Book Review: Railroads & Economic Regulation, An Insider’s Account

Written by Jim Blaze, Contributing Editor

Railroads & Economic Regulation, An Insider’s Account. By Frank N. Wilner. Simmons-Boardman Books. Hardcover, 398 pp. $69.00

Frank N. Wilner, a Railway Age colleague and Capitol Hill Contributing Editor, has researched and extensively footnoted the economic growth and then the shrinkage of our nation’s railroad system. Here, Wilner focuses on the people that were involved in overseeing that giant railway network as “regulators.” It is a timeline documentary. The introduction is written by former STB Chief Economist William F. Huneke and contains essays by shipper attorneys Michael F. McBride and Robert D. Rosenberg and rail lobbyist Ray B. Chambers.

This long-time rail economist/engineer found that, through my lens, Wilner’s book actually offers those now in charge a checklist of problems vs. opportunities to possibly reshape and re-energize this bricks-and-mortar transportation mode into an improved freight service industry for our public use as receivers and shippers.

Reflecting and integrating with what I have learned during five decades, here’s the company I place Wilner in now after absorbing his admittedly somewhat “dry” regulatory work: He is, with this work, “our” mentor.

It’s hard to manage the options of improving any enterprise or organization if you can’t understand what the problems and past choices have done to create this business competition morass. Wilner gives us that perspective in the book.

I’ve been blessed by other mentors in my long rail career. There have been lessons learned from many mentors, from Jim Hagen to Jim McClellan and John Williams. From Stanley Crane to David LeVan. And from rail sector engineers like Lou Thompson and Dr Allan M. Zarembski. From supply chain leaders like Dr. Kant Rao and Marvan Manheim, and from fellow economists/financial reviewers like Chris Rooney and Steve Ditmeyer. From marketing experts like Prof. Bill Black and Kel Kavanaugh. A diverse, skilled group, with (sadly) quite a few left off my list in order to be brief.

Now I add Frank Wilner to this list of teachers. His documented evidence about the regulatory side of the railroad business is welcomed and appreciated.

To those looking daily to improve as managers and overseers, this book is a well-documented series of citations, giving the younger generation coming up behind us now a commercial/political perspective of how history often gets shaped behind the curtain of building fronts. It’s an insider’s view of smoke-filled rooms, in some instances. As former FRA Administrator Allan Rutter (2001-2004) notes, “This is a great read for anyone wanting to learn not only about railroad history but about how our government has functioned since the Progressive Era.”

The narrative identifies how we got to our nation’s current railroad commercial status. There is overwhelming detail in the book—so much detail that perhaps a searchable PDF file version of Wilner’s labor would be a functional reference to the generation that is now going to oversee regulatory decisions. Particularly important is that most of us recognize that the railroad sector has been losing its relative market share position.

Wilner’s account lays out the minefield yet to be cleared. In part, he has written an essential combat mission manual, but one that is intellectual and interpretative reading. That’s what I conclude is the value he delivers. It’s not surprsing that three-time Pulitzer Prize winning investigative journalist Walt Bogdanich of The New York Times wrote of Wilner in 2009, “When researching the railroad industry, any investigative journalist that doesn’t start with a phone call to Frank Wilner is making a big mistake. He shoots straight and he knows the industry inside and out.” In a 1996 Supreme Court decision, Justice Clarence Thomas cited Wilner’s writing three times.

In part, Wilner offers us a review of the historical geopolitics used for regulatory oversight, about various roles at different times played by some powerful people, and the characteristics of the institutional relationship networks as “the regulators came and went” as appointed persons.

The Interstate Commerce Commission (now Surface Transportation Board) appointment process since 1887 has often displayed a more protective umbrella-like role for the delegated persons rather than an openness by her or him toward rail service improvement or commercial experimentation. Relatively few leaders over the past 136 years have offered ideas that might “freshen up” the performance of the industry they were appointed to regulate. Yes, there are always some exceptions, and Wilner singles out many, some by way of footnotes.

Wilner couldn’t document too many instances where the appointment method to the ICC/STB brought forward modern-day logistics management (supply chain) educated staff or voting commissioners. Yes, again there are exceptions.

