Jurisdictional Jumble

Written by David Peter Alan, Contributing Editor

Shutterstock/Nicole Glass Photography

RAILWAY AGE, AUGUST 2023 ISSUE: WMATA operates under an overly complicated structure that intertwines it with politics far more than other transit providers.

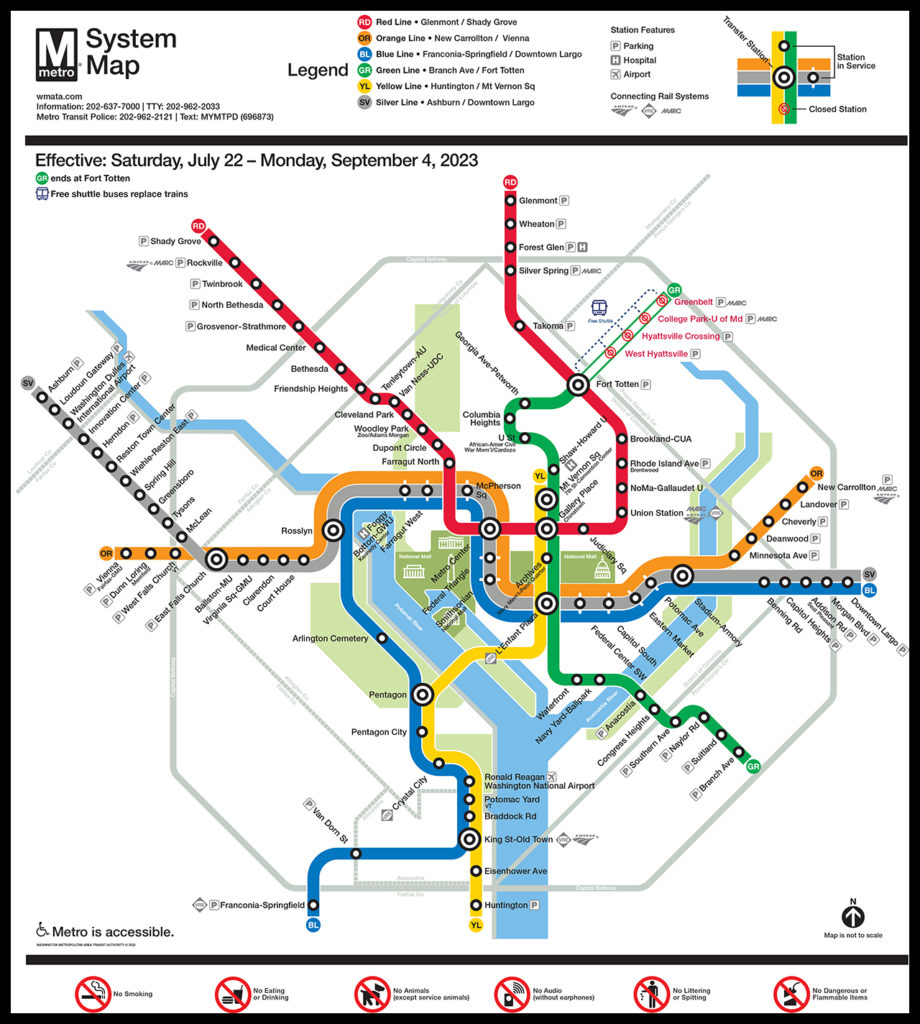

Fifty years ago, the streets of Washington, D.C. were torn up for construction of the Metrorail system. Today, that system consists of six color-coded lines, the original five plus the new Silver Line that includes a stop for Dulles Airport and extends further into northern Virginia. It serves three jurisdictions: the District of Columbia itself, nearby parts of Maryland, and northern Virginia. On top of that, the federal government acts as a fourth jurisdiction to which the agency must answer.

While transit everywhere in the nation is embroiled in politics, the Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority (WMATA, commonly known as “Metro”), which includes Metrorail, operates under a structure that intertwines it with politics more than other transit providers. The District of Columbia Home Rule Act, which established an elected city-style government for the District, went into effect at the end of 1973, in the middle of Metrorail construction. WMATA was established by an interstate compact that had been approved by the legislatures in Maryland in 1965 and Virginia in 1966. Under the Compacts Clause of the Constitution, Congress must also approve all interstate compacts, and they did so later in 1966. WMATA was founded on Feb. 20, 1967.

