Welcome to Amtrak Study Hall (UPDATED Aug. 14 with Additional Commentary)

Written by William C. Vantuono, Editor-in-Chief

Amtrak photo

The Federal Railroad Administration’s Congressionally mandated Long-Distance Service Study, launched in late October 2022, is roughly 50% complete. An interim, 120-page report (download below) was recently posted to the study’s website. It is curiously labeled as “Draft – Not for Distribution,” which might explain why it was erroneously interpreted as “leaked information,” setting off a flurry of comments. As far as I’m concerned, it’s a public document; therefore, I’m distributing it!

The study’s purpose, according to FRA, is to “evaluate the restoration of daily long-distance intercity rail passenger service and the potential for new Amtrak long-distance routes.” The goal is to “create a long-term vision for long-distance passenger rail service and identify capital projects and funding needed to implement that vision.”

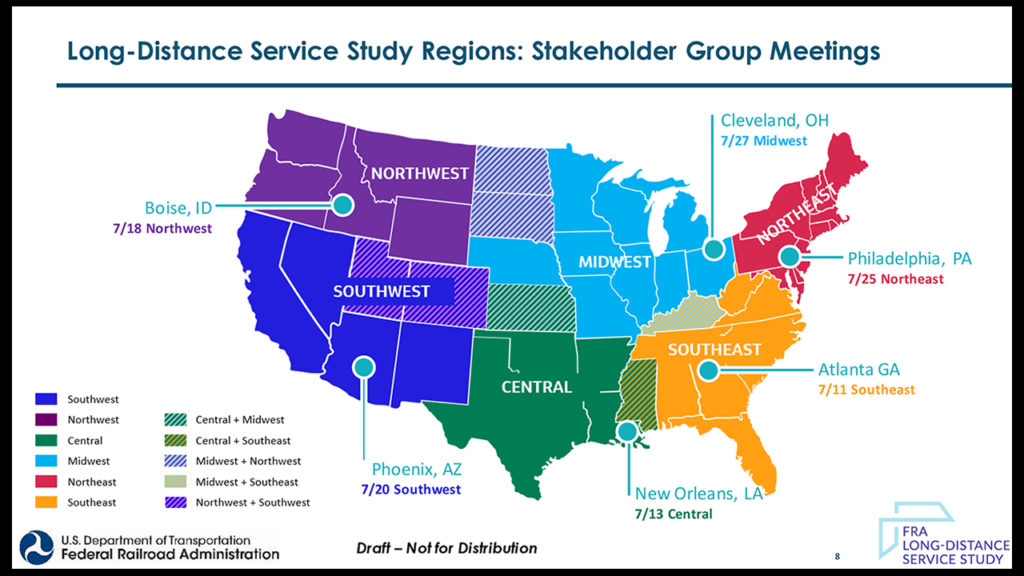

Currently, this study has concluded 6 of 11 “Stakeholder Group Meetings”:

Amtrak has provided an opening statement for each of these meetings:

“At Amtrak, we believe the long-distance and overnight trains are the foundation of our National Network. They are vital to many communities throughout the United States, where in many cases they are the only intercity public transportation service. Long-distance trains also serve many passengers for whom flying or driving is not an option. We want to strengthen and enhance our network. That is why we are moving quickly to use federal funding to refresh and then replace the long-distance fleet and to seek federal grants to improve infrastructure to reduce trip times and to provide additional frequencies to serve more people. The grant applications reiterate our commitment to improving service for all Amtrak customers, from small, rural towns to major metropolitan areas. We are an active participant in the FRA’s LDSS process and look forward to seeing the results of the study. If the FRA’s study recommends expanding the long-distance network, it will require significant federal funding for infrastructure improvements, fleet and ongoing operating support (emphasis mine). We stand ready to work with the FRA and Congress to identify available resources and to determine how to bring more trains to more people.”

