Lehigh Valley Officials Study Passenger Train Restoration

Written by David Peter Alan, Contributing Editor

It has been more than four decades since a scheduled passenger train called at any point in the Lehigh Valley, in northeastern Pennsylvania. At one time the area hosted service to New York and nearby New Jersey, to Philadelphia, and to other places in Pennsylvania, including Reading and Harrisburg. The service to the New York area ended in 1967, to Philadelphia in 1981, and to Reading in 1963. Now, local officials in Lehigh County (which contains Allentown and Bethlehem) have commissioned a study by consulting firm WSP to investigate costs and steps required to restore passenger trains to the area. Study managers and local officials reported to the public about it on March 27.

At a meeting of the convened by Lehigh County officials who sponsored the Lehigh Valley Transportation Study (LVTS), held in person and on line, local officials expressed interested in reviving rail service, but the proposal now under consideration would provide only limited service—running three round trips per day on each proposed and selected line, pegging the start date at 10 to 12 years from now. Angela Watson, Director of Rail, Freight, Ports and Waterways at the Pennsylvania Department of Transportation (PennDOT), likened the ongoing effort to a feasibility study to determine the “potential of likely corridors” in the area. She pointed to the website www.advancingPArail.com, and said that comments on this stage of the study will be accepted through April 12.

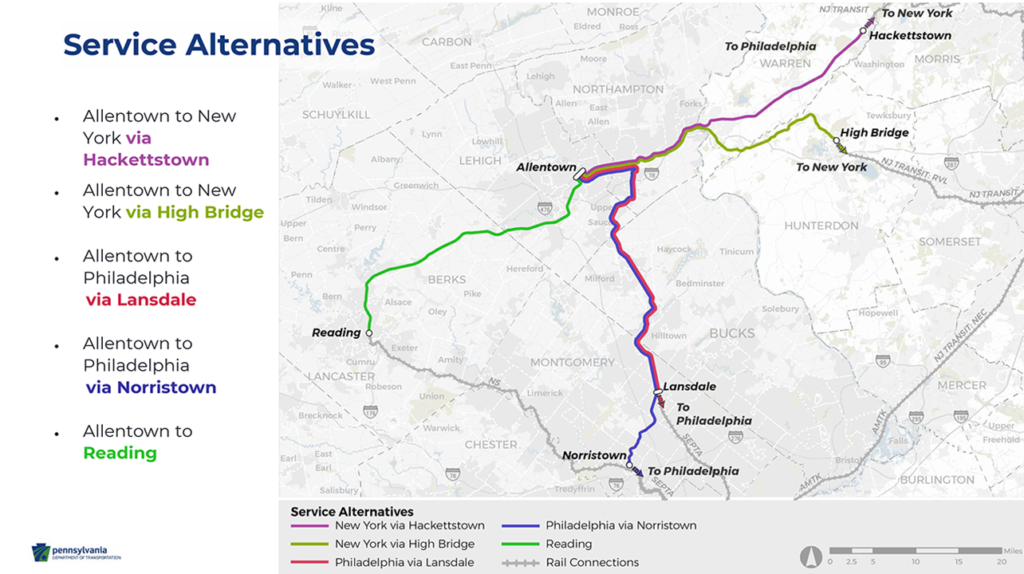

The event was officially called a “Stakeholder Coordination Meeting.” It included public participation and a slide presentation (download below) that described the alternatives for route from Allentown to the New York area, Philadelphia, and Reading. Each of them would require agreements with one or two other railroads from the group consisting of Norfolk Southern, SEPTA or New Jersey Transit. Yet, the study is preliminary and did not include any outreach to those railroads.

The study considered nine candidate corridors, none of which have hosted any passenger trains since at least 1981. The “Corridor Characteristics” considered by WSP included track, structures, right-of-way conditions, operations and environmental screening. There was a comparison of New York and Philadelphia alternatives, in terms of running time and capital and operating costs. The report also considered ridership demand, cost methodology, funding and the project’s timeline, which requires 14 steps before operations could begin.

A 60-page report, the Lehigh Valley Passenger Rail Feasibility Analysis, was prepared by WSP for the Lehigh Valley Planning Commission (a link can be found at https://lvpc.org/passenger-rail, download the study below). The report begins by saying: “The Lehigh Valley Passenger Rail Feasibility Analysis investigates and defines the critical path necessary for restoring passenger rail service to Pennsylvania’s Lehigh Valley, with connections to existing or planned rail services in the Newark/New York, Philadelphia, and Reading market areas. This document (including appendices) summarizes the various efforts to date to restore rail service, identifies the key infrastructure and institutional challenges, estimates costs, defines the necessary approvals and operational requirements, and highlights key steps for both a technical and non-technical audience.”