The new authority succeeded the National Capital Transportation Agency, which was founded in 1960. That agency had proposed an 89-mile rail system, but highway advocates got the proposal reduced to only 23 route-miles. Then came the Urban Mass Transportation Act of 1964, which promised federal funding for building transit projects and founded the Urban Mass Transit Administration, the predecessor to today’s Federal Transit Administration (FTA). The Act also served as the impetus for forming WMATA.

Construction began in 1969, and the first segment opened for service on March 27, 1976. It consisted of five stations on the Red Line, from Farragut North to Rhode Island Avenue. That segment included Union Station, the home of Amtrak and local commuter trains, of which there were few at the time. Over the years, the Red Line was completed, and the Blue, Orange and Yellow Lines were built. The Green Line, which serves the Southeast quadrant of the city, came later, and was completed on Jan. 13, 2001. That event also marked the completion of the original 103-mile, 83-station system. There have been a few infill stations added since that time, as well as the Silver Line in northern Virginia, which opened in two segments: to East Falls Church in 2004, and to its current terminal at Ashburn with a stop at Dulles Airport in 2022. The newest station is Potomac Yard in Alexandria on the Blue/Yellow line (below).

The original interstate compact that formed WMATA was only concerned with rail. Although we are concerned with the rail system in this article, other transit in the nation’s capital is subject to the same political pressures as Metrorail. The compact was amended in 1971 to allow the authority to operate buses, and today it operates an extensive bus system, as well as paratransit. The D.C. city government operates the 2.4-mile streetcar line on H Street and Benning Road, which opened for service in 2016 and was the first streetcar in the District since 1962.

Politics in Play

As a general premise, it is impossible to write about passenger trains or transit in the U.S. or Canada without considering politics. Rail transit is part of the public sector wherever it runs. It depends on government, especially for funding, which means politics. All transit agencies must deal with the governments, including the elected officials in the states where they run, but WMATA is different. It is situated under the direct control of the District, as well as Maryland and Virginia, and overlaid with the authority of federal instrumentalities like Congress and the Department of Transportation (DOT) with its sub-agencies like the FTA.

That level of political control is embedded in the agency’s structure. Its Board of Directors consists of two voting members and two alternates each from the District of Columbia, Maryland, Virginia, and the federal government, the latter appointed by the Secretary of Transportation. D.C. government or state authorities appoint the other members and alternates. The chair rotates among the three non-federal jurisdictions, and the Board appoints Metro’s General Manager, but only the Board as a whole can give any instructions or supervise the General Manager or any of the agency’s other employees.

In theory, this looks like a sensible and equitable system, because many of the region’s residents and employees move freely on Metrorail between the three jurisdictions. In a sense, the District is a city whose suburbs happen to be located in different states. The situation would be analogous to what is now New York City being a separate city-state, with New Jersey and the rest of New York State containing all the city-state’s suburbs and smaller cities within their borders. Below the surface, partisan politics rears its head, and a look at current politics in the region would be instructive.

The District of Columbia (the actual capital city) is a stronghold for Democrats. Even when only one other state voted for that party in the 1972 and 1984 elections, so did the District. That won’t change anytime soon.

Democrats have also dominated Maryland politics for the past 150 years, except for a few brief periods. It appears that Marylanders’ political views have changed with the party’s platforms. The state has had only two Republican governors since Spiro Agnew (1967-68), one of whom was Larry Hogan (2015-22). Hogan had pushed the Purple Line, a light rail line in the D.C. suburbs, which would connect with Metrorail and add extra transit links on the Maryland side of the region. Democrats held most of the other offices in the state, especially in Baltimore. Some local advocates in that city accused Hogan of favoring suburban areas over their city, especially since he did not support the proposed east-west Red Line rail project there. The current governor, Wes Moore, is a Democrat and a Baltimorean. He supports the Red Line project, has called for other transit in the state and, according to a report in Maryland Matters, mentioned when he was campaigning that he and Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg were classmates at Oxford.