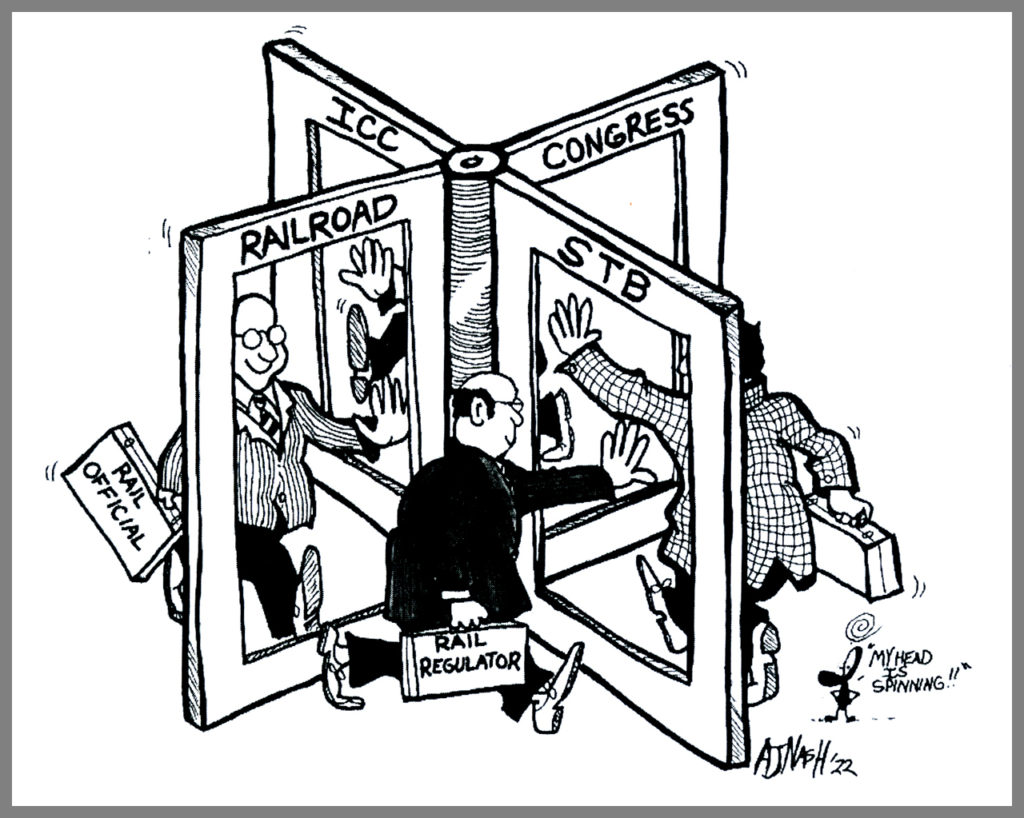

But the most stunning historical reminder to this old railroad guy was the cartoon image of the revolving door on page 362 (Appendix G)—something over my long rail career I had not considered as “roadblock” behavior. I was a bit naive. In 2023, is this still the appointment pattern? Maybe less so.

This image marks a different definition of “serve and protect.” It seems like a type of isolation, in contrast to worldwide supply chain organizations that are openly reengineering their business models. Somewhat disturbing is today’s less and less relevant rail freight market share vs. trucking. Sadly, today’s STB is increasingly discussing the fate of a shrinking-market-share industry. Do they understand that? This relative shrinking has got to be frustrating to all the participants.

Wilner selectively documents experimentation with ratemaking, cost allocation budgeting and discriminatory pricing across the 136-year history of U.S. railroad regulation. The standout characteristic? To this economist, it appears as if it’s taking place within an academy, where highly argumentative debates occur within a very legalistic decision-making group. It feels like a very time-consuming procedural process—no rapid changes, as the markets they watch over shift at a much more rapid pace. Not experimental. Not part of STB DNA. There really hasn’t been active deliberation within as to how to competitively respond to the now dominant highway truck business competition, but there has at least been an awareness.

