Medical fitness-for-duty standards: Where are they?

Written by William C. Keppen, Jr.

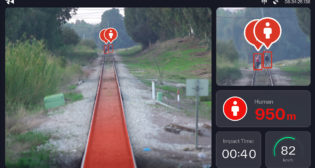

BNSF photo from NTSB’s accident report.

“According to the BNSF employment records for the 52-year old male striking train engineer, a pre-employment physical examination and health questionnaire dated June 28, 1994, identified no significant medical conditions.” Hold that thought.

On June 28, 2016, at 8:21 AM CDT on the barren plains of West Texas, two BNSF freight trains collided, head-on, at a combined speed of approximately 100 mph. The incident claimed the lives of three train crew members and caused tens of millions of dollars in damage to equipment and collateral cost. Three years later, the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) finally released a Railroad Accident Brief on this tragic incident. Make no mistake, this and several other similar incidents were not “accidents.” They were the predictable result of the railroad industry’s failure to monitor the medical fitness-for-duty of train operating personnel. As a result, some people are operating trains, putting themselves and others at risk, when they are not medically fit for duty.

How is it that the NTSB had to go way back to 1994—22 years—in company medical records to obtain information on the medical fitness of the locomotive engineer who was operating the train that caused this collision? That would mean the railroad had no real idea of the medical status of this engineer, or many others for that matter. How is it that both crew members of the striking train had medical conditions, and were taking medications, that would have disqualified a commercial vehicle operator from driving a truck, yet they were allowed to operate trains? How can that happen in an industry that thunders through towns and cities all across America carrying all kinds of goods, including hazardous materials, at speeds of up to 70 mph?

Here is how that can happen. For more than 100 years, railroads self-regulated employee medical standards and fitness-for-duty decisions. However, very quietly after the enactment of HIPAA and ADA, many railroads ceased their requirements for periodic and comprehensive physical examinations for their train operating crews. In their place, railroads established programs to ensure locomotive engineers and conductors met vision and hearing standards, as required by Federal Railroad Administration (FRA) regulations. In addition, railroads issued rules requiring these and several other employee groups to report medical conditions that could adversely affect their alertness and/or job performance.

We could point the proverbial finger at the railroads for having ineffective medical oversight protocols or at employees for failing to do as directed and report medical conditions that could affect their job performance, but that would overlook the root cause of these disasters: The FRA’s failure to establish comprehensive medical fitness-for-duty standards and protocols for train operating personnel.

In early 2005, a study (DOT/FRA/RRS-05/01) dated January 2005, commissioned by FRA and titled “Medical Standards for Railroad Workers” was presented to railroad industry stakeholders at a meeting in Washington, D.C. I know because I was there. I still have my copy. The first sentence of the Executive Summary of that report states, “Failure to recognize potentially incapacitating medical conditions can have serious safety consequences for railroad employees, the railroads and the public.” How prophetic.

Section 9.1 Conclusions, on page 129 of the study report, listed ten conclusions, among them:

- There is a need for a consistent industry-wide medical standards program for railroad workers performing safety-sensitive functions.

- This need will increase due to the aging work force.

- The FRA medial program is significantly less comprehensive than that of other DOT modal administrations and other countries.

- There have been several accidents and injuries due to the medical condition of the employee. A medical standards program could likely have prevented these accidents.

Section 9.2 Recommendations states, in part, “The FRA should proceed to develop a medical standards program for the railroad industry in accordance with the following recommendations:

- The need for a medical program exists, and this need will increase due to the aging work for. Therefore the FRA should expedite the development process to the extent possible.” (Four others follow.)

What then? FRA punted the ball to the Railroad Safety Advisory Committee (RSAC), where it languished for years. Lacking consensus, the committee, which is made up primarily of railroad management and railroad labor, could not make recommendations to FRA on how to proceed, at which point FRA could have, and should have, proceeded with a medical standards rulemaking. But it didn’t. Even after these issues were raised again, in the 2008 Rail Safety Improvement Act (RSIA), FRA failed to initiate the processes necessary to enact medical standards regulations.

Ask yourself these questions:

1) Is this an industry that is responsible enough to self-regulate?

2) Is the FRA fulfilling what should be its primary mission, protecting public and rail workplace safety?

3) Who should be held accountable, and how?

4) When will the public and railroad workers themselves be afforded the protection of fair and effective medical fitness-for-duty standards and protocols?

I believe I can provide plausible answers to the first two, no and no, but I’ll be damned if I can answer numbers three and four.

William C. Keppen Jr., a retired BLET (Brotherhood of Locomotive Engineers and Trainmen) Vice President and third-generation locomotive engineer at BNSF and predecessors Chicago, Burlington & Quincy and Burlington Northern, is an independent transportation advocate with experience in fatigue countermeasures programs. A railroad industry veteran of almost 50 years, Keppen provides safety analyses for Confidential Close Call Reporting System (C3RS) programs in freight, commuter, and light rail transportation. Keppen was Project Coordinator for BNSF’s Fatigue Countermeasures Program, and former BLE General Chairman for the BN Northlines GCA. “I started working on human-factor-caused train accidents in 1980,” he says. “It has been a struggle. I would like to think I have made a difference, but there are still far to many human-factor-caused train ‘accidents,’ which I prefer to refer to as ‘preventable incidents.’”

William C. Keppen Jr., a retired BLET (Brotherhood of Locomotive Engineers and Trainmen) Vice President and third-generation locomotive engineer at BNSF and predecessors Chicago, Burlington & Quincy and Burlington Northern, is an independent transportation advocate with experience in fatigue countermeasures programs. A railroad industry veteran of almost 50 years, Keppen provides safety analyses for Confidential Close Call Reporting System (C3RS) programs in freight, commuter, and light rail transportation. Keppen was Project Coordinator for BNSF’s Fatigue Countermeasures Program, and former BLE General Chairman for the BN Northlines GCA. “I started working on human-factor-caused train accidents in 1980,” he says. “It has been a struggle. I would like to think I have made a difference, but there are still far to many human-factor-caused train ‘accidents,’ which I prefer to refer to as ‘preventable incidents.’”