Where Trains Would Go

WSP is the consultant for the project. Liz Hynes, the project manager for the study, gave an overview of efforts so far. She said that nine potential corridors are under investigation: four to the New York area (including Newark), four to Philadelphia, and a single one to Reading, the former Reading Company line between Allentown and Reading that, about 60 years ago, hosted such trains as the Harrisburg Special and the Queen of the Valley in cooperation with the Central Railroad of New Jersey (CNJ or “Jersey Central”). It is now owned by NS. The study predicts a 46-minute running time, a $450.3 million capital cost, and a yearly operating cost of $2.2 to $4.3 million.

Allentown last had service to Philadelphia in 1979, and service from Bethlehem continued until 1981. Later, about twelve miles of track north of Quakertown had been removed, so restoring service would also require restoring that track, even though much of the former line is now a recreational trail. One of the alternatives for a Philadelphia route would be the old line to Lansdale, where there is full service on SEPTA. According to the study, the running time would be 1:46, the capital cost would be $635.8 million, and operations would cost $5.1 to $10.2 million per year. The other alternative would continue to Norristown and then use the current SEPTA line. The running time would be six minutes longer, capital costs would be $739 million, and operations would cost $5.5 to $10.8 million per year. For each of those Pennsylvania alternatives, the cost of rolling stock is estimated at $102 million.

There are two ways to get to the New York area (service could run into Penn Station with locomotives such as NJ Transit’s ALP-45DP dual-power units). Both routes would use Norfolk Southern’s Lehigh Line as far as Phillipsburg on the New Jersey side of the Delaware River, and the proposed routes diverge from there. It is ironic that, historically, the CNJ connected with the Lackawanna Railroad there at Philippsburg Union Station, and some advocates have suggested that it could again be a transfer point in West Jersey if both lines were to run.

That seems highly unlikely, but both alternatives for serving New York and the New Jersey suburbs have service on NJ Transit today. The more-direct alternative would run on the historic CNJ, which is now NJ Transit’s Raritan Valley Line, at least east of High Bridge. The study projects a running time of 2:20, startup costs of $469.9 million, and operating costs between $16.5 and $20.1 million per year. The other alternative would involve running from Philippsburg over the Washington Secondary to Hackettstown, where NJ Transit service begins. Then, trains could use that agency’s Morris & Essex or Montclair-Boonton Line. Running time is projected for 2:30, with startup costs of $474.9 million and a yearly operating cost of $23.6 to $28.8 million per year. In either case, cost of rolling stock is projected at $145 million. The two lines serve entirely different sets of towns, with the High Bridge alternative serving Central Jersey and the Hackettstown alternative offering two choices serving North Jersey.

The study proposed more alternatives than the ones highlighted; it pieced nine different corridors together. Among the nine segments of railroad (or sometimes ROW without a railroad) mentioned, two of them shown on the map would be operated by agencies other than any potential sponsor for the Lehigh Valley proposal. One is a plan proposed by NJ Transit to restore service between Bound Brook on the Raritan Line and West Trenton, on a historic Reading line, now part of CSX. That service ran on a limited basis until 1982. The other is the segment between Norristown (on SEPTA) and Reading, which lost its passenger trains in 1981. The route was mentioned in Amtrak’s ConnectsUS plan as a potential route for restoration, and the Schuylkill River Passenger Rail Authority is pursuing restoration of the route today.

Where Do We Go From Here?

The study will continue, but the project has a long way to go. There has not been any work on selecting station locations, even though some stations where the proposed trains would run are still intact and located in downtown areas, where most stations were located historically. There have been efforts earlier this century to study some sort of service restoration in the area, with nine studies listed on Page 2 of the report. Six proposed New York service, while the other three proposed serving Philadelphia. They were undertaken by agencies in Pennsylvania or by NJ Transit, all since 2000, and none of them have gotten anywhere. The report described them.

The Conclusion to the report mentioned many more steps, just in the study process. There would be more such action before a passenger train on any of the proposed lines again takes to the rails. The report was detailed in many places, perhaps beyond need. Yet there was no effort to reach out to NS, SEPTA, or NJ Transit, without whose cooperation the proposed services could not run. Bus service in the region is weak,sometimes one trip per day, but buses could provide good connecting links between rail lines, to form an intermodal transportation network for non-motorists and motorists alike.

Brett Webber, an Easton resident and Representative at the Rail Passengers’ Association (RPA), was the only rider-advocate who spoke during the “public comment” period. He mentioned environmental and economic concerns. In response to Railway Age’s question about outreach to rider-advocates, project management said, in essence, that the public could comment. Equating knowledgeable and committed advocates for better train service with the “general public” ignores the knowledge that advocates gain through their efforts, thereby sacrificing a unique and useful resource, as happened with the FRA Long-Distance study.

At least somebody in the Lehigh Valley is interested in having passenger trains again. This study might be the one that starts the process toward some trains coming back eventually, or it could join the others listed on Page 2, sitting forever on the shelf or its electronic equivalent. We will have a personal commentary by this writer about this study and trains in the Lehigh Valley region soon.