More Choices For ‘Dashing Commuters’

Written by David Peter Alan, Contributing Editor

New Kawasaki M9 EMU at Penn Station New York. (Wikimedia Commons/Bebo2good1)

RAILWAY AGE, OCTOBER 2023 ISSUE: In its 190th year, the Long Island Rail Road settles into new routines—and so do its riders.

During the late 1960s, famed folksinger Oscar Brand (who hosted a program for New York’s WNYC for more than 70 years) was hired to perform a number of advertising jingles for the Long Island Rail Road (LIRR) in radio commercials. He sang of “boxy trains for boxes” and of “shoppers’ trains for ladies, commuter trains for dads” and lots of other varieties of trains on the railroad, including “party trains for teens.” Prior to this, the LIRR in the 1950s created a nickname that stuck: “The Route of the Dashing Commuter,” with its mascots, “Dashing Dan” and “Dashing Dottie.”

Times had changed greatly from the time the railroad began until Brand (who lived along the LIRR’s line to Port Washington) sang the railroad’s praises. They have also changed greatly since then for the oldest railroad in the U.S. still operating under its original name and charter.

Still Going At 189!

The Long Island Rail-Road Company began operations in 1834. Nobody thought about “commuting” that far back; the word had not yet been coined. Instead, the railroad’s purpose was to help provide a one-day trip between New York and Boston. Its main line had reached Greenport by 1844, which established the Boston route. Passengers would take a ferry from Manhattan to the LIRR dock at Williamsburgh, Brooklyn (which soon dropped the “h” from its name), ride to Greenport, take another ferry to Stonington, Conn. (east of New London), and another train to Boston. The trip took about 11 hours. Today, it’s possible to make a similar trip, which takes about 8 to 9½ hours, depending on the day of the week, several hours more than a direct ride on Amtrak’s Northeast Corridor.

To provide as fast a trip as possible, the LIRR was built through the middle of Long Island and not through populated areas. Its business dropped off significantly when the Shore Line in Connecticut on the New York, New Haven & Hartford Railroad (predecessor of the NEC) opened in 1848, providing an all-rail route to New York. The LIRR faced financial difficulties at that time but kept going by concentrating on serving Long Island itself. During the rest of the 19th century, it added several other lines, including the one to Montauk, and was able to buy other railroad companies on Long Island, including the New York & Flushing Railroad and the Central Railroad of Long Island.

The LIRR held a local railroad monopoly when the Pennsylvania Railroad (PRR) acquired it in 1900. The PRR began to electrify some LIRR trackage in 1905, and the 1910 completion of Pennsylvania Station in New York City eliminated the need to take a ferry across the East River. This allowed the railroad to develop its commuter services to places on the island, the mainstay of its operations ever since.

During the PRR period, the LIRR not only expanded its commuter network, but also ran trains to resort areas at the east end of the island: trains like the Cannonball (still running today as a seasonal weekend train) and the Sunrise Special to Montauk, and the Fisherman’s Special running an overnight schedule similar to one that still runs today, only without the name. There was also the Shelter Island Express to Greenport on the North Fork. The railroad still serves those routes, with an emphasis on summer service to the Hamptons and Montauk, but no longer with the parlor cars that ran back then.

By 1946, the PRR faced its own financial difficulties, and the State of New York began to subsidize the LIRR in the 1950s. That led to the State’s purchase of the railroad in 1965 and its transfer to the Metropolitan Commuter Transportation Authority, which became the MTA that we know today in 1968. Since that time, the MTA expanded electrification, converted the entire railroad to high-level platforms, and modernized equipment, starting with the M-1 cars in 1970 and continuing through today’s M-9 models, as well as dual-mode locomotives and bi-level cars on its four non-electrified lines.