There were some extraordinary changes afoot during the 1960s and 1970s, such as the 3-R Act and 4-R Act that created Conrail from the ashes of the Penn Central and six other bankrupt Northeastern carriers. The Rock Island and Milwaukee Road financial situations did result in creative change. But these changes largely bypassed an ICC role. The regulatory rate and other business process changes allowed by the 1980 Staggers Rail Act came principally from outsiders like Rep. James Florio from New Jersey, who led the effort—resisted, as I interpret Wilner’s detailed references, by some more used to the revolving-door ICC environment. He does document some of the exceptions, providing, therefore, important historical fact checking.

Let me quickly share a few tidbits hidden in the 398 pages.

Wilner describes how some appointed leaders rose to prominent positions and offered new insights. Here are a few of my favorite “fun facts.” How many of these do you know about?

In 1944, a Board of Investigation and Research estimated that the total of federal land grants to railroad companies only amounted to about 130 million acres. The ability of those early railroads allowed them to sell off small tracts to help finance new track construction. But the total income from those land grants helped fund fewer than maybe 19,000 miles of the eventual 254,000-mile national network at its zenith. That’s a mere ~7% of the eventual high point of rail track coverage by the year 1916. Statistician and economist Bill Behling was the author of that report.

To receive that federal aid, the land-grant railroads (like Union Pacific) were required to carry U.S. government cargo at a 50% discount to the then-prevailing rail rates until 1945, through World War I and World War II. What a great commercial deal for the taxpayer that was, I conclude.

Overbuilding resulted in way too much carrying capacity. In 1900, reports circulated that “the then-existing railway lines were capable of transporting twice or thrice the tonnage” than being offered by shippers. Rates started to drop as carriers struggled to obtain a critical mass of the traffic for their lines. The financial strength of the railroad companies faltered. Bankruptcies eventually took place—and abandonments followed.

President Grover Cleveland signed the legislation creating the ICC on Feb. 4, 1887. While not in favor of regulation as an investor, even William H. Vanderbilt of the mighty New York Central had to agree to support the ICC regulatory legislation.

The future of rail passenger service might have early on been projected by none other than Amelia Earhart. Wilner cites her from a 1930 address to a group of railroad attorneys. She said, “I don’t see why the railroads don’t just hand over their [long-distance] passengers [to the airlines].”

As Wilner reminds us, 41 years later, Steve Goodman wrote these haunting lyrics:

“Fifteen cars and fifteen restless riders. Three conductors and 25 sacks of mail. This train got the disappearing railroad blues. Good night, America, how are you? Don’t you know me? I’m your native son. I’m the train they call the City of New Orleans. I’ll be gone 500 miles when the day is done.”

Perhaps my favorite citation offered by Wilner is this statement by Fortune Magazine’s Mina Kimes. In 2011, she asked if the U.S. freight railroads were more of a cartel or a free-market success story. A rebirth, like a longing in the Dark Ages for a return to the magic times of Rome and ancient Greece? A different way of wishing for a Renaissance, or a modernization as something new? Frank Wilner captures that historical perspective about the regulated railroad sector. It’s best said with this one quote from his book:

“In most industries, rising profits are cause for celebration. In the railroad business, they are a touchstone for controversy.”

Still the case in 2023?

Independent railway economist and Railway Age Contributing Editor Jim Blaze has been in the railroad industry for close to 50 years. Trained in logistics, he served seven years with the Illinois DOT as a Chicago long-range freight planner and almost two years with the USRA technical staff in Washington, D.C. Jim then spent 21 years with Conrail in cross-functional strategic roles from branch line economics to mergers, IT, logistics, and corporate change. He followed this with 20 years of international consulting at rail engineering firm Zeta-Tech Associated. Jim is a Magna Cum Laude Graduate of St Anselm’s College with a master’s degree from the University of Chicago. Married with six children, he lives outside of Philadelphia. “This column reflects my continued passion for the future of railroading as a competitive industry,” says Jim. “Only by occasionally challenging our institutions can we probe for better quality and performance. My opinions are my own, independent of Railway Age. As always, contrary business opinions are welcome.”