Virginia has gone in the other political direction lately. Republican Glenn Youngkin was elected governor in 2021, and his party captured the House by a slim margin. Ralph Northam, who preceded him, is a Democrat whose party had carried the House and Senate in 2018 and still holds a slim lead in the Senate. The state had been dominated by Democrats until the 1960s, when it turned Republican as part of Richard Nixon’s “Southern Strategy” in response to desegregation in the South. Current Democrats, whose policies are different from those of the pre-1960s party, have made gains in Virginia since 2000, establishing it as a “purple” state.

Northern Virginia, where Metrorail operates, is a stronghold for the Democrats, as are cities like Richmond, Norfolk, Charlottesville and Roanoke. Republicans dominate in the more-rural southern and western parts of the state. The only rail transit in Virginia, except for Metrorail, is The Tide, a light rail line in Norfolk. There are also “peak-hour” trains for commuters living along lines from Washington, D.C. to Manassas and Fredericksburg on Virginia Railway Express (VRE). During the Northam Administration, the Virginia Passenger Rail Authority announced plans for purchasing rights-of-way from CSX and NS to bring more passenger trains to the state and expand local rail. So far, the Youngkin Administration has not disturbed that program.

The situation in Congress is unsettled. Now that Republicans have won the House, they have proposed a budget that would slash funding for Amtrak. Democrats still hold the Senate, so the actual results remain to be seen. So does funding for transit projects, although money for capital projects under the Infrastructure Innovation and Jobs Act (IIJA), also known as the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (BIL), is still being spent. The big question is what will happen to transit, including Metro, when the federal money from the COVID-19 relief legislation for the operating side runs out during the next year or two. That event has the potential to cause catastrophic damage to transit everywhere in the nation.

Metrorail Challenges

Even without the influence of politics, the past few years have been difficult for Metrorail. These difficulties have been reported by commentators concerned with government, in popular media and here at Railway Age.

Jake Blumgart reported a litany of Metrorail’s problems on June 30, 2022 in Governing. He led off by saying that Metro’s situation with three jurisdictions is problematic: “With authority and accountability split between three jurisdictions, the nation’s third-largest transit system has lurched from one crisis to another. Now, with ridership and reliability tanking, the service faces an uncertain future. In the past half-year, Metro’s service has spectacularly fallen apart. A confluence of mishaps, scandals and regulatory scrutiny has engulfed it as WMATA faces the worst fiscal crisis in its recent history.”

As part of that litany, Blumgart mentioned Metro’s deficit due to decreases in ridership (a problem shared by other transit agencies), a derailment that forced the 7000 Series railcars out of service, agency disregard for workers’ safety, and a “culture that accepts noncompliance“ with rules. He also mentioned several specific accidents and other incidents that occurred on Metrorail over the years.

Safety was such a problem at Metrorail that the FTA exercised its newly acquired jurisdiction over safety for the first time at the agency in 2015.

Metrorail’s problems have been reported in the popular media, too. As far back as April 26, 2016, a headline on National Public Radio (NPR) asked the question: “At A Time of Near-Constant Bad News for Metro, Why Has the WMATA Riders’ Union Gone Silent?” The situation does not appear to have gotten better. On June 11 of this year, Jordan Pascal and Olivia Guyapong of local NPR station WAMU reported a story on the network with the headline: “Metro May Look to Service Cuts and Fare Increases as it Faces $350 Million Budget Gap.” They reported: “Higher fares and less service are going to be tough for riders to swallow, local Metro watchers say. Riders have already expressed frustration because they’re currently paying peak service fares while waiting 10-30 minutes for a train.” They also quoted Stephanie Gadigbi-Jenkins, a Metro Board member from the District, as saying, “It’s going to be important for the leadership in each of the jurisdictions to think about how to ensure that there’s sustainable funding for Metro in the long term … and how to also meet the needs of riders.” That might be the ultimate challenge for elected officials, but “can they meet it?” is the big question.

Back to the question: Are there too many jurisdictions, including Congress?

Blumgart blamed Metro’s multi-jurisdictional situation for many of its problems: “From the beginning, WMATA has been dogged by questions of authority and accountability. Although many transit systems cross state lines, there is usually one major stakeholder. At Boston’s MBTA, the Massachusetts governor is ultimately responsible. In New York City’s MTA, all roads lead to Albany. At WMATA, there is no single leader who can be held responsible. Virginia, Maryland, the District of Columbia and the federal government all share responsibility, which often means no one does.”