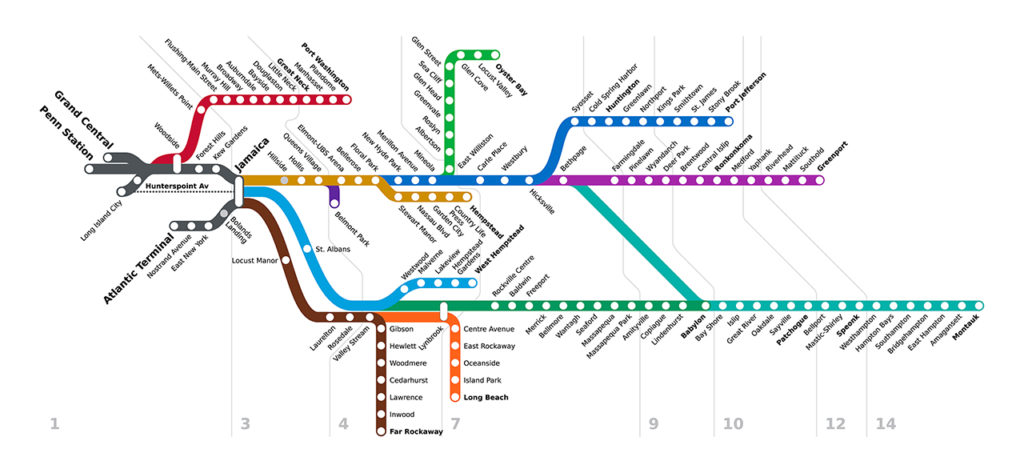

LIRR System Map

Where LIRR Goes

The LIRR today consists of four lines within New York City converging at Jamaica, and nine branches east of there. The two major Manhattan terminals are Penn Station and the new deep-cavern Grand Central Madison (GCM), originally called East Side Access. The original tracks from Penn Station and the newly-constructed ones from GCM join just after reaching ground level in Queens, and head to Jamaica. So does the Atlantic Branch from Atlantic Terminal in Brooklyn, which contains the first tracks built by the LIRR in the 1830s. A few trains run to or from Hunterspoint Avenue in Queens during peak commuting hours. The line between Penn Station and Port Washington branches off at Woodside, Queens, west of Jamaica.

Headed east, the LIRR’s northern portion starts with the Main Line to Ronkonkoma and Greenport, also known as the Ronkonkoma Branch. It is only electrified as far as Ronkonkoma. Branching off from it are the Port Jefferson Branch (electrified as far as Huntington), the Oyster Bay Branch (not electrified), and the Hempstead Branch (electrified, branching off in Queens). The spine on the south side of the island goes to Montauk, near the end of the island’s south fork. The electrification and most of the trains only run as far as Babylon. Three electrified branches split off from it at or near Valley Stream in western Nassau County, to Long Beach, Far Rockaway and West Hempstead. There is also the Central Branch, which runs between Bethpage on the Main Line and Babylon. Only a few trains heading east of Babylon use it, and it has no station stops, but there are plans to electrify it.

Another major project that is part of the MTA’s 2020-24 capital plan is the LIRR Main Line Expansion, which completed a third track on ten miles of the Main Line, from Floral Park in eastern Queens to Hicksville on Oct. 3, 2022. The MTA says that line is used by 40% of LIRR customers.

GCM, The Game Changer

For the first time since Penn Station opened in 1910, there is now a new LIRR terminal in Manhattan. It is Grand Central Madison, the culmination of the multi-year, multi-billion-dollar East Side Access project. GCM is located deep under Madison Avenue, slightly west of historic Grand Central Terminal, built in 1913 by the New York Central. (GCT hosts Metro-North, the MTA’s other commuter railroad.) Construction started in 2008, and the new terminal opened for business on Jan. 25, 2023 with limited service. The first month of service included only shuttle trains between the new station and Jamaica. Full service began on Feb. 27.

GCM has eight tracks on two levels, with two island platforms on each level. Tracks are numbered 201-204 and 301-304, as a continuation of the two-digit numbers for tracks on the main concourse at GCT and the 100-series numbers of the lower-level tracks at that station. Only single-level electric multiple-unit trains use the new terminal because the tunnel from there to Queens does not have enough clearance for bi-levels.

GCM’s concourse runs in a cavern under Madison Avenue, 140 feet below street level. The platforms are located further down. According to the MTA, from the GCM concourse to the mezzanine level between the 200 and 300 platform levels is 91 feet down. From those platforms, it took me eight minutes to walk to the historic headhouse at GCT, and ten minutes to get to 42nd Street. Riders going to buildings along Madison Avenue within a few blocks north of GCT can get to their destinations faster.

To some extent, it is obvious that the new terminal has added a degree of flexibility for Manhattan commuters and other riders. In the most basic terms, the LIRR now serves both the East and West sides of Manhattan, where it previously served only the West Side. That observation begs the question of how much convenience the new terminal has added, and for how many riders. The time required to get from a platform to street level (and vice-versa) reduces the advantage for some riders, compared to continuing to use Penn Station.