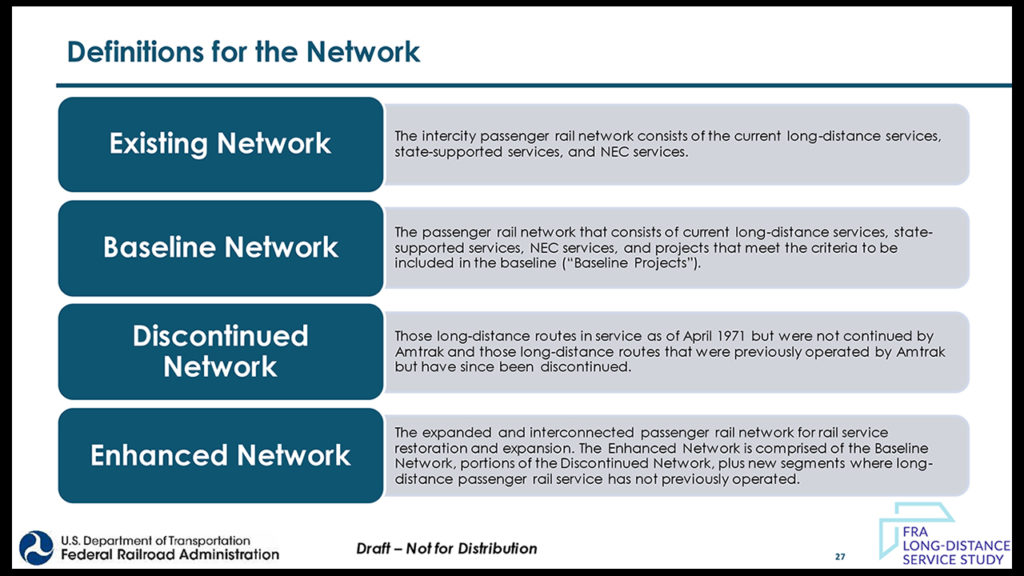

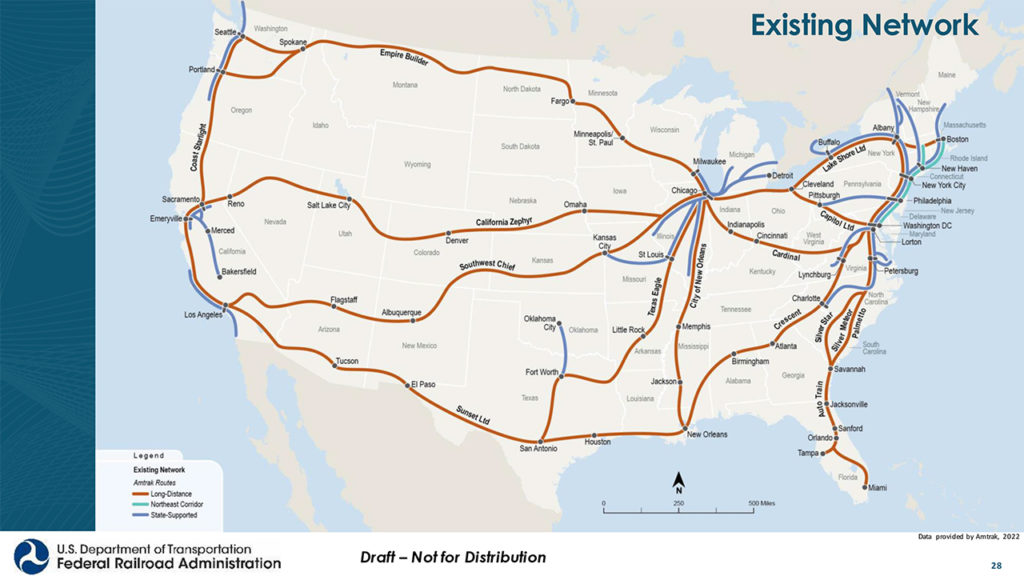

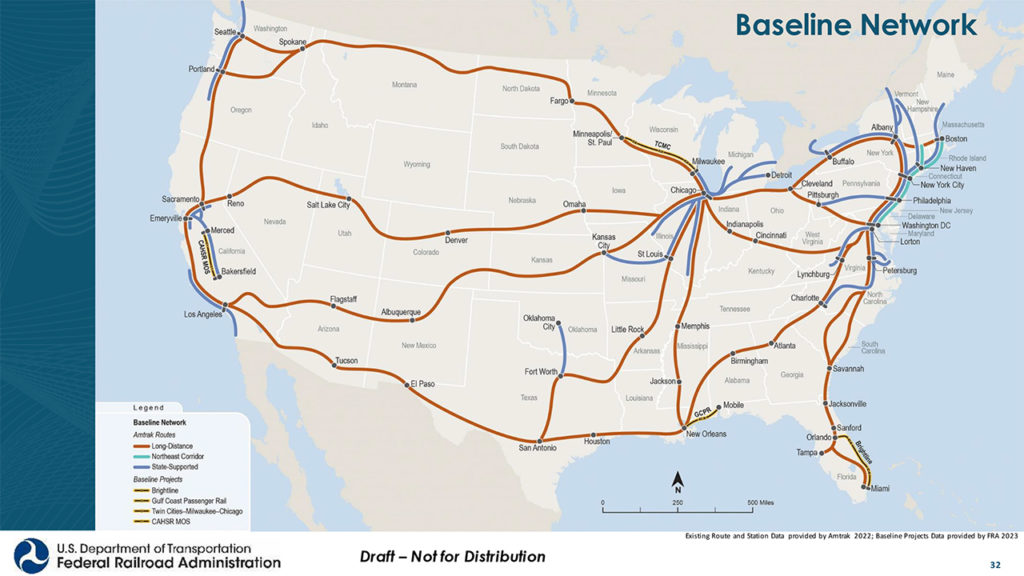

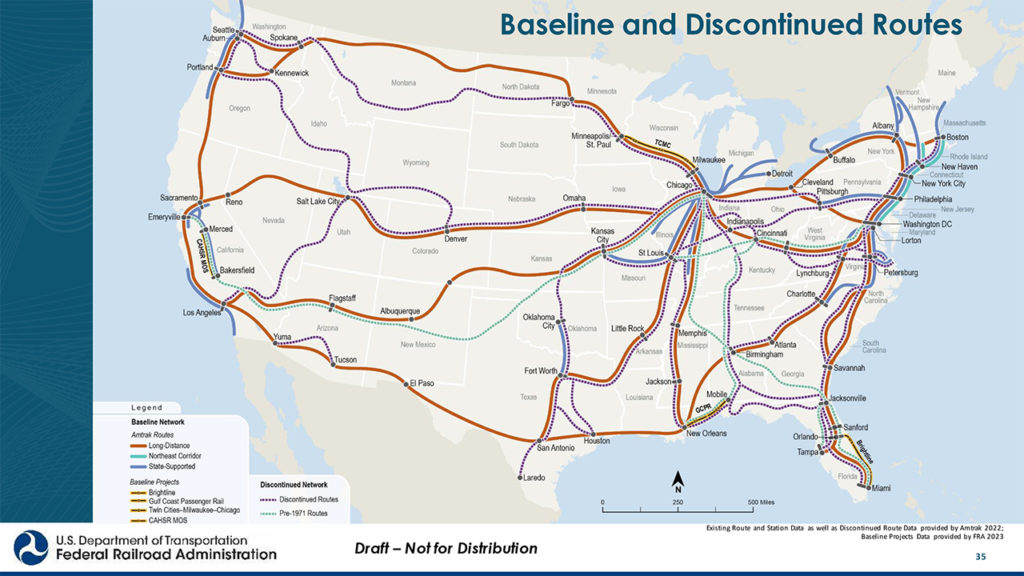

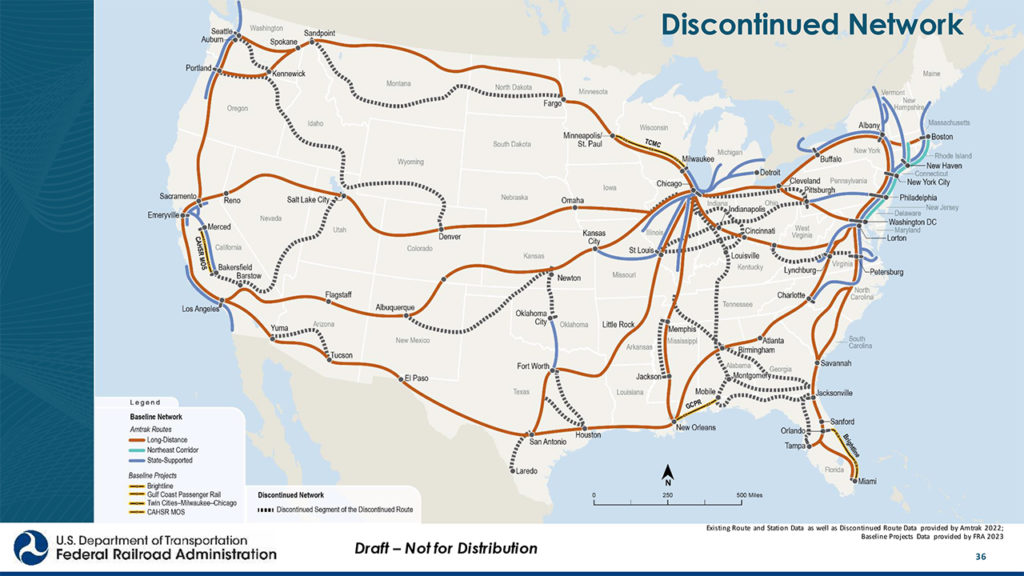

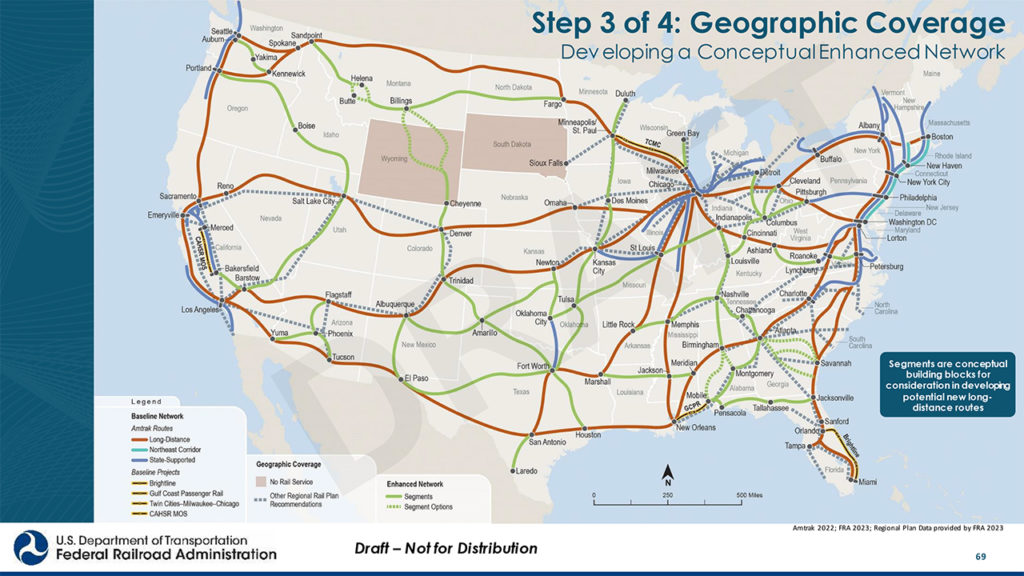

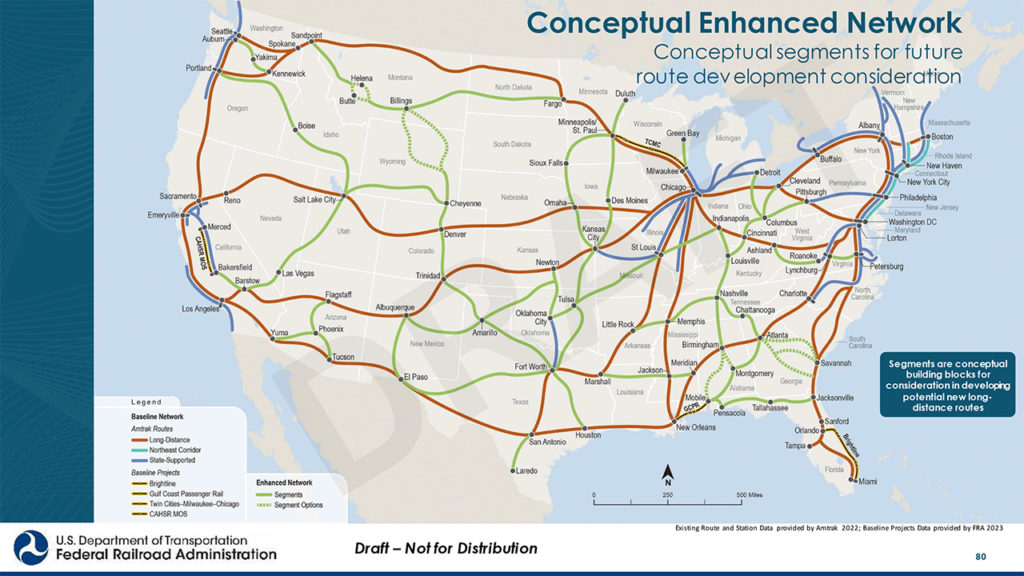

Following are selected maps from the Regional Working Group 2 Meeting report, culminating in a “Conceptual Enhanced Network” in which segments are “conceptual building blocks for consideration in developing potential new long-distance routes.”

Note that the above “Conceptual Enhanced Network” is just that—a concept, none of which is funded. It has been called “Amtrak’s dream map“ by some. Railway Age Contributing Editor and long-time passenger rail advocate David Peter Alan, our resident skeptic, is, well, very skeptical:

“As I said in Railway Age when Amtrak’s Connect US 2035 plan came out, I don’t expect many of these projects to be built, because few of the states will spend the money. As for the long-distance trains, I can make the case that