These concerns still haunt the agency. As recently as July 20, a Washington Post editorial headlined “Metro’s Countdown to Fiasco is Under Way in the D.C. Area” sounded the alarm: “Unless unresponsive regional leaders act soon, with significant additional aid from Congress, subway and bus commuting times will likely triple or quadruple, and train and bus service would halt at 9:30 p.m. Three in five subway trains would be removed from service, as would nearly seven of 10 bus lines. That would drive away transit passengers, worsen rush-hour traffic jams and strike a lethal blow to the downtown core’s hopes for post-pandemic revival and the region’s prospects for long-term prosperity.” The paper chided D.C. Mayor Muriel Bowser and Govs. Youngkin and Moore for not working out what it described as “a politically painful and costly fix,” and warned: “Metro’s looming problems—a perfect storm of issues that spell the end of transit service as the region has known it starting next summer—will not resolve themselves.”

Reasons For Hope?

Metro is looking toward the future, as agencies always do, regardless of circumstances. Tara Suter reported in The Hill on July 10, that Metro had unveiled its expansion plans: “Implementation of one of the six new proposals, designed to deal with a capacity increase on the transportation system, could cost anywhere from nothing to about $50 billion and could take up to 10 to 20 years to complete, according to officials.” Her report contained a link to a WMATA report dated July 13 about a capacity study for the Blue, Orange, and Silver Lines. The report suggested rail options that include running the Blue Line to Greenbelt or to National Harbor, a Silver Line Express in Northern Virginia, and running the Silver Line to New Carrolton. Suter also reported, “Metro is also headed into its next financial year with a $750 million operating deficit. Officials said the possible expansions, however, are necessary to increase system reliability.”

The big question remains whether politicians in four jurisdictions can get together and come up with a means for giving enough money and sufficiently good advice to a transit system on which their constituents depend, in time for that money and that advice to do any good. New York City’s transit was in terrible shape in the early 1980s when the late Richard Ravitch (later Lieutenant Governor) and state officials came up with a plan that kept the subways going and allowed subsequent improvements. Today’s situation is different, with the COVID-19 relief money running out in a year or two, with potentially catastrophic results for transit agencies and riders everywhere.

In their WAMU/NPR report, Pascal and Guyapong urged listeners to remember the recent past: “Think back to November 2020, when Metro faced a $500 million pandemic-induced budget deficit. Metro officials proposed drastic cuts, including shuttering 19 stations, eliminating weekend service, laying off 2,400 workers, and [reducing train service to] every 30 minutes. Months later, the federal government came in with relief funds to save the day and avert a crisis.”

It’s unclear whether a similar result could happen today, with several jurisdictions that don’t always “play well together.” Time will tell, and soon.

Potomac Yard Station a Model of Sustainability

The new Potomac Yard Metrorail Station opened in Alexandria on May 23, serving Metrorail’s Blue and Yellow lines. “The sustainably designed station demonstrates the vitality of rail transit for commuters,” says lead designer Arup. “It fosters sustainability through its thoughtful design and its encouragement of high-density urban growth and low-carbon travel.” Arup provided structural, mechanical, engineering, plumbing, civil, fire and geotechnical engineering, as well as information technology and communications, sustainability, and security consulting and lighting design in support of Potomac Yard Constructors, the Halmar-Schiavone Joint Venture, and WMATA.

Previously the largest railyard on the Eastern seaboard, Potomac Yard has undergone redevelopment over the past few decades. The addition of the new station, which is located between Ronald Reagan Washington National Airport and the Alexandria, “will be key to catalyzing the development of the surrounding area into a walkable urban hub,” notes Arup. “Bordered on one side by wetlands and on the other by freight rail, the station is connected to the adjacent neighborhood by a pedestrian bridge at the north end. We designed the bridge to provide foot and cycle access over the freight rail corridor to the station pavilions, linking in with the adjacent Mount Vernon Trail and promoting sustainable mobility over car traffic. Our team also oriented the south entrance pavilion to be more accessible for the sight-impaired traveling to and from the National Industries for the Blind, located across Potomac Avenue from the station. In the coming years, the station is expected to generate billions of dollars in new private sector investments, eventually supporting 26,000 new jobs and drawing 13,000 new residents to the burgeoning mixed-use community.”