How Much Mobility Gain?

It could be questioned to what extent the LIRR has established schedules that allow riders to go to or from the two Manhattan terminals more often than was the case in the past, even though there are more trains today. Service patterns from either Manhattan station seem similar to the ones in effect before GCM opened, so the additional trains might not translate to that much additional access.

The Babylon Branch, one of the busiest lines, features service to and from both Manhattan terminals, but there is hourly service to and from GCM, and separately to and from Penn Station, with a few more trains to Penn. Most trains on the Far Rockaway, Long Beach and Hempstead Branches serve GCM, while only a few serve Penn Station, similar to the former pattern when most ran to or from Brooklyn. The non-electrified or partially electrified lines carry times for both Penn Station and GCM with Note J, which means “Transfer at Jamaica,” similar to pre-GCM schedules that carried comparable information for Penn Station and Brooklyn.

On the Port Washington Branch, there is service about every 30 minutes at Woodside and points east, alternating between Penn Station and GCM. The Ronkonkoma Branch schedule has the same arrangement, but it does not indicate that a rider can “Transfer at Jamaica” for a train that came from the “other” point of origin. The limited Greenport service uses shuttle trains to and from Ronkonkoma.

There are also four schedules for the “City Terminal Zone”: for Penn Station, GCM, Atlantic Terminal in Brooklyn, and Forest Hills and Kew Gardens, intermediate stops between Penn Station and Jamaica. While it might be feasible to check those schedules to determine whether a train from Penn Station can connect at Jamaica with a train from Grand Central Madison to a desired destination or vice versa, that maneuver is not easy or convenient, and is definitely not suitable for the “uninitiated” occasional rider. Despite some objections to the new changes, there are now 115 morning-peak inbound trains through Jamaica between 5:38 and 9:29 AM and another 113 outbound trains between 4:29 and 8:16 PM. Nearly all of them originate or terminate at either Penn Station or GCM.

What Happened To Brooklyn?

Atlantic Terminal in Brooklyn seems to have almost disappeared from the timetables on the LIRR section of the MTA website. The only line that features the Atlantic Terminal is West Hempstead, where weekend and off-peak weekday service originates and terminates. On other lines, eight weekday through trains are scheduled to arrive in Brooklyn in the morning, and five are scheduled to leave in the late afternoon and early evening. The rest of the service consists of shuttle trains to and from Jamaica that use a new platform, separate from the platforms where trains used to line up for transfers. They are scheduled about every 12 minutes during commuting periods, every 20 minutes on weekends, and roughly every 30 minutes at other times on weekdays, although a few gaps are longer.

MTA spokesperson Dave Steckel said that less that 7% of LIRR riders go to Atlantic Terminal and praised the frequency of the current shuttle service, adding that the railroad will continue to monitor ridership and make changes. Since GCM opened for full service, a few trains have been added to the Brooklyn schedule, and some others have been shifted from GCM to Penn Station.

Transfer at Jamaica?

Before GCM opened, trains had timed meets at Jamaica. The very phrase “Change at Jamaica” became a local expression among New Yorkers. The premise was that a train from Penn Station and a train from Brooklyn would meet at Jamaica for a cross-platform transfer. After exchanging passengers, the trains would go their separate ways. There were also three-way meets, where a train that originated at Hunterspoint Avenue or at Jamaica would be stationed on another nearby track, and the three trains would exchange passengers for all ultimate destinations. Former LIRR planner Joe Clift recalled, “Amazing to me was that you could transfer between two trains through a ‘bridge train’ in the middle.”

Steckel told Railway Age that the LIRR could not continue the traditional practice of timed transfers at Jamaica because there are now so many trains running that it is not feasible to hold trains for timed connections under current schedules. He suggested that customers use the TrainTime app to plan their trips. He also expressed concern that, if it became necessary for trains to wait at Jamaica for a late connection, it could cause cascading delays and possibly lead to service reductions in the future.

At the present time, the LIRR—the nation’s busiest commuter operation—touts major service improvements. Steckel said that there is 41% more service now than before GCM opened, and there are now improved “reverse commute” opportunities. Those certainly help, but time will tell just how much those changes improve mobility to, from, and on Long Island. It will also tell whether GCM was worth the cost in the long run.