Transitions can be difficult

Written by Lawrence H Kaufman, Contributing EditorThe death recently of A. E. (Ted) Michon reminded me just how difficult transitions can be for those who must go through them.

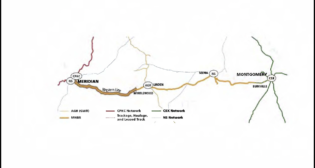

Ted, a former Burlington Northern Railroad vice president, was one of the “good guys.” He was one of the executives who took BN into the coal business, opening up and developing the huge Powder River Basin coal fields in Wyoming and Montana, and in the process guaranteed BN’s survival as the U.S. railroad industry consolidated to its current seven Class 1 carriers.. He later was regional vice president of the BN in Portland, Ore.

After establishing himself as a strategic planner, Ted moved on to BN rival Union Pacific and eventually was a leader of the small team of U.S. railroad executives who helped privatize the Polish railroads after the collapse of the Soviet Union.

Ted’s BN career peaked about the time that the Staggers Rail Act of 1980 was passed and the U.S. railroad industry was substantially deregulated. He was eased out of BN well before he was ready to retire. In that, he was like many railroad executives of his era. The men—and they were almost invariably men—of that generation were forced to go through wrenching change that they neither anticipated nor ever thought they would be forced to endure. Deregulation not only changed the way they did their jobs, it changed what their jobs were.

Those at the very top of the various railroads had no real problems. They controlled the industry and were in positions where they could protect themselves. Similarly, the people at the bottom of the managerial pyramid were net ahead of all the changes. The industry’s renaissance triggered by deregulation soon resulted in their having better tools, more resources, and new focus by those who gave them their marching orders. They ended up with better jobs.

It was the mid-level executives who were forced to do the greatest amount of changing. Their world was turned upside down by deregulation. They went from running trains to a newfound demand that customers be satisfied by the price they demanded and the quality of service provided.

Before deregulation, all rail business was conducted according to provisions of tariffs. Railroads could not guarantee their service and many executives found it easy to ignore complaining shippers, telling them to complain to the Interstate Commerce Commission, which regulated virtually every aspect of the railroad business. Deregulation, for the first time, allowed railroads to negotiate both price and service agreements.

Ted Michon was one who made the transition better than others. Many of Ted’s contemporaries stumbled through the changes until they could retire. Some, who had been considered strong candidates to become senior executives or even president or chief executive of major railroads before Staggers discovered they had had their last promotion.

Some simply were not able to adapt and left the railroad industry. Those who wanted to retain seniority became consultants advising railroads how to adapt to the newfound freedom that had been thrust on them. Some who were closer to retirement chose to exercise seniority they had jealously guarded over the years, dropping back into positions where they were represented and protected by union collective bargaining agreements.

Some executives demonstrated that they had the talent and drive needed to succeed in the new railroad industry all along. They include chief executives of today’s prosperous railroads. Others, initially surprised by the tectonic shift that resulted from deregulation, were good enough executives to see and make the changes that were required.

The change in management approach was not so much driven by good or bad executives as it was a reflection of the truth that it takes different skills to manage an enterprise that must scramble to survive than to manage one that is growing.

Cost-cutting, the time-honored way of surviving, rarely results in prosperity. Nor does it encourage or reward risk-taking. On the other hand, where the enterprise is successful, executives who understand how to manage growth will prosper in ways their predecessors could not. Planning capital investment programs and managing for the future is more satisfying than pinching pennies.

![“This record growth [in fiscal year 2024’s third quarter] is a direct result of our innovative logistic solutions during supply chain disruptions as shippers focus on diversifying their trade lanes,” Port NOLA President and CEO and New Orleans Public Belt (NOPB) CEO Brandy D. Christian said during a May 2 announcement (Port NOLA Photograph)](https://www.railwayage.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/portnola-315x168.png)