STB Dismisses BNSF, NTEC Case (UPDATED Dec. 14)

Written by Marybeth Luczak, Executive Editor

BNSF and Navajo Transitional Energy Company, LLC (NTEC) last month told the Surface Transportation Board (STB) that they had reached a settlement agreement to resolve their common carrier dispute. The STB on Dec. 13 dismissed the proceedings in light of the settlement and lifted the previously imposed preliminary injunction.

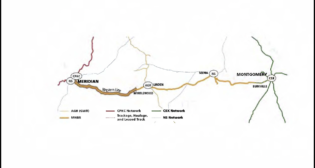

The case stems from NTEC’s April 14, 2023 application to the STB seeking an emergency service order pursuant to 49 U.S.C. § 11123. In addition, or alternatively, it sought a preliminary injunction under 49 U.S.C. § 1321(b)(4). NTEC asked the STB to direct BNSF “to restore and maintain adequate coal transportation service” from its Spring Creek Mine in Big Horn County, Mont., to the Westshore Terminals facility in British Columbia, Canada. In a separate docket, NTEC filed a related complaint and petition for declaratory order alleging that BNSF breached its common carrier obligation, failed to provide adequate car service, and engaged in unreasonable practices with respect to the transportation at issue.

The STB in its Dec. 13 decision (download below) said that “[a]ll pending claims in Docket Nos. NOR 42178 and NOR 42179 are dismissed with prejudice and the dockets are closed,” and “[t]he preliminary injunction issued on June 23, 2023, in Docket No. NOR 42178 [which required the Class I to this year transport millions of tons of coal from the NTEC mine in Big Horn County to the export facility in British Columbia] is lifted.” Board Members Patrick J. Fuchs and Michelle A. Schultz dissented with separate expressions from the portion of the majority’s decision that denies NTEC’s motion to vacate the June 2023 Decision.

“In the agency’s case law and public declarations, the Board has generally recognized that the parties themselves are best positioned to identify mutually beneficial solutions to complex disputes, and the Board has therefore encouraged parties to settle their differences privately,” Fuchs wrote in his separate expression (read as part of STB Decision, above). “The parties here … have reached settlement in both dockets. In notifying the Board of the settlement, NTEC submitted an unopposed request to vacate the Board’s June 23, 2023, preliminary injunction decision designed for NTEC’s own benefit. In today’s decision (Decision), the Board rejects this request. As a result, the Decision in effect raises future bargaining costs for moving parties, who might need to give up more to compensate for the Board’s unpredictability in considering mutually agreeable solutions. The Board might accept this negative effect so it can preserve what it sees as valuable precedent, but—for several reasons explained in my prior dissents on this matter—the precedent should be eliminated, not preserved. Accordingly, though I concur with the Decision’s dismissal of all claims with prejudice and closure of both dockets, I respectfully dissent from the Decision’s refusal to vacate the Injunction Decision.”

Fuchs wrote that “[g]iven the precedent in this case and considering potential similar cases in the future,” his expression focused “on the implications of the Board’s finding related to the common carrier obligation, and emphasized that “the Board ought to value flexibility, resiliency, and service-related outcomes and effects so that it avoids harming broad groups of shippers, penalizing crucial rail capacity, and imposing unnecessary costs on the network.”

According to Fuchs, the STB going forward “could best avoid many unintended consequences by assembling all the facts in a dispute, focusing on outcomes and effects, and, if warranted, awarding damages.” He noted that “oftentimes in this network industry, when one shipper experiences a service problem, other shippers are similarly experiencing service problems. Indeed, in this proceeding, three other shippers opposed the emergency relief and preliminary injunction that NTEC sought. Given the relatively fixed nature of capacity in the near term, it is extraordinarily difficult to design an effective injunction or emergency service order that completely avoids negative effects on other shippers. Thus, for good reason, the Board has traditionally cabined urgent and immediate intervention to emergency situations, such as imminent threats to public health, where it can accept negative effects on other shippers in furtherance of a greater countervailing public benefit. The Board has wisely declined to treat economic harms, including reputational damage, as irreparable harm, avoiding more difficult immediate trade-offs between shippers with similar economic profiles when the Board can award damages later. As a general matter, if the Board must intervene prior to hearing all the facts and deciding the underlying complaint, it ought to steer clear of directly regulating resource levels, or their availability, particularly when it does not have information to effectively judge or enforce, and it should instead focus on outcomes and effects. When the Board takes the extraordinary step of issuing an injunction or emergency service order, it should consider limiting its order to short time periods. In similar future cases, the Board must exercise caution and restraint—not just to run a fair process for carriers—but to protect other shippers and the broader public.”

