Chemical companies keep up doubletalk

Written by Lawrence H Kaufman, Contributing EditorStaggers is the law that effectively deregulated much of the railroad industry. It is considered to be highly successful and a major factor in reinvigorating the U.S. railroad industry. Not everyone thinks so highly of Staggers, though.

Bulk shippers of coal, chemicals, and some grains never wanted to see their rail service suppliers deregulated. They knew they had a good thing going. Besides, under regulation, railroads were barely able to stay in business. Any change in regulation undoubtedly would result in improved railroad finances.

And that’s exactly what happened. It didn’t happen overnight, but once the railroads began to generate respectable and improving earnings, they managed to keep the process going.

Now the ACC recently bought a “study” from a consulting firm that works exclusively for rail shippers. It should come as no surprise to learn that the study concludes that if railroads charged no more than the 180% of variable cost that is the threshold for the continuing regulation that still exists, chemical shippers would earn billions more and create thousands of new jobs.

And I, of course, am the long lost son of the last Czar of Russia. Some people will believe anything, especially if it is neatly packaged.

The chemical producers and their consultants would prefer that 180% of variable cost be a “cap” on rail rates, not a threshold. Under Staggers, any rate that is below the 180 trigger is considered evidence that competition exists and government intervention in the rate-setting process is not needed. Above 180, a complaining shipper still must establish that its rail carrier has market dominance. If it can, then, and only then, it may pursue a complaint that the railroad is charging unreasonable rates. If it prevails, the Surface Transportation Board—the regulator—can order a refund with interest and may prescribe a rate, but not below the 180 threshold.

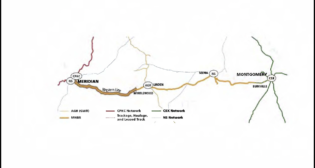

This month (February) marks the third anniversary of Berkshire Hathaway Inc.’s $44 billion purchase of BNSF Railway. BH’s chief executive Warren Buffett, known as the “Oracle of Omaha,” said at the time that the transaction was his “all-in” bet on the future of the U.S. economy. With BNSF reporting record earnings and spending record amounts of capital to maintain and upgrade its property, owning a railroad looks like a good deal.

Instead of buying studies from less-than-impartial consultants, perhaps some chemical companies might consider doing what Buffett did—buy their very own railroad. I guarantee you that idea will go nowhere.

Despite the fact that some of the chemical companies are bigger than any of the major railroads, and some are bigger than the entire railroad industry, they will reject the idea out of hand on the ground that no railroad has a return on investment (ROI) that meets their investment criteria.

Oh, they’ll offer up some other reasons for not buying a railroad. They will point out that they ship multiple products from multiple origins to multiple destinations. As though that should make a difference.

Businesses exist for one purpose: to earn a profit. Today, we have chemical producers complaining that rail rates have increased over recent years. So which is it? Do railroads make “too much” at the expense of giant chemical companies? Or are railroads not sufficiently profitable to justify a chemical company owning one? Both cannot be true at the same time.

![“This record growth [in fiscal year 2024’s third quarter] is a direct result of our innovative logistic solutions during supply chain disruptions as shippers focus on diversifying their trade lanes,” Port NOLA President and CEO and New Orleans Public Belt (NOPB) CEO Brandy D. Christian said during a May 2 announcement (Port NOLA Photograph)](https://www.railwayage.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/portnola-315x168.png)