Does the AAR Fear Competition?

Written by Frank N. Wilner, Capitol Hill Contributing Editor

How remarkable that the customarily staid Association of American Railroads (AAR) is following a Marx Brothers comedy script to derail a Surface Transportation Board (STB) proposed rulemaking intended to assure railroad competition. One scene violates first-year law school advice not to irritate judges hearing your case; another vandalizes economic science by comparing a highly competitive soft drink market with rail service monopolies.

The rub is that independent, narrowly focused, expert regulatory agencies such as the STB do not respond well to hysterical mob strategy as is being employed by the AAR—it being more suited to sway popularly elected legislators.

The STB’s role is to regulate railroad rates and practices by focusing on the law, economic science and precedent rather than in response to petition drives or entreaties of rail-friendly third parties mimicking marchers bearing picket signs and bullhorns.

This injudicious AAR scheme has enlisted a squad of acquiescent front groups preaching a variety of questionable and beside-the-point arguments ostensibly to dissuade the STB from fully administering a partial economic deregulation statute that railroads pursued, helped author and gleefully accepted four decades ago (the 1980 Staggers Rail Act). A now-inconvenient provision instructs regulators to establish procedures for “maintaining reasonable rates where there is an absence of effective competition.”

More farcical, the AAR is leveraging a quantity-has-a-quality-of-its-own strategy with an invitation to cyber surfers—subject comprehension unnecessary—to sign an on-line petition urging the STB to ignore its statutory duties.

Reality is that Congress, when partially deregulating railroad rates and practices in 1980, intended to preserve competition where shippers lack effective transportation alternatives to rail. Shipper appeals for that statutory protection became more acute following a tsunami of post-1980 rail mergers that reduced effectual freight transportation to just one railroad at many shipper loading and unloading facilities.