Amtrak is laying a foundation for getting rid of them by attrition, especially since some are already running with a single sleeping car and a single coach. Some of us remember 1969! The paradox I see is that without the long-distance trains, the statute could be changed to have the state DOTs run the trains directly, with an interstate compact if trains serve more than one state. The NEC will keep going as a separate railroad, operated either by a private-sector entity like RAILNet-21 or AmeriStarRail, or by a public-sector entity such as the Northeast Corridor Commission. There would no longer be any need for Amtrak under those circumstances.”

That’s David’s personal opinion; it does not represent the views of Railway Age. I tend to be a bit more optimistic. From my perspective as Editor-in-Chief of this publication, the Conceptual Enhanced Network is a “Field of Dreams Map”: Build it and they will ride. But I’m also a realist. The chances of this grand plan being federally funded, long-term on a grand scale—meaning guaranteed, immune from defunding by the Legislative or Executive branches of government, and enough to build additional infrastructure so host freight railroads are unaffected—are remote.

EXPERT COMMENTARY: LOU THOMPSON

There are people who know a heck of a lot more than I. Prominent among them is Louis S. Thompson, whose long, distinguished transportation career (download his resumé below) includes five years (1968-1973) as a Policy and Budget Analyst in the Office of the Secretary, U.S. Department of Transportation. He was a member of the USDOT team that actually created Amtrak and oversaw the Northeast Corridor Transportation Project. Later, at FRA (1978-1986), Lou was Director of the Northeast Corridor Improvement Project (NECIP). He was also Railways Advisor to the Word Bank (1986-2003). Here’s his take:

We could think of splitting today’s Amtrak into 4 parts:

- A long-haul operator as today that runs the trains and pays for access (including in the NEC). The “national network” would have to be provided with federal support and managed by a national entity (today’s Amtrak?).

- The short hauls for which there would be some federal support as with the commuter operators, but the fundamental responsibility would lie with the state in which it operates. The state can contract with Amtrak to operate the trains if it wishes, or it could make whatever arrangements it wanted. California does exactly this, and it works better than the rest of the Amtrak short hauls. North Carolina and Virginia have done a lot of work in this direction as well. You only get what you pay for (or less).

- An NEC operator that would run the NEC services and pay for access to the infrastructure.

- A joint Amtrak/NEC states entity that would plan, manage and neutrally dispatch the infrastructure.

There are several issues:

- The national network operator would continue to have exactly the same freight interference problems that Amtrak has today. In fact, this will get worse as the Class I’s grow traffic and shrink investment (as they should). This can only be resolved with a lot of money that I don’t see emerging.

