VIA Rail Adventures (First of a Series)

Written by David Peter Alan, Contributing EditorAt 6:15 PM Eastern time on Friday, Sept. 1, 2023, I achieved a milestone in my “career” of riding trains. As VIA Rail Train 601 rolled into Jonquiere, Quebec, I completed the adventure of riding the entirety of every route now operated by Canada’s railroad. There are a few more passenger trains in that country: trains to remote places running on railroads owned and operated by First Nations tribes, as well as a few tourist railroads like the historic White Pass & Yukon route. But there aren’t many such trains, and VIA Rail runs most of the few passenger trains in Canada, much like Amtrak runs essentially all non-local passenger trains in the United States.

VIA Rail was formed in 1977, for many of the same reasons why Amtrak was founded in 1971. When Railway Age reported on Amtrak’s 50th anniversary, we recalled how nearly two-thirds of U.S. intercity passenger trains that left their points of origin on April 30, 1971 did so for the last time that day. That was not the case with VIA Rail. The Canadian National (CN) and Canadian Pacific (CP) railroads did not run many passenger trains by the late 1970s, and VIA Rail kept many of them going in the early days. There were cuts, like the train to La Malbaie, Quebec, which bit the dust shortly after VIA Rail took it over from CN. Today, it runs seasonally as the Train de Charlevoix, a tourist railroad.

Until 1981, passenger trains ran daily along the CN and CP mains between Vancouver on one end, and Toronto and Montreal on the other. The Toronto and Montreal sections joined and split at Sudbury on CP’s Canadian and at nearby Capreol on CN’s Super Continental. The “Super Con” was discontinued that year, and came and went during that decade. In January 1990, the Canadian on the CP main was discontinued, and the train and the name moved to the CN main. There were shorter-distance trains elsewhere, at the time: between Calgary and Edmonton in Alberta, between Halifax and Sidney in Nova Scotia, and between other points. But at the beginning of 1990, the Conservative government of then-Prime Minister Brian Mulroney cut VIA Rail’s budget so deeply that the system took the vastly reduced form it has today.

More cuts followed. The Atlantic Limited between Montreal and St. John, New Brunswick through northern Maine, came off in 1994, after an earlier disappearance between 1981 and 1985. In 2012, another Conservative government under Prime Minister Stephen Harper did not eliminate any routes completely, but cut frequencies on many of the routes then running. The Malahat, a train on Vancouver Island, came off in 2011. So did the Chaleur, a tri-weekly train between Montreal and Gaspé, on the peninsula of the same name in northeastern Quebec, in 2013. Those two trains were discontinued because of deteriorating track conditions, and there is talk of the latter being restored. Construction is under way on the line between Port Daniel and Gaspé, and there are hopes for restoration in 2026.

Three Business Lines

Both Amtrak and VIA Rail operate corridors and a skeletal network of trains outside those corridors, but the resemblance does not not extend far beyond those similarities. Amtrak has three business lines, which it considers part of its structure: the Northeast Corridor (NEC), state-supported trains and corridors, and the few remaining long-distance trains, a network that has changed little since Amtrak started in 1971. VIA Rail has corridors, too, but nothing with a level of service approaching Amtrak’s NEC, the Keystone trains in Pennsylvania, or Pacific Surfliner service between Los Angeles and San Diego.

According to VIA Rail’s 2022 Annual Report, the railroad refers to “intercity travel” as occurring in its “Corridor” (in the singular, despite several routes). It considers only the Canadian and the Ocean to constitute its “Long-Distance” routes, while all other trains are considered “Regional” and also billed as the railroad’s “Adventure” routes. According to the annual report, there were 3.3 million passengers on VIA Rail in 2022, of which 85% traveled in the Corridor, 13% rode on the two long-distance trans, and the remaining 2% rode on the regional routes. The Corridor accounted for 96% of passenger trips and 81% of revenue, the long-distance trains hosted 3% of trips and 18% of revenue (presumably due to sleeping car fares), and the “regional” accounted for the remaining 1% of passenger trips and revenue.