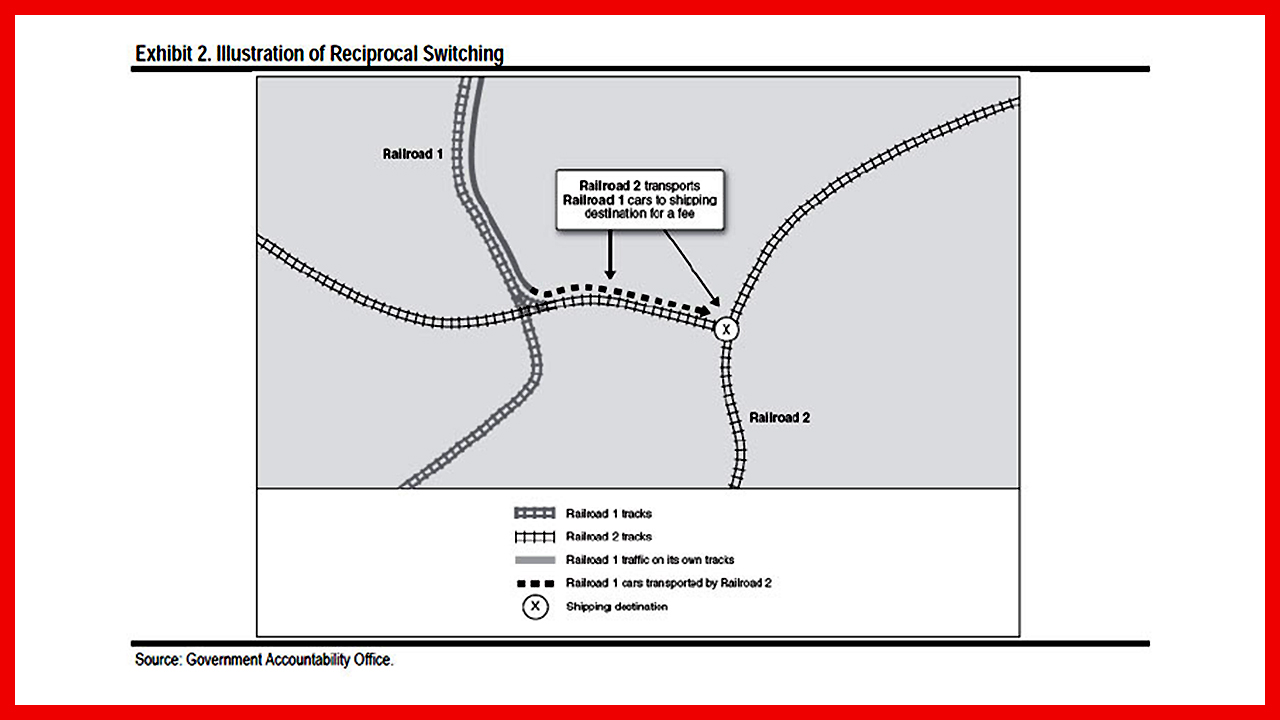

One remedy—that Congress in 1980 specifically granted the STB to impose—is to accord shippers captive to a single railroad access to a second railroad through Reciprocal Switching.

Reciprocal Switching means that in limited circumstances, a shipper served by only one railroad at origin or destination may request its freight cars be switched to or from a second, nearby railroad so as to create price and service competition over the longer line-haul. The second railroad would pay a compensatory switch fee. The Reciprocal Switching remedy would have to be “practicable or in the public interest” and “necessary to provide competitive rail service.”

The expectation of a Reciprocal Switching mandate is that with the prospect of two-railroad competition for the line-haul, the railroad holding sole access to the shipper loading or unloading facility would provide a more competitive price and service so as to retain its single-line origin-to-destination haul.

That expectation has been unattainable by shippers as STB predecessor Interstate Commerce Commission—in a case known as Midtec—created what shippers consider an insurmountable evidentiary burden requiring them to prove a railroad was engaging in, or is likely to engage in, market power abuse or anticompetitive conduct as a requisite to obtaining a Reciprocal Switching remedy. That hurdle spawned the current rulemaking and its less restrictive evidentiary showing.

Shippers recall an unrelated rulemaking in 1998 where shipper attorney Edward D. Greenberg explained how railroads use evidentiary hurdles to delay and frustrate shipper petitions for regulatory relief. A railroad, Greenberg said, demanded of his shipper client a “list of all customers, every conceivable end use of the products shipped, and the products manufactured from them.”

It is ironic that while railroads term Reciprocal Switching “forced access” (shippers term it “competitive access”), it is railroads, through mergers, that eliminated multi-railroad competition and now complain that restoration of just two-railroad competition on a limited basis is somehow anti-competitive.

In furtherance of this shipper-proposed remedy, the STB will hold a two-day hearing March 15-16 on a rulemaking named “Ex Parte No. 711 (Sub-No. 1), Reciprocal Switching.”

AAR-generated opposition to this proposed rulemaking is overstated. Reciprocal Switching is not, as the AAR asserts, akin to Coca Cola being required to allow Pepsi to produce and bottle soft drinks at a Coke facility. A Reciprocal Switching mandate would be imposed only where a railroad holds a monopoly at an origin or destination shipper facility. The shipper requesting Reciprocal Switching would bear the evidentiary burden that Reciprocal Switching is feasible and necessary to enhance competition.

Reciprocal Switching has been in use in Canada for more than a century (known there as “Interswitching”). On a voluntary basis, a form of Reciprocal Switching exists in St. Louis (St. Louis Terminal Railroad Association); Chicago (Belt Railway); and in Northern New Jersey, the Philadelphia area and Detroit (Conrail Shared Assets).

Impressively, railroad legend E. Hunter Harrison didn’t consider Reciprocal Switching “as universal railroad Armageddon,” wrote Railway Age Editor-in-Chief William C. Vantuono. In 2015, Vantuono quoted Harrison—then Canadian Pacific (CP) CEO—that Canada’s Interswitching law is “one of these regs that are in place, but people don’t really take advantage of it, because there’s no need to if the individual carriers do their job. If we do not provide the service, we should not be resistant to someone else coming and providing that service.”

A 2013 study by Highroad Consulting found that following the adoption of Interswitching in Canada, CP and CN posted increased freight revenue and profits while improving service levels.

Rhetorically, were Reciprocal Switching as operationally inefficient as the AAR asserts, why would a shipper want it? In fact, nearly a century ago, in an era of low technology, six railroads interchanged traffic over the historically celebrated “Alphabet Route” linking New York, Philadelphia and Baltimore with Chicago, and successfully competed with the single-line efficiency of railroads Baltimore & Ohio, New York Central and Pennsylvania.

As proposed by shipper group National Industrial Transportation League, a Reciprocal Switching remedy would require the following showing:

- The shipper (or group of shippers) is served by a single Class I railroad.

- There is no effective intramodal or intermodal competition for the movements for which Reciprocal Switching is sought.

- The rate for the movement has a revenue-to-variable-cost ratio of at least 240%, or the incumbent railroad over the past 12 months has handled 75% or more of the transported volume at issue.

- There is, or can be, “a working interchange” [junction point] between a Class I carrier and another carrier within 30 miles of the shipper’s facility.

- Reciprocal Switching is safe and feasible and would not unduly hamper the carrier’s ability to serve existing shippers.

Railroads do have a legitimate question as to whether competition would be enhanced in all cases through Reciprocal Switching. Although the Justice Department, in comments filed with the STB, said that “the proposed [Reciprocal Switching] rule provides a judicious way to improve the competitive options for captive shippers,” it cited “a well-established principle in economics that a small number of competitors may be able to coordinate, either explicitly or tacitly, to charge higher prices than would arise” in a more competitive market. The reference is to economic theory that a minimum of three competitors (not just two) is required to assure a competitive result.

However, another economic theory holds that duopolists do compete. A 2004 Brookings Institution working paper concluded that after Union Pacific (UP) gained equivalent access as BNSF to Powder River Basin coal shipments, the two railroads effectively competed on price and service.

John Hood, a former president of the free-market John Locke Foundation who has written for numerous other free-market think tanks, including the Heritage Foundation and Reason Foundation, wrote recently that “competition usually drives cost down and quality up. Its absence usually leads to trouble.”

Competition is not a race to the bottom. Consider that when UP and Southern Pacific merged in 1996, eliminating two-railroad competition for many shippers, UP-SP voluntarily granted BNSF access to some 4,000 miles of UP-SP track to restore two-railroad competition. Both railroads subsequently improved profitability and service quality.

In 1998, when CSX and Norfolk Southern raised some $12 billion to purchase Conrail, they did so with investors aware that the two intended voluntarily to create Conrail Shared Assets to provide former Conrail shippers with two-railroad access via Reciprocal Switching.

Moreover, railroads are not suffering an earnings squeeze. Investment savvy conglomerate Berkshire Hathaway, which in 2010 acquired BNSF for a $22 billion premium above market value, reported in February that for COVID-affected 2021, BNSF recorded record earnings of almost $6 billion after accounting for interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization.

Revenue adequacy is defined by the STB as having earnings sufficient to cover total operating costs, including depreciation and obsolescence, plus a competitive return on invested capital sufficient over the long term to attract capital to maintain a railroad’s large and costly infrastructure, including locomotives and rolling stock.

Further evidence of railroad financial strength came in September 2021 when STB Chairman Martin J. Oberman, citing railroad-supplied data, said that since 2010, Class I railroads have delivered to shareholders “more than an astounding $183 billion in buybacks and dividends.”

Try as the AAR might to spin the issue of Reciprocal Switching into a redux of the 1935 Marx Brothers classic, “A Night at the Opera”—where Chico and Groucho serially shred a contract because “whatever it is, I don’t like it”—expect the STB at its March 15-16 hearing to play the role of television’s fabled no-nonsense police detective Sgt. Joe Friday (“Dragnet”) who demanded always, “Just the facts.”

Railway Age Capitol Hill Contributing Editor Frank N. Wilner is a former assistant vice president for policy at the Association of American Railroads, a former White House appointed chief of staff at the STB and a former president of the STB bar association. Among his seven books is the pending publication of “Railroads & Economic Regulation.” He has written also for the free-market focused Heritage Foundation and Cato Institute.