Schultz’s expression was similar. “I respectfully dissent from the portion of majority’s decision (Decision) that denies NTEC’s unopposed motion to vacate the Board’s June 23, 2023 decision … that granted NTEC preliminary injunctive relief,” she wrote. “Because the parties have reached a settlement agreement that resolves all the claims in these proceedings, I find no basis for denying the motion, nor does the Decision offer any explanation for doing so. The agency’s general policy has been to grant requests to vacate prior decisions when parties have agreed to settle the issues underlying the proceeding … This agency has, on occasion, made exceptions where the prior decisions set forth new legal principles or interpretations that provide valuable guidance to future litigants … The Decision provides no reason why that exception should apply here. In support, the Decision cites two cases where courts have regarded the “social value” of precedent as the basis for denying motions to vacate prior decisions. But the Decision fails to explain what, if any, precedential value the June 2023 Decision holds, as that decision itself acknowledges, the Board’s findings were largely based on facts relevant only in the context of that proceeding.”

She wrote that “[t]o the extent that future litigants might rely on the June 2023 Decision for guidance in determining a carrier’s common carrier obligation, the precedential value of that decision is questionable. The findings in the June 2023 Decision are based on the ‘reasonableness’ of NTEC’s request, and that reasonableness was assessed according to a carrier’s purported ‘capacity,’ while never defining ‘capacity’ or explaining how to measure it. As a result, I do not believe the June 2023 Decision provides useful guidance in defining or assessing a carrier’s common carrier obligation under 49 U.S.C. § 11101; nor did it adequately explain how BNSF violated its common carrier obligation. I do not see, nor does the Decision explain, how the June 2023 Decision offers useful guidance to future litigants.”

Noted an industry observer on Nov. 13, prior to the STB decision: “BNSF looking to avoid STB decision making as it smartly saw what was coming were the STB to decide the case on merits. Recall that while BNSF lost on injunction, that injunction mostly required them to do what they said they planned to do. Even Patrick Fuchs, in his dissent, specifically wrote he was reserving judgment on the merits of the case until more evidence was available. The STB sought additional briefing (presentation of evidence) on potential damages in the Union Pacific/Sanimax case. (Sanimax’s brief is due in December; UP’s in January.) That case has been lingering at the Board for three years.”

BACKGROUND

“[M]isconceived and intrusive” is what BNSF recently called the STB’s June 2023 preliminary injunction requiring the Class I to this year transport millions of tons of coal from Navajo Transitional Energy Company, LLC’s (NTEC) mine in Big Horn County, Mont., to an export facility in British Columbia, Canada. The Class I on July 28 filed a lawsuit against the federal agency in U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit. On Aug. 14, STB denied BNSF’s petition for partial stay of the Board’s previous decision in Navajo Transitional Energy Company, LLC – Ex Parte Petition for Emergency Service Order, Docket No. NOR 42178.

STB, in a three-to-two vote, denied BNSF’s petition for partial stay “because BNSF has failed to show that irreparable harm will occur if a stay is not granted,” STB said. “The relief ordered by the Board—that BNSF must transport additional tonnage if capacity to do so becomes available—negates the possibility of irreparable harm to BNSF. The additional tonnage portion of the Board’s order only comes into force through voluntary actions by BNSF to develop additional capacity.” Board members Patrick Fuchs and Michelle Schultz dissented with separate expressions.

The Board’s Aug. 14 decision may be viewed and downloaded below:

BNSF wrote in its lawsuit that the STB had ordered it “to provide common-carrier service to NTEC in 2023 to transport (a) 4.2 million tons of coal from Montana to Canada for export and (b) if resources ‘are available,’ … an additional 1 million tons (the ‘contingent portion’ of the injunction)” (download below).

“That total volume would be unprecedented for NTEC, and yet, because this is common-carrier service, NTEC has no obligation to ship anything at all,” the railroad continued. (The railroads’ common carrier obligation requires carriers to provide service upon “reasonable request.”) “BNSF is now enjoined to stand ready to move billions of pounds of coal, never mind the effects on its network and the diversion of resources away from serving other shippers.

“In theory, without resource constraints, NTEC could request whatever it wanted, and BNSF would easily carry NTEC’s shipments. But in the real world, shippers must make reasonable requests, railroads must respond reasonably in light of their limited resources and the competing demands of other shippers, and regulators must judge the reasonableness of the request and the response.”

BNSF said that the Board’s decision is “divorced from those realities, and it must be vacated.” Additionally, “[o]f most immediate concern, the injunction’s contingent portion must be stayed.” BNSF said that STB “committed one legal error after another.” According to the railroad, STB “failed to properly assess the reasonableness of NTEC’s request. Then it asked merely whether BNSF had the theoretical ‘capacity’ to carry NTEC’s coal, rather than evaluating the reasonableness of BNSF’s decisions in light of BNSF’s resources and competing demands. Then it elevated to irreparable-harm status the garden-variety commercial issues that any shipper and railroad face in a service dispute—expenses incurred or profits lost when shipments are delayed. And then it failed to account for the public’s interest in having railroads run by railroads, not by a federal agency handing out regulatory advantages that don’t exist in the free market.”

