CP Disputing TSB Accident Report

Written by Marybeth Luczak, Executive Editor

Mid-train distributed power remote locomotive, UP 5359, following the 2019 derailment of CP’s freight train 301-349 on the Laggan Subdivision, near Field, British Columbia. Source: TSB Report R19C0015.

Canada’s Transportation Safety Board (TSB) at a March 31 news conference released its investigation report of Canadian Pacific’s Feb. 4, 2019 train derailment on the Laggan Subdivision near Field, British Columbia. CP later in the day issued a strong statement, calling out “inaccuracies and misrepresentations” made at the conference and in the report.

The TSB report (R19C0015) identified a number of “safety deficiencies” contributing to the accident that killed three crewmembers:

“• The degradation of air brake systems in extreme cold temperatures.

“• The limitations of current train brake test methodologies to accurately evaluate air brake performance in these temperatures.

“• Training that was not specific to the unique operating conditions of the Laggan Subdivision, and the inadequacy of experience of employees supervising mountain-grade [defined by CP as grades exceeding 1.8%] operations on this subdivision.

“• The need for better identification of hazards through reporting, data trend analysis, and risk assessments under CP’s safety management system to support risk mitigation measures.

“• The need for additional physical defenses to prevent uncontrolled movement of rolling stock.”

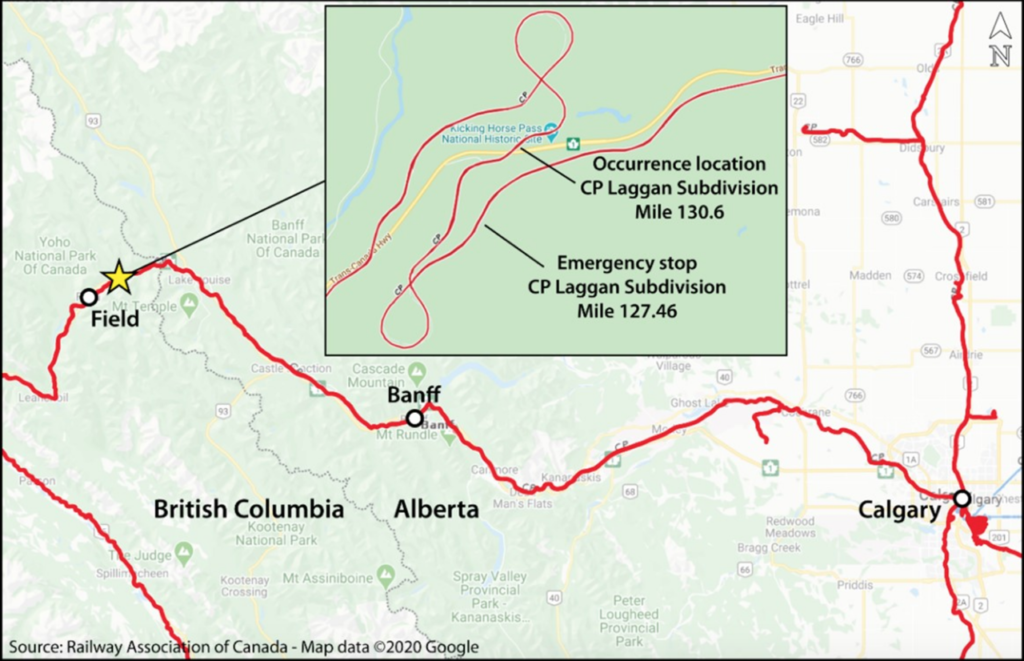

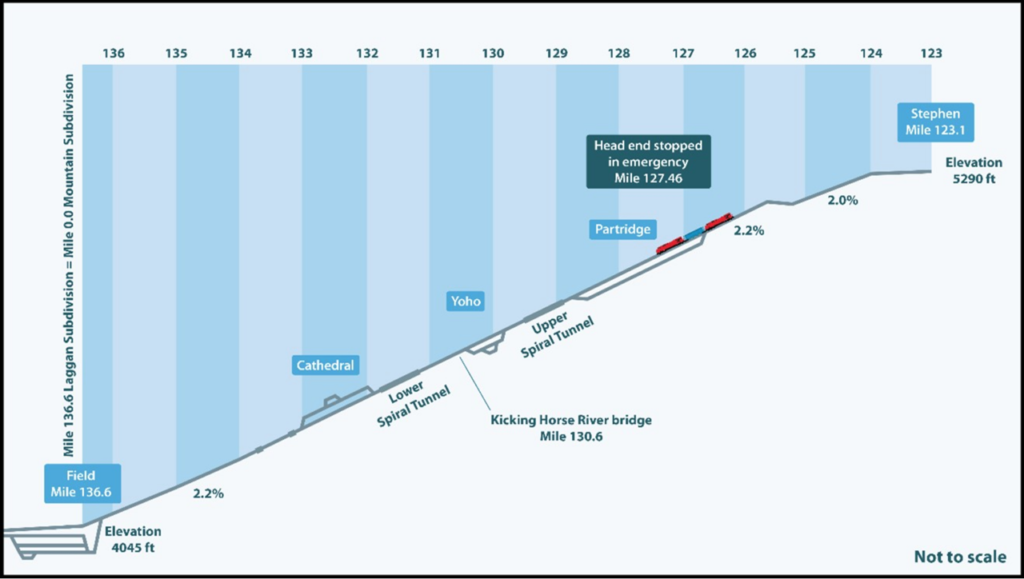

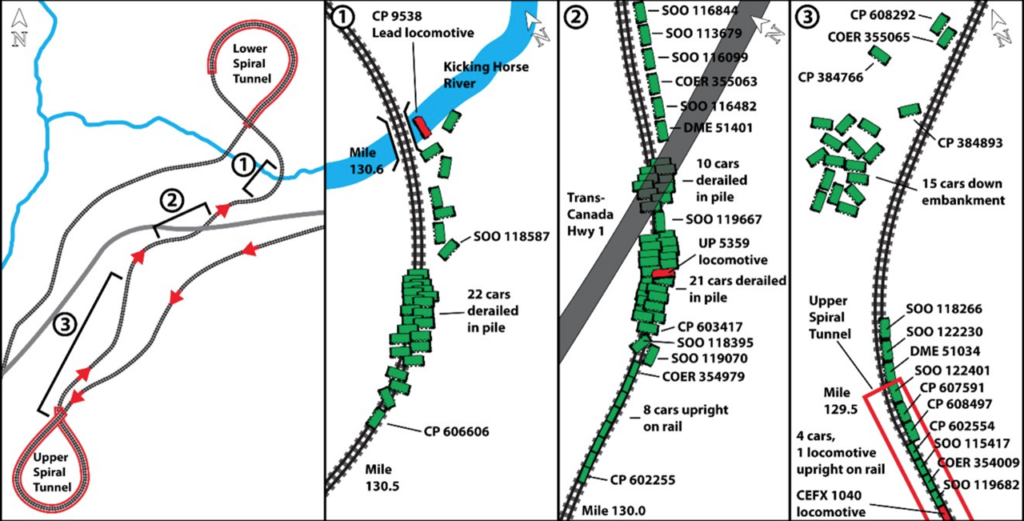

What led to the derailment? According to TSB, on Feb. 3, 2019 “a CP unit grain train with 112 loaded hopper cars was traveling from Calgary, AB to Vancouver, BC. While descending the steep 13.5-mile-long Field Hill [with a grade averaging 2.2%], the inbound train crew was not able to maintain the required speed and applied the brakes in emergency, bringing the train to a stop at 9:49 pm [MT]. The brake cylinder pressure retaining valves were set on 84 cars to retain residual air pressure, which would facilitate getting the train under way again, allowing the air brakes to recharge as it continued its descent. A relief crew was called in to replace the inbound crew as they were at the end of their shift. During this time, the train’s air brake system had been leaking brake cylinder pressure, reducing the capacity to keep the train stopped on the grade. Shortly after the relief crew took over, at 12:42 am [MT] on 4 February, the train began to creep forward and accelerate uncontrolled down the steep grade. The train reached 53 mph, and was unable to negotiate a sharp curve, resulting in the derailment of two locomotives and 99 cars, and the three relief crewmembers being fatally injured.”

The TSB’s investigation found that the “brake cylinders on the freight cars were leaking compressed air, a situation made worse by their age and condition, and exposure to extreme cold temperatures over time. It was determined that after being stationary on the hill for around three hours, air leakage reached a critical threshold and the brakes could no longer hold the train on the steep grade.

“The inbound locomotive engineer had observed indications of brake system anomalies. Although these were discussed with the trainmaster, they were not recognized as problematic. Additionally, because the situation was the first emergency stop, critical factors were not considered, and only the pressure retaining valves were applied, rather than the retaining valves and hand brakes. In this instance, the trainmaster’s training and experience did not adequately prepare him to evaluate the circumstances or to make the decision he was tasked with.”

As the investigation was unfolding, TSB reported that it “issued three Rail Safety Advisories to communicate safety critical information to Transport Canada.” The advisories “urged Transport Canada to address the following deficiencies:

“• the adequacy of braking performance of grain cars in CP’s fleet,

“• residual risk for trains stopped in emergency on grades less than 1.8%,

“• the need for an alternate approach to determine the effectiveness of freight car air brakes.”

After the accident, Transport Canada introduced several initiatives, “including a Ministerial Order requiring that trains stopped by an emergency brake application on a grade of 1.8% or greater immediately apply a sufficient number of hand brakes before recharging the air brake system,” according to TSB. “The Ministerial Order was later repealed when it was superseded by Rule 66 of the Canadian Rail Operating Rules.” Transport Canada also “approved the use of automated train brake effectiveness technology in lieu of No. 1 brake tests on CP’s unit grain trains operating between points in Western Canada and the Port of Vancouver.”

TSB reported that, for its part, CP:

“• revised the train handling procedures for the Laggan Subdivision with respect to the use of retainers and hand brakes before recovering from an emergency brake application on mountain grades;

“• issued Operating Bulletin OPER-AB-015-19, which introduced both new cold-weather speed restrictions for Field Hill for trains with a weight per operative brake of 100 tons or greater and a requirement that undesired releases of brakes on Field Hill be reported immediately to the rail traffic controller;

“• monitored wheel temperatures on all westbound grain trains passing by detectors installed on the Laggan and the Mountain subdivisions, which resulted in more than 5,000 grain cars being removed from service for repair;

“• developed an advanced training program for locomotive engineers to build their skills and readiness for dealing with adverse conditions in the field. Adverse conditions covered by the training program included response to minor and major changes in air flow and brake pipe fluctuation, response to an undesired release of the air brakes, and procedures for emergency air brake recovery.”

TSB Recommendations

In an aim “to enhance safety of cold-weather train operations through mountainous territory,” TSB is now making these three recommendations to Transport Canada:

1. Establish “enhanced test standards and requirements for time-based maintenance of brake cylinders on freight cars operating on steep descending grades in cold ambient temperatures. (TSB Recommendation R22-01)”

2. Require “Canadian freight railways to develop and implement a schedule for the installation of automatic parking brakes on freight cars, prioritizing the retrofit of cars used in bulk commodity unit trains in mountain grade territory. (TSB Recommendation R22-02)”

3. Require CP “to demonstrate that its safety management system can effectively identify hazards arising from operations using all available information, including employee hazard reports and data trends; assess the associated risks; and implement mitigation measures and validate that they are effective. (TSB Recommendation R22-03)”

“This tragic accident demonstrates, once again, that uncontrolled movements of rolling stock continue to pose a significant safety risk to railway operations in Canada,” TSB Chair Kathy Fox said. “It is obvious that more must be done to reduce the risks to railway employees and the Canadian public, reduce preventable loss of life, and increase the safety and resilience of this vital part of the Canadian supply chain.”

CP Responds

CP on March 31 issued the following statement regarding TSB’s investigation report:

“CP continues to mourn the loss of [conductor] Dylan Paradis, [engineer] Andrew Dockrell and [trainee] Daniel Waldenberger-Bulmer. This is a tragedy that will never be forgotten and one which has strengthened CP’s unwavering commitment to safety across its entire operation.

“Given the gravity of this incident and the tragic loss of life, it was extremely disappointing that the TSB misrepresented the facts at today’s news conference and misunderstood key facts about the incident in its report. Specifically:

“• At the news conference, the TSB’s Manager, Head Office and Western Regional Operations-Rail, misrepresented what happened on the locomotive when the relief crew arrived to relieve the inbound crew. The relief crew did not immediately decide to apply handbrakes upon arriving at the locomotive. The report itself contradicts his statement. Per the TSB report, the relief crew had been on board the locomotive for over 20 minutes and had performed another job briefing before the train started to move. No decision to apply handbrakes was made during this time.

“• The assessment of the situation and the decision to apply brake retainers were made using the collective knowledge and experience of everyone involved. Both the locomotive engineers of the inbound crew and the relief crew were fully-trained, qualified and certified, and were well-experienced in the handling of trains on mountain grades. The trainmaster was also a qualified locomotive engineer with experience on mountain grades. Both crews and trainmaster agreed on the appropriate steps to be taken in line with existing procