VIA Rail Adventures (Third of a Series)

Written by David Peter Alan, Contributing EditorIf there is one “Adventure route” on VIA Rail that is far from the ordinary, it is the train to Churchill, Manitoba. The trip is like nothing offered on Amtrak in the United States, or elsewhere on VIA Rail in Canada. The train takes a long, circuitous journey through a cold, harsh land, going to a town that is unique and, to many visitors, unforgettable.

I had thought for years about taking the train to Churchill but was somewhat apprehensive until I made up my mind that it was time to ride the routes on VIA Rail that I had never ridden before. Going in the summer would spare me the bitter cold that grips northern Canada for much of the year, but there was still the issue of the aggressive bugs that left many visitors with unpleasant stories. There was also the problem I faced on the trip from Toronto to Winnipeg: the lack of food on the train, as I reported in the previous article in this series. That time, though, I can’t blame VIA Rail for class-based prejudice when it comes to food. There were no meals for anybody, whether they rode in a coach or in the sleeping car.

To prepare for the journey, I went to the Forks Market, part of a recently builtreplacement for the old CN freight yard. VIA Rail maintains a passenger yard nearby, but it’s small. I arrived there at 11:00 in the morning on Aug. 8, and bought a hearty lunch of fish and chips, three pieces of fish and more chips than I could finish. That would at least get me started. Then it was time to walk through the back door of Winnipeg Union Station and board the train. It consisted of two EMD FP40H-2 units, a baggage car, two HEP (head end power) coaches from the Canadian fleet built by the Budd Company in 1954 for CP Rail, a “Skyline” car like the ones on the transcontinental Canadian that runs today, and a sleeping car at the rear. When I booked my trip, I was told that the coaches were sold out, so I was required to pay the fare for an upper berth. Riding in it was a unique “once-in-a-lifetime” experience.

Long, Circuitous Journey North

Our train had two different names at times: the Northern Spirit and the Hudson Bay, the name I remember from VIA Rail timetables. It left on schedule at 12:05 PM. It was not crowded, and I spent most of the rest of the day in the dome section of the Skyline car. Like its counterpart in the “economy” portion of the Canadian, it had a lounge section with a few occupants, an attendant below the dome selling drinks and snacks, and six dining tables where hardly anyone ever sat. On its way northwest in Manitoba, the train passed through prairie for hours on end. We came to Dauphin, a sizable town with a beautiful 1912-vintage station, about four hours out from Winnipeg. I explored a bit and found a bakery, but there was not enough time to buy anything without risking missing the train.

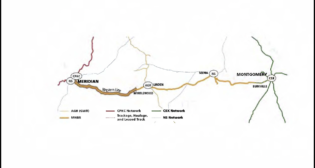

Even though Churchill is geographically east of Winnipeg, the route runs northwesterly to eastern Saskatchewan, then northerly for about six hours in that province, and the rest of the way to Churchill on a northeasterly alignment. The schedule allows about ten minutes of standing time in Canora, Saskatchewan, and I took that time to walk three blocks on Main Street and back to the train. It was the first time that I had set foot in the province, since I have never been to Regina or Saskatoon.

Twilight lingers for a long time that far north in the summer, but there was not much scenery for the evening sun to illuminate. Eventually we ran on track laid on permafrost, land that never thaws, except near the surface. The train moved slowly, and there were few riders in the middle of the trip. I had complained to Colin Sabourin, the Service Manager (VIA Rail had gotten rid of “conductors” many years ago, the person in charge of the train was on the “on-board service” side of the crew). I asked him to help me get the accommodation charge for the first night refunded, since there was plenty of room to stretch out in a coach and I was not informed when I made the reservation that there would be so few passengers riding in the coaches, so there was plenty of room for me. It appeared that he had been successful, so I found a seat configuration that gave me almost as much space as a lower berth, feasible because there were only seven other passengers riding in the two coaches combined.

Throughout the trip, the train made stops at tiny settlements in remote parts of Manitoba. They provided opportunities to get off for a breath of fresh air, and most of those stops included a boarding or two, or an alighting or two. The train provided the only access that the “locals” had to the outside world. That was true for places on both sides of Thompson, the only sizable town north of Dauphin. Much of that part of the trip went through boreal forest, dense woods in cold places that help fight climate change by storing carbon dioxide and keeping it out of the atmosphere.

Thompson is not on the line to Churchill, but at the end of a 30-mile branch running north from Sipiwesk. Our train was the first to stop there in two weeks, due to a freight derailment that knocked the branch out of service. The schedule calls for five hours of standing time at Thompson, from 12:00 noon until 5:00. We arrived shortly after 1:00, which allowed plenty of time to walk into town and buy lunch. I ate in the lunch room at the Ma-Mow-We-Tak Friendship Centre, a community center for the local members of the Swampy Cree First Nation. I had soup and shepherd’s pie, and asked about popular dishes with a “native” flavor. There was one: a bologna and cheese sandwich on bannock, a traditional bread that resembles a biscuit with a very dense texture. I bought one to eat on the train.

The train fills up at Thompson. The highway ends there, so anybody going toward Churchill must get on there. I stayed in the dome section of the Skyline car until it got dark, then retired to my upper berth. It was a unique travel experience, and once was enough for me. In the 1924 song Alabamy Bound, the protagonist longed “to put my tootsies in an upper berth” on his way home to Alabama. Why he preferred that accommodation to a more-spacious lower berth is difficult to fathom. It was cramped, difficult to sit up, and required almost acrobatic contortions to get dressed and undressed. How the old-time “business men” did it wearing suits remains a mystery to me. Still, it was an unusual travel experience, as was the upcoming visit to Churchill.

Unique Town on a Large Arctic Bay

Churchill has more than 300 years of history, founded in 1717 by the Hudson’s Bay Company for its fur-trading operations. The railroad came much later, opening for service in 1930. The train station is the only building in town that can be considered “historic” by most standards. The rest of the town is a hodge-podge of more-recent buildings, connected by gravel streets. There were 870 people living there in 2021, down from a high of about 7,000, when WWII and the subsequent Cold War brought military activity, including a rocket range, to the town. The remaining Churchillians are fiercely loyal to their town, and it exudes a “sense of place” comparable to cities like New York, New Orleans, and Toronto.

Aug. 10 was my day in town. When the train arrived, the town came alive with activity among the locals whose income is based on providing tours for the visitors who just cane in. Many of them focus on seeing unusual animals, particularly beluga whales in the summer and polar bears in the fall. The big white bears wait for ice to form on Hudson Bay, usually in October, and then move onto the ice to hunt seals, their favorite food. They can be seen in town in summer, and a woman with whom I rode on the train reported seeing a “mama bear” and her cub. There are numerous signs warning people not to walk in certain areas, due to the possibility that bear could attack anybody who does so. There is also a “polar bear jail” on the outskirts of town, a building that looks like a big Quonset hut, where unruly or wandering bears are kept after they are tranquilized and until the ice forms in the fall.

Because I only had one day in town, I declined the offers of tours of the area, boat tours to see the whales, and rides on a “tundra buggy,” an apparently homemade vehicle that rides on huge tires and requires a ladder to board. Instead, I decided to spend the day meeting the locals. They liked their town, and they liked the visitors who, to many of them, were potential customers. Penny Rawlings is one member of the town’s business community. She owns the Arctic Trading Company, a rustic-looking store on Kelsey Avenue, the town’s main street. She has operated the business since 1978 and sells locally-made goods and art and craft pieces, like Inuit sculptures. In a promotional video for her store on You Tube, she said: “There’s a real equality of people here. … We treat them [visitors] all the same.”

Churchill has two museums. One is the Itsanitaq Museum, which is affiliated with the local Catholic church and features Inuit art, primarily carvings. Many of those depict the relationships between the people and the animals with whom they interact. The other is located in the trains station and operated by Parks Canada. It’s about Churchill, and most of the exhibits there are about polar bears, whales and other wildlife, and also the history of the town, including the railroad and the former missile range.

Churchill offers many of the necessities of life. The Northern Store is a true general store, carrying food, clothes, housewares, auto supplies, and more. There are a few restaurants serving traditional Canadian (like American) food, and a newly arrived lunch truck that serves Chinese food. The lunch spot favored by many locals for is the cafeteria at the local hospital. The food was decent, and the price was right. There is also a community center, and the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC) has a radio station that carries national programming or Manitoba programs from Winnipeg or Thompson.

My day in Churchill was certainly interesting and, as VIA Rail promotes, unforgettable. It took a long time to get there from Winnipeg, and the route is anything but scenic. Still, it delivered the “adventure” that VIA Rail promised, and the crew was great: Colin the Service Manager, Natalie the Assistant Service Coordinator (comparable to an Assistant Conductor on Amtrak), Mona the sleeping car attendant, and Jessica the lounge attendant in the Skyline car, even though all I bought from her was coffee. They made the trip much more interesting than my previous segment on Train 1 to Winnipeg.

Unexpected Visit to Thompson

VIA Rail had another surprise in store for me, which I learned about when I booked the trip. The Thursday evening departure from Churchill normally goes all the way to Winnipeg but, because of track work, the train was terminating at The Pas. The crew and some passengers would be transferred there to a bus for the rest of the trip. That bus had been filled when I booked, so it was time for Plan B.

The train left Churchill at 7:30 PM, as normally scheduled, and I took it to Thompson and arrived there on Friday morning, about 11:30. I had booked an overnight bus trip to Winnipeg separately, leaving Thompson at 10:00 and arriving at Winnipeg Airport at 7:00 on Saturday morning, where I caught a local bus to go downtown. It was not easy to spend ten hours in Thompson, but I managed it.

The town is relatively new, as is the branch that connects it at Sipiwisk to the line to Churchill. It was founded in 1956 by the International Nickel Company (INCO) to support mining operations in the area. There is nothing older than that, and the town has a rough edge. Even though most of the nickel mines have closed, Thompson survives as a hub for northern Manitoba, providing services for the region.

I returned to the Ma-Mow-We-Tak Friendship Center for lunch. That time I had soup and a Pizza Sub, a sub with ham, pepperoni, cheese and sauce on soft, squishy bread, a local specialty in Manitoba (the news of which has not yet reached New York). Katie, the manager, showed me around some of the town after lunch, as she gave me a ride to the Heritage North Museum. It has two components. One features native animals and plants, the history of Thompson, and remote settlements in the area. The other is a mining museum with equipment from INCO, a replica field office, and other artifacts.

After the museum closed, I walked the Spirit Way: a 2-km (1.2-mile) walking path through the town that highlights its history and culture. It includes various monuments and several depictions of wolves, including a full-wall mural of a wolf on one of the town’s largest apartment buildings. After a light dinner at another local restaurant, the bus station opened, so I waited there for the bus. The trip was fast, a straight shot on the highway that took only nine hours. Because of the nature of the track and the circuitous nature of the route, the train is scheduled to take 26 hours to travel between those two points. In effect, because I spent ten hours in Thompson and took the overnight bus, I was able to spend Saturday exploring Winnipeg. I arrived downtown by 8:30 AM, eight hours ahead of the train schedule.

Winnipeg Weekend

Manitoba’s only city of any size is Winnipeg, which is also the provincial capital. I found the downtown area to be a truly mixed bag, with beautiful buildings sprinkled among newer and less-interesting ones, empty space, some mean streets, and an environment that was not particularly friendly toward pedestrians. There is a good local bus system there, but no rail transit. There is also the cold. Some locals call the city “Winterpeg” because it is the coldest major city in North America, and winter lasts a long time. I chose to visit in the summer, so the weather was pleasant when I was there.

The beautiful buildings in the city seemed isolated, as if they were placed randomly. The entrance to Union Station, which hosts trains going in three directions but only twice per week, is majestic. So is the Fort Garry hotel across the street, a 1913 gem built by the Grand Trunk Railway, which later became part of CN. I stayed at the one-year-younger Marlborough, which retains a few traces of its fading glory, but has fallen on harder times lately. That seems to demonstrate Winnipeg’s contrasts.

Downtown Winnipeg is not a pedestrian-friendly place. Many of the sidewalks are not in a state of good repair. Portage and Main, the city’s principal intersection (known as the windiest corner in Canada) has barriers to prevent pedestrians from crossing the street without walking a block out of the way or using an underground passageway. There is also the Exchange District. a part of downtown featuring beautiful commercial buildings from the early 1900s, which evoke a strong sense of heritage.

In addition to the Exchange District, I spent time in two neighborhoods on the other side of the Red River from downtown: St. Bonifice and Fort Rouge. The former is a Francophone neighborhood with a strong sense of tradition, while the latter is an unremarkable, but attractive, century-old residential neighborhood. Winnipeg has museums and other attractions, too, including the Canadian Museum of Human Rights, a good place to spend a day receiving a powerful and moving educational experience.

At noontime on Aug. 12, it was time to leave Winnipeg and begin the journey to the train once known officially as the Lake Superior. Today it is known by railfans and locals in parts of Northwestern Ontario as the “Budd Train” because it is the last-remaining scheduled train that runs with Rail Diesel Cars (RDCs) built by the Budd Company during the 1950s. It was not easy to get from Winnipeg to White River, where the train originates. I will report on the Budd Train, and the segments that got me from Winnipeg to White River and, later, east from Sudbury (at the other end of the Budd Train’s route) to Ottawa in the next article in this series.

David Peter Alan is one of America’s most experienced transit users and advocates, having ridden every rail transit line in the U.S., and most Canadian systems. He has also ridden the entire Amtrak and VIA Rail network. His advocacy on the national scene focuses on the Rail Users’ Network (RUN), where he has been a Board member since 2005. Locally in New Jersey, he served as Chair of the Lackawanna Coalition for 21 years, and remains a member. He is also Chair of NJ Transit’s Senior Citizens and Disabled Residents Transportation Advisory Committee (SCDRTAC). When not writing or traveling, he practices law in the fields of Intellectual Property (Patents, Trademarks and Copyright) and business law. Opinions expressed here are his own.