- Many states would not elect to run the short hauls if they have to be responsible for them. Also, the Class I’s have fought the idea of anybody other than Amtrak operating intercity passenger trains (better the devil you know …).

- The NEC operator would have to compete for NEC access, so there would need to be some form of federal oversight to ensure that the high-speed access meets regional needs.

- The infrastructure operator would have to operate neutrally in accord with agreed scheduling and dispatching rules. Also, getting agreement on access charges and investment responsibility would be a continuing battle, but what else is new?

- Amtrak has always used the “loose thread” argument, which is basically that their lobbying strength is based on the entire assemblage: Like a sweater, if you pull a loose thread, the whole thing might come apart. This, as we have seen, is a recipe for overcommitment and underperformance.

Above is a short analysis of Class I’s starting in 1978 (the closest year I have to Amtrak’s creation). Look at the yellow cells. Comparing 2021 with 1978:

- (L20) Miles of road excluding trackage rights were only about half (51%) of the 1978 system.

- (L21) Miles of track to miles of road only went up by 6%, so there was no significant improvement of capacity by adding tracks.

- (L22) Miles of road operated/miles of road operated excluding trackage rights went up by 19.9%, so there was an increase in use of trackage rights.

- (L23) Freight train miles/mile of road excluding trackage rights increased more than 70%.

- (L24) Gross ton-miles/mile of road excluding trackage rights increased by almost a factor of 3.

- (L25) Freight train hours/mile. of road excluding trackage rights increased by about 79%.

Bottom line: Since 1978, there is a hell of a lot more traffic out there and it is moving on about half the road-miles. Room available for non-freight traffic is more and more limited, especially for trains that conflict with freight operating speeds. Since a lot of freight is not scheduled, unlike Europe, conflicts with “scheduled” passenger trains are worse than they were in 1978, and as long as current trends continue (both traffic growth and plant shrinkage), it won’t get better.

Given that average freight revenue in 2021 was $196/train-mile, and given that Amtrak pays in the order $5 to $10/train-mile for access (they keep this very confidential), how would you, as a freight executive, view the use of your assets for freight as opposed to passenger traffic? And given these trends, how much sense does it make to propose visionary increases in passenger services over freight lines, especially higher quality in speed or reliability, unless the proposals are accompanied with a lot of money to buy the added capacity and freight buy-in? And if there ever is any actual effort to reduce carbon emissions, would this be the best way to spend our money?

We have 52 years of experience saying that the current approach is not working, so why change?

“Everyone Wants Passenger Trains, But Few Are Willing to Pay for Them”: Karl Ziebarth, Texas Rail Advocates

Class I volume has been declining. But I have the impression that regionals/group operators/short lines/industrial switchers have been increasing volume, partly by taking over unwanted Class I track, partly by increasing service and routes available. Am I wrong?

Of course, everyone wants passenger trains, but few are willing to pay for them.

It seems to me that relatively few freight lines are involved in a meaningful increase in passenger service, and much of it can be on relatively light density lines. No, we are not going to run passenger trains everywhere. And Amtrak/the States/other agencies are going to have to pay for the physical improvements and for clearing bottlenecks.

Lou Thompson is correct in saying that Amtrak pays only a fraction of what high-density freight lines produce. But this ignores that this is the price the Class I’s paid for being relieved of the burden of providing passenger service 1971 (and subsequent years). I have never seen a NPV (net present value) calculation of what that was worth to the Class I’s, but has got to be a lot, based on 1965-70 passenger losses.

So, let’s try to find reasonable solutions to the simple problem. There is a demand for passenger service outside of the NEC. It is bound to lose money. The issue is how to provide the expansion of service that everyone wants with minimum disruption to freight service (which we hope will grow) and at the lowest practical cost.

I am not convinced that Amtrak, as presently set up and managed, can provide that. So let’s work together to develop sensible solutions. For example, other carriers (even Class I’s) might be a much less expensive way to operate—under contract, and with Amtrak’s liability protection—the required service. Use relatively light-density lines for passenger, and permit States and local agencies the freedom to find alternative ways of providing rail service. Face the basic problem of union contracts, which are very restrictive. Everyone must give a little.