BNSF said it was requesting “the minimum relief necessary at this stage.” According to the railroad, “[i]t appears that BNSF can meet the 4.2-million-ton mark in 2023 without overly compromising its operations or other shippers’ interests.” However, it said, “[w]hatever BNSF’s precise obligations are to ensure that resources ‘are available,’ … (the [STB] injunction does not say), shipping an additional 1 million tons would require taking equipment and crews away from other shippers, or investing in resources that NTEC would have no obligation to use.” BNSF said that a “stay of that latter part of the injunction would avoid putting BNSF to those costly choices (for which it cannot be made whole after the injunction is vacated). And that partial stay will not irreparably harm NTEC, when that 1 million tons represents a small portion (just over 1%) of its annual coal production.”

The Class I explained that although its motion “is not an emergency matter under Circuit Rule 27.3, BNSF has serious need for the Court to resolve this motion by late August.” While BNSF “has been providing service to NTEC at a pace that is likely to comply with the Board’s 4.2-million-ton requirement, which BNSF does not ask this Court to stay,” the railroad said “[a]s the end of the year draws closer, it becomes increasingly difficult or impossible to increase the volume of shipments by 1 million tons to comply with the contingent portion of the injunction. A combination of seasonal cycles that peak in the fourth quarter in the Pacific Northwest—including increased shipments of domestic coal as winter approaches, increased intermodal container traffic, and agricultural traffic from the fall harvest—make it especially difficult to significantly expand service for any shipper. Thus, BNSF needs 1-2 months’ lead time to plan traffic on its network and communicate those plans to other shippers whose shipments may be constrained if BNSF is required to serve NTEC at the Board-ordered level. BNSF therefore respectfully requests a decision on this motion by August 31, 2023.”

BNSF concluded that the court “should stay the contingent portion of the Board’s injunction pending full review.” The railroad concurrently filed a motion to expedite the proceedings (download below).

In announcing its June 23 decision, the STB said it found that “NTEC prevailed on the four-part test for granting injunctive relief.” Specifically, the STB reported finding “that NTEC was highly likely to succeed on the merits of its claim that BNSF violated its statutory common carrier obligation to transport the volume of coal tendered by NTEC. On this prong, the Board found that NTEC’s request for service was reasonable, in light of BNSF’s historical performance, and factual statements in BNSF’S pleadings and at oral argument that BNSF has the capacity to provide the minimum service requested by NTEC.” STB said it also found that “NTEC was likely to suffer irreparable harm, such as significant damage to its reputation as a dependable supplier in the global coal marketplace, which cannot be remedied by money damages. The Board found that balancing the needs of other BNSF customers did not weigh against an injunction because the record establishes that BNSF can comply with the injunction and still meet the needs of other shippers. Finally, the Board found that an injunction serves the public interest because NTEC has shown that it plays a critical role in the Navajo Nation’s economy. The Board further acknowledged that there is a public interest in accessing the rail network.”

“The common carrier obligation is a core tenet of the Board’s regulation of the freight railroad industry and is a pillar of the railroads’ responsibility to our country’s economy,” STB Chairman Martin J. Oberman said during the announcement. “Today’s decision reflects the majority’s finding that the common carrier obligation requires a railroad to provide service on a customer’s request that is within the railroad’s capacity to provide.”

Oberman added, as the STB said it has previously held: “The common carrier duty reflects the well-established principle that railroads ‘are held to a higher standard of responsibility than most private enterprises.’”

Board members Patrick Fuchs and Michelle Schultz dissented with separate expressions.

‘Stay Pending Review’

BNSF in its court filing reported that “[f]or a stay pending review, this court ‘consider[s] four factors: (1) whether the requester makes a strong showing that it [is] likely to succeed on the merits; (2) whether the requester will be irreparably injured without a stay; (3) whether other interested parties will be irreparably injured by a stay; and (4) where the public interest lies.”