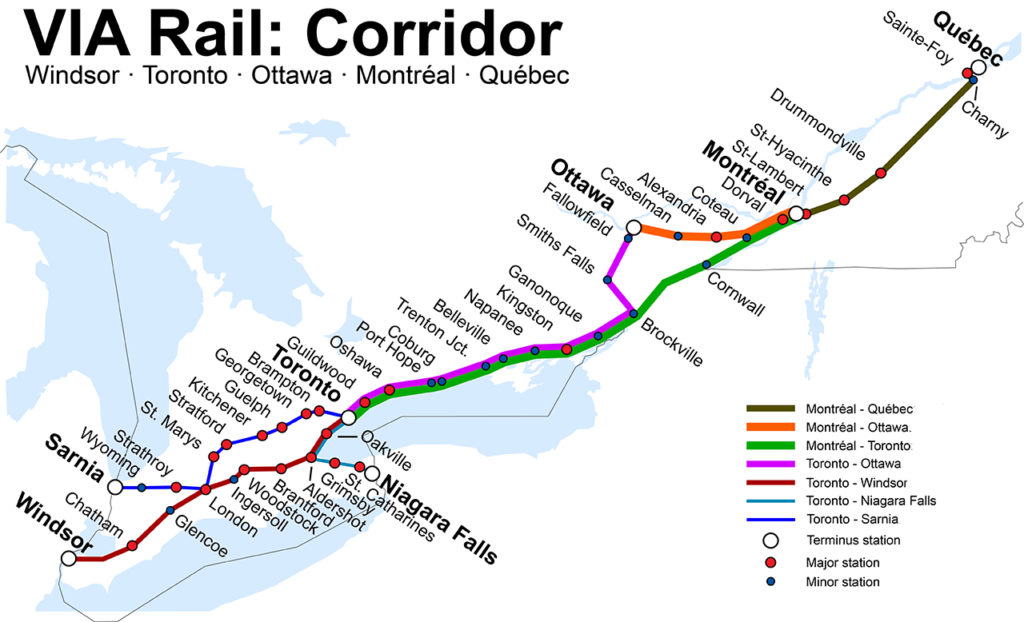

VIA Rail’s Corridor Routes

VIA Rail’s corridors run only in parts of Ontario and Quebec. As can reasonably be expected, the busiest route runs between Ottawa and Toronto, with nine frequencies daily, except eight on Saturdays. There are six frequencies between Montreal and Toronto on weekdays and five on week ends. The other corridors run between Montreal and Quebec City and Montreal and Ottawa, with five trips on weekdays and four on weekends, and Toronto and Windsor, Ontario (across the St. Clair River from Detroit), with four daily round trips. The station is in Walkerville, east of downtown Windsor.

There are only two trains on VIA Rail that run the “once a day” schedules that are still standard on Amtrak’s long-distance routes and a number of state-supported routes in the U.S. One runs between Toronto and Sarnia, Ontario, which is north of Windsor and opposite Port Huron, Mich., itself north of Detroit. That route intersects the Windsor line at London, Ontario, and reaches it by a different route. At one time, there was a through train between Toronto and Chicago, operated by Amtrak on CN in Ontario and CN subsidiary Grand Trunk in Michigan. Today, most of the former route hosts a passenger train, because Amtrak’s Blue Water still runs between Chicago and Port Huron. That train and VIA Rail’s Sarnia train do not connect temporally or physically. One has a schedule to Toronto for the day, and the other has a comparable schedule for Chicago. There is no longer any passenger service through the St. Clair Tunnel between Port Huron and Sarnia.

The other daily single-frequency operation on VIA Rail is the Canadian portion of Amtrak’s Maple Leaf between Niagara Falls and Toronto. Amtrak operates the train on the New York State portion of the route, and VIA Rail operates it on the Ontario side, with its own crews, train numbers, and food for sale in the snack car. The route is served primarily by regional Toronto provider Metrolinx under its GO Transit name on a bus route, along with three daily trains in each direction.

Canada’s Two “Feature Trains”

VIA Rail operates two long-distance trains, one of which has the trappings of rail travel from the past, at least for passengers who are willing or able to spend the money to ride in a sleeping car. That train is the Canadian between Toronto and Vancouver, named for its equipment rather than for its route, and which carries on the traditions of semi-luxurious rail travel that were found on many trains in days gone by. The other is the Ocean train between Montreal and Halifax, where services have been downgraded over the years, and which runs the most unusual consist I have ever encountered. These are the only trains for which VIA Rail has kept the names, at least officially.

The original Canadian was CP’s crack train that ran across much of the nation, from Vancouver to the principal cities of Montreal and Toronto, in two sections that split at Sudbury, Ontario. The trip took three days, and the train’s equipment consisted of one of the last orders of classic streamlined cars, built by the Budd Company for CP in 1954. That equipment still runs today, and the train’s name continues with it, even though it now runs on the CN main, whose comparable train was the Continental Limited, later the Super Continental.