Fritz Plous, Corridor Capital LLC: “Dynamite Those Silos”

Amtrak apparently is ignoring some demographic developments that merit train service. Why, for example, is there no proposal for service between Kansas City and Springfield, Mo., and between Springfield and St. Louis? Missouri has metropolitan areas with two million-plus people on opposite sides of the state, connected by a skeletal curriculum of two Amtrak trains a day, but Missouri has a third, smaller but economically important city midway and south between the two, the regional economic center and gateway to Ozarks, Springfield, pop. 670,000. Missouri needs a triangle service with multiple departures throughout the day connecting all three nodes on a schedule permitting easy transfers at the St. Louis and Kansas City nodes. And both sets of trains into Springfield should continue to Branson. The resident population is only 12,883, but the actual population on any given day is thousands higher because Branson is a huge recreational/entertainment destination that can be reached only by car. Frequent rail service would reduce the pressure for parking and give families headed for Branson a chance to enjoy an entertaining ride before they reach their destination.

The BNSF track between Kansas City and Branson continues on to Little Rock. That route would benefit from a through day train as well as a K.C.-Little Rock overnighter for business travelers. This is a classic “too-long-to-drive-too-short-to-fly” corridor. Why isn’t Amtrak or USDOT investigating it? The states involved are too intoxicated with highway-thought to undertake the effort on their own, and Amtrak isn’t paying attention, so who inside of government is supposed to advocate for and eventually fund these needed operations, which don’t fit neatly into Amtrak state-supported-corridor or long-distance categories and thus get overlooked, ignored or dismissed?

Bureaucrats must have their categories before they can act—or even begin—thinking. The division of the nation’s passenger train potential into silos labeled “Northeast Corridor,” “Long-Distance” and “State-supported Corridors” forces (more likely enables) planners to ignore valuable city pairs, triads and corridors that don’t fall neatly into one of the silos.

Another example: Pittsburgh-Columbus-Dayton-Indianapolis-St. Louis. Many advocates have called for the return of the National Limited, which connected these cities with Philadelphia and New York. Great idea, but what about all the people in the intermediate cities who don’t need a trip to a distant end point and who cannot schedule an effective trip when there is only one daily train? The demographics of the former Pennsylvania Railroad route are ideal for corridor service. But the entire five-state distance is too long to qualify as a state-supported corridor, and the shorter distances that do function as corridors cross too many state lines to win coordinated and equitable state support. Look how long it took Illinois and Wisconsin to settle on a 25%/75% split on Hiawatha costs. All the meaningful “corridors” on the route are bi-state or tri-state, and some states, (e.g., Pennsylvania and Missouri) would have very little mileage compared to Ohio and Indiana. So what exactly are the dimensions of the corridor? Is it a Pittsburgh-Columbus corridor? A Columbus-Dayton shuttle? A Columbus-Dayton-Indianapolis corridor? Or is Indianapolis-St. Louis, with no stops at large cities in Illinois, a “corridor”?

If you look carefully at the map, you can see other potential corridors that are being ignored because they do not fit neatly into the “overnight long-distance” or “state-supported-corridor” categories. Planning for a modern, effective system of interactive passenger rail corridors is being neglected, bungled or ignored because the categories force planners to ignore vitally needed connections between important cities.

Back in the 1920s, there was a great public interest in spiritualism, much of it driven by the Russian mystic Nikolai Gurdieff, who fascinated his followers by being able to put himself into a trance at any time without the aid of drugs, flashing lights, music or any other stimuli. As the story goes, a group of psychologists wanted to study Gurdieff to find out just how he managed to put himself into an altered state, so Gurdieff invited them to join him as he launched himself on one of his journeys to “the other side.” Assembled around his bed, they watched him relax, close his eyes and drift off. Just as he appeared to be leaving his earthly surroundings, one of the psychologists leaned over the bed and asked, “What are you thinking right now? What do people have to do to reach the spirit world?” Gurdieff’s breathing grew shallower and shallower, but before he crossed to the spirit world he uttered four little words of advice:

“Think … in … other … categories.”

U.S. passenger rail planners need to heed that admonition and dynamite those silos.