The railroad argued that:

- “BNSF is likely to succeed on the merits, especially with respect to the contingent portion.” According to the railroad, STB “applies a traditional four-factor preliminary injunction analysis, considering (1) the movant’s likelihood of success, (2) irreparable harm to the movant absent an injunction, (3) harm to other interested parties if an injunction were entered, and (4) the public interest … The Board’s error on a single factor would be sufficient to vacate its decision, but the Board erred each step of the way—arbitrarily ignoring facts, disregarding its own precedent without explanation, acting contrary to judicial precedent, and failing to rationally connect the facts it found to the injunction it issued.” BNSF reported that the “Board’s analysis of whether NTEC made a ‘reasonable request’ for shipment ignored the real-world facts. NTEC requested that BNSF transport more than 5.2 million tons of coal from Spring Creek to Westshore during 2023. … That request exceeded the maximum amount ever shipped from Spring Creek to Westshore in a single year (in 2021).” Additionally, BNSF said the “Board missed an entire step in the common-carrier analysis. Even if NTEC’s request had been ‘reasonable,’ BNSF’s common-carrier obligation is not a mandate to provide all the service a shipper demands; BNSF’s obligation is to provide ‘adequate’ service under the circumstances.” BNSF also said the STB “committed legal error in finding that NTEC would suffer irreparable harm absent an injunction,” and that its “analysis of the harms to other interested parties and the public interest is also unlikely to withstand judicial review.”

- “BNSF faces irreparable harm absent a stay.” BNSF said the “affirmative obligations under the contingent portion of the injunction are unclear, but anything they demand puts BNSF at risk of taking actions that will incur unrecoverable costs or liabilities if the injunction is overturned.” For example, it said, “acquiring and repositioning train sets would take time and resources from BNSF, but the injunction imposes no obligations on NTEC—not to utilize those train sets, not to pay liquidated damages for failing to meet a minimum-volume commitment, or indeed to do anything. BNSF has no way of recouping its expenditures if NTEC does not use BNSF’s service.” According to the railroad, “[i]f the contingent portion of the preliminary injunction requires BNSF to cut service to other shippers, BNSF may have to breach its contracts, or face other shippers’ common-carrier complaints—trapping BNSF in a Catch-22 of the Board’s own making. Here, too, compliance with the injunction will come at a cost to BNSF, but BNSF will have no path to being made whole if this Court overturns it. The Board majority accounted for none of this.”

- “A stay will not irreparably harm NTEC.” According to BNSF, “NTEC, the real party in interest here, would face no harm if a stay were granted—and indeed, it did not argue before the Board that it would be harmed by a partial stay … NTEC faces no irreparable harm—especially not from a stay of the contingent portion, which concerns a volume equal to scarcely more than 1% of NTEC’s total annual coal sales. The very fact that the additional 1 million tons is contingent suggests it is not at all necessary to avoid irreparable harm.”

- “The public interest supports a stay.” According to BNSF, the STB’s “injunction ‘undermines commercial collaboration between rail carriers and shippers,’ App173 (Fuchs, dissenting), and it warps the incentives to negotiate contracts, App174 (Fuchs, dissenting), both of which harm the public. The adverse effect of the preliminary injunction on the public interest supports a stay.”

Commentary: Frank Wilner

“BNSF is questioning the STB’s exercise of authority under an ill-defined by Congress common carrier obligation,” Railway Age Capitol Hill Contributing Editor Frank N. Wilner tells Railway Age. “Fleshing out the common carrier obligation is a foremost objective of STB Chairman Martin J. Oberman. Significantly, the STB’s successful defense before the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals, which is hearing the case, will rest with the court’s granting so-called Chevron deference, named for an underlying 1984 Supreme Court decision instructing lower courts to defer to expert Executive Branch and independent regulatory agencies the task of filling in statutory gaps lacking direct language on specific points. Chevron deference, however, may be limited or terminated by the Supreme Court next year as the Court’s conservative majority appears wedded to a credence that it is the province and duty of courts, not regulatory agencies, to determine what the law intends.” [Editor’s note: Wilner explores this issue further in his August “Watching Washington” column and, more so, in his new book, Railroads & Economic Regulation. Wilner has been Assistant Vice President, Policy at the Association of American Railroads; a White House appointed chief of staff at the Surface Transportation Board; and director of public relations for the United Transportation Union.]

NTEC Status Report

NTEC on Aug. 4 released to the STB the following status report on BNSF service:

“Pursuant to the Board’s June 23, 2023 Decision and Order (‘Decision’), Navajo Transitional Energy Company, LLC (‘NTEC’) hereby submits the following report:

- “BNSF originated twenty-three (23) Spring Creek export trains for NTEC during the month of July. BNSF has originated two (2) Spring Creek export trains for NTEC so far during the month of August.

- “Given the BNSF service levels currently available to NTEC, it remains the case that additional trainsets do not appear to be needed. Accordingly, while NTEC will continue to monitor the market for additional trainsets, it has not pursued any commitments for additional trainsets given these service levels.”

![“This record growth [in fiscal year 2024’s third quarter] is a direct result of our innovative logistic solutions during supply chain disruptions as shippers focus on diversifying their trade lanes,” Port NOLA President and CEO and New Orleans Public Belt (NOPB) CEO Brandy D. Christian said during a May 2 announcement (Port NOLA Photograph)](https://www.railwayage.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/portnola-315x168.png)