When former Amtrak head Richard Anderson ridiculed Amtrak’s long-distance trains as “experiential” trains, I authored an essay about two genuinely “experiential” trains, headlined “Good ‘Experientials’ or Bad?” from Jan. 23, 2020. One was perhaps America’s best-known tourist railroad, the Durango & Silverton, a sample of mountain-style narrow-gauge railroading on a train pulled by a vintage steam-powered locomotive through the scenic Rockies in Colorado. The other was VIA Rail’s Canadian. What I did not mention in that article was that VIA Rail’s flagship train offers two completely different “experiences” on its four-day (formerly three-day) journey twice a week (formerly three times a week) across Canada. One experience was classic and luxurious by today’s standards, and the other is boring and somewhat grim, the difference being based on how much money the passenger is willing or able to spend. I rode both of those trains recently and will report about them later in this series.

VIA Rail’s “Adventure” Routes

There are five trains on VIA Rail that have no counterpart on Amtrak. They run in remote parts of Canada, and none of them run more often than three times a week. They carry a variety of railfans, adventurous tourists and local folks from remote areas not served by other transportation modes. I rode four of them starting this past August, concluding at Jonquiere, Quebec on Sept. 1.

Four of the five trains are designed to serve remote areas, and the fifth is noted for its Rocky Mountain scenery, becoming a busy “tourist train” during the summer. I rode the first four recently, for the first and probably only time. None of them cross a provincial border, except that the train serving Manitoba ventures into eastern Saskatchewan on its circuitous journey north. They operate in Manitoba, Ontario, and Quebec. The fifth, which I rode almost 25 years ago, operates between Jasper, Alberta and Prince Rupert, B.C., a port town far north of Vancouver and just south of the Alaska Panhandle.

The routes all have their own personalities (although the two in Quebec are very similar), and VIA Rail used to honor them with names. The railroad removed the names several years ago by official fiat, but folks who remember the names still use them. It appears to constitute a disservice to those trains that they “lost their names” officially, and I will use them in this series, for ease of identification, if for no other reason. In every case, it appeared that local residents viewed the trains as a sort of lifeline to the outside world, whether for riding or for shipping relatively small items in the train’s baggage car.

The best-known is the train between Winnipeg and Churchill, Manitoba, historically known as the Hudson Bay. More than the other trains on the railroad, it draws adventure-seekers who travel for the experience, which includes time in Churchill, a town on Hudson Bay (also called “Hudson’s Bay”), 16 hours from the nearest highway. Railfans travel to northern Ontario to ride the historically named Lake Superior between Sudbury and White River. It is the only VIA Rail train operating in CP (now part of CPKC) territory, except for a few short segments of the Canadian. It is also the last scheduled train in North America that operates with Rail Diesel Cars (RDCs) built by the Budd Company in the 1950s, also known as “Budd cars.” Locals call it the “Budd train” and, for many riders, it evoked memories of an innovative type of car from days gone by. The two trains in Quebec are similar: the historic Abitibi to Senneterre in northwestern Quebec, and the historic Sagunay to Jonquiere, north of Quebec City. The two trains run combined from Montreal until they split at Hervey Junction, about four hours north. I will report on my experiences on those trains later in this series.

The Train Not Taken

The only non-corridor train on VIA Rail that I did not ride recently was the historic Skeena in British Columbia, with a small amount of mileage in western Alberta. It runs three times a week between Prince Rupert, B.C. and Jasper, Alberta, where the Canadian also stops, but the two trains do not make convenient connections. It was named for the Skeena River, along which it makes some of its two-day journey. The train has not changed much since I rode it in 1999, but the experience I had then is no longer available. At that time, I rode from North Vancouver to Prince George on the British Columbia Railway, on a train that consisted of two Budd cars. After an overnight layover, I took the Skeena to Prince Rupert, spent the night there, and then rode the train all the way to Jasper, Alberta, with the same overnight layover at Prince George. The train was scheduled to misconnect with the eastbound Canadian at Jasper in those days, too, so I took a bus on Greyhound Canada to Edmonton where I spent two days before going east on my way home. Greyhound Canada no longer exists, either.

During the summer season, the train carries a number of “tourist class” cars, coaches that are equipped to serve meals to passengers at their seats. At the time I rode, I was told that many of the riders on that extra-fare service came from Japan and other east-Asian countries, and wanted to see the Canadian Rockies up close. Of course, there were (and presumably still are) Canadians and Americans who want the same experience.

When I rode, it was the middle of May, the week before “tourist class” season began. Behind a single locomotive, the consist included only one coach and a round-end observation car from the Budd-built 1954-vintage Canadian fleet (called a “Park Car” at VIA Rail). There were only about 25 or 30 of us on board for the trip. Most of us congregated in the dome section of the Park Car, and the trip felt like a party on a chartered train.

Today’s schedule is similar to the one that ran back then. It is a two-day trip, leaving Jasper early in the afternoon and arriving at Prince George for an overnight layover. Riders are on their own to secure accommodations. The train left the next morning for an all-day trip to Prince Rupert scheduled to take more than twelve hours. The return trip to Jasper is scheduled to arrive late in the afternoon.

Eating along the route was problematic, since the train carried only an observation car with limited snack service available. The Jasper segment was short enough to allow an opportunity to eat there before departure westbound or after arrival eastbound. The twelve-hour Prince Rupert segment did not allow a comparable opportunity. During the brief standing time at Smithers, B.C. for a fuel stop, I found a luncheonette within a block of the station and ordered soup and a sandwich to eat on the train. Because I took that chance, I ate better than any of the other passengers.

Overall, the Skeena was a pleasant experience, but it is so inconvenient with the number of nights and days of layover time that it is not a journey suitable for the uninitiated.

Observations

In my recent travels, I did not go anywhere west of Manitoba, except for the portion of the Hudson Bay train to Churchill, which ventures into eastern Saskatchewan for about six hours. Except for the Skeena, though, I rode every non-corridor train that VIA Rail operates today. For the most part, I enjoyed the experiences, and the interactions with the crew members and other passengers were positive. There were some exceptions, too, and I will report on each of the trains I rode later in this series.

The classic Budd equipment brought back wonderful memories. Both the RDC cars on the Lake Superior “Budd train” and the streamlined equipment on the other trains rode well and reminded me of another era that ended about 30 years ago, when Amtrak took almost all the pre-Amtrak equipment out of service. For comfort and ride quality, that equipment remains unsurpassed in the U.S. or Canada.

The people on the train were interesting, and the crews were helpful, with one exception. Everybody on the train wanted to be there, from the “locals” who needed the trains to go anywhere, to the railfans, to the tourists who were looking for an interesting experience, to the folks who live in cities like Winnipeg or Montreal and had to go to places along the routes. Everybody, including the crew members, had stories, and many were interesting. These are travel experience not available in the U.S. anymore (except perhaps on the Alaska Railroad, which is on my “bucket list” for next year).

There was one problem that I encountered on every train: the lack of good, available food. My strongest suggestion for anyone planning to ride anywhere on VIA Rail, except for a corridor-length trip, is to stock up on food and bring it on board. Pretend that you are going on a trip to the “frontier” and that you must pack whatever you eat, because, in fact, you are. You can purchase a cup of coffee (for C$3.00), but not much more. Even on VIA Rail’s flagship trains, the Canadian and the Ocean, food options for coach passengers are extremely limited, and there are not many places to buy food.

Of the 26 days I spent in Canada, I spent twelve of them mostly or entirely on VIA Rail, along with portions of another three. That does not count the time getting to or from some of these trains on the few buses that still run in Canada. As I previously reported, I spent several other days riding rail transit.

Except for the lack of good food on VIA Rail, I enjoyed the trip and will always remember the experiences I had along the way. I have now ridden all of VIA Rail, along with all of Amtrak, and I wonder how many other people (if anybody) has also completed riding both systems. Clearly, if one person can ride on all routes of “America’s Railroad” and Canada’s railroad, there are not enough passenger trains in either country. While that particular issue is beyond the purview of this series, there will be many travel experiences, both on and off the train, to report.

I will report on VIA Rail’s feature train, the Canadian, in the next article in this series.

David Peter Alan is one of America’s most experienced transit users and advocates, having ridden every rail transit line in the U.S., and most Canadian systems. He has also ridden the entire Amtrak and VIA Rail network. His advocacy on the national scene focuses on the Rail Users’ Network (RUN), where he has been a Board member since 2005. Locally in New Jersey, he served as Chair of the Lackawanna Coalition for 21 years, and remains a member. He is also Chair of NJ Transit’s Senior Citizens and Disabled Residents Transportation Advisory Committee (SCDRTAC). When not writing or traveling, he practices law in the fields of Intellectual Property (Patents, Trademarks and Copyright) and business law. Opinions expressed here are his own.