Federal Transit Administration does not recognize a distinction between rail transit and busway projects. Of the 64 projects on the agency’s grant list, only 25 pertain to rail. Some, like the Hudson Tunnel Project that would build a new tunnel between New Jersey and New York City as part of the Gateway Program, are huge. Many are much smaller.

There are a few places where expansion projects are under construction and might open in 2024. Candidates include Massachusetts Department of Transportation’s South Coast Rail between Boston and New Bedford and Fall River and the East Link Extension on Seattle’s Sound Transit. More new starts are projected for 2025.

Changing Ridership Patterns

Commuting, including by rail, is changing, as a result of technology developments that facilitate working remotely, the adoption of which was accelerated by COVID-19. Ridership tanked in 2020 and 2021, when many offices were almost empty. It’s higher now, but its character has changed. Many former commuters have not returned to the office five days per week. A pattern seems to be emerging where many employees go to the office two or three days per week, while working remotely the other days.

On New Jersey Transit and other regional railroads, ridership is lighter on Mondays and Fridays than on the other three weekdays. Weekend ridership is back to pre-COVID levels, and some weekend trains are crowded to the point of standing room only. This situation raises the question of whether capacity is being wasted on a decreasing number of traditional peak-period commuters and withheld from an increasing number of off-peak and weekend riders. Some agencies, including NJ Transit and Metrolink in Los Angeles, have initiated new fare structures, but have not changed schedules to reflect ridership changes. SEPTA in the Philadelphia area has not restored the pre-COVID level of weekend service. Can we expect much change in 2024?

Another change wrought by the virus was federal aid for the operating side of transit, included in §3401 of the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021. Before the virus struck, federal aid was given to transit providers as an ancillary addition to highway assistance for the states, and it was generally restricted to capital improvements. The operating assistance that came when the virus was ravaging transit ridership was designed to be temporary, and that money will run out within the next year or two.

Transit is in trouble in many cities, particularly major transit systems, all of which were hit hard by declines in ridership when fewer workers were required to go to work sites, and almost everybody reduced the number of trips they took. Today, both regional/commuter rail and local rail transit are facing severe difficulties. We have reported on transit woes at the MBTA in Boston; SEPTA; WMATA in and around Washington, D.C.; Muni and BART in San Francisco; New York’s MTA; NJ Transit; and others. Problems include employee shortages at many agencies, equipment that has become old and unreliable, and difficulties with infrastructure that require expensive repairs.

If there is one overarching threat to transit today, it is the “fiscal cliff”—the impending financial catastrophe that many agencies will face when the COVID-19 relief money runs out. That could happen at New York’s MTA as soon as late in 2024. State officials, with some participation by city leaders, are thinking about how to raise the money necessary to keep the transit going, with the understanding that New York City needs strong transit to survive. However, not all local officials are taking such steps.

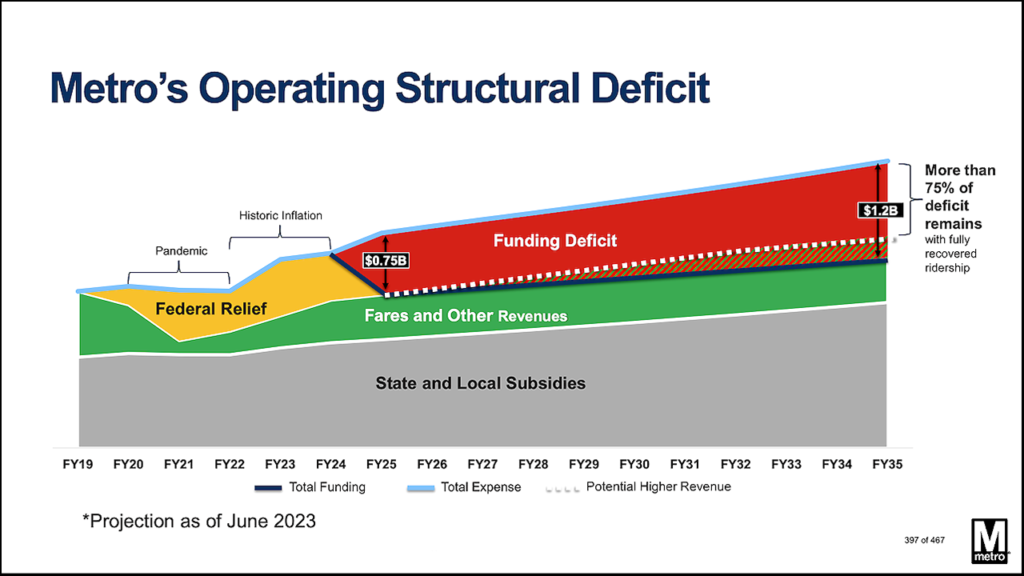

Elsewhere, the day of reckoning will probably come sometime in 2025. WMATA is facing a $750 million deficit (above). NJ Transit, which has never had a legislatively mandated source of stable and secure funding, is facing a shortfall of nearly $1 billion in less than two years. There isn’t room in this article to report on every transit agency’s financial woes in detail, but even the agencies that are planning expansions or other capital projects know (or should know) that capital grants do not pay for operations, even though some agencies are using a portion of their capital funds for the purpose, believing that they have no choice.

Politics Rule As Usual

We all know that Amtrak and the nation’s transit are subject to politics at the federal and state levels. We also know that, if there has ever been a year that anything can happen in politics, this is it. Biden and Trump might face each other in a rematch, but given Trump’s criminal indictments and concerns with both men’s advanced age and health, we can’t be sure of that. That goes for Congressional and state races, too. Republicans in the House proposed slashing Amtrak’s funding drastically, but Democrats and a few Republicans who support Amtrak can prevent that result, for now, anyway. If Trump somehow retakes the White House and the Republicans assume control of both Houses, all forms of passenger rail will probably suffer. If Biden and the Democrats win, it probably will not be as bad, although it seems unlikely that either Amtrak or transit will be out of the woods. Much will depend on the states and what they are willing to fund, another extremely unsettled situation.

At the Light Rail Conference sponsored by Railway Age and Railway Track & Structures this past November, I raised the possibility that transit providers could have brand new infrastructure, but not enough money to operate it. That still seems like a possibility at this writing. The indication now appears to call for restricted speed going forward. There appears to be plenty of reason for that, most notably the probability of a solid red aspect and an indication to STOP further down the track, but not far from here.

David Peter Alan is one of America’s most experienced transit users and advocates, having ridden every rail transit line in the U.S., and most Canadian systems. He has also ridden the entire Amtrak and VIA Rail network. His advocacy on the national scene focuses on the Rail Users’ Network (RUN), where he has been a Board member since 2005. Locally in New Jersey, he served as Chair of the Lackawanna Coalition for 21 years, and remains a member. He is also Chair of NJ Transit’s Senior Citizens and Disabled Residents Transportation Advisory Committee (SCDRTAC). When not writing or traveling, he practices law in the fields of Intellectual Property (Patents, Trademarks and Copyright) and business law. Opinions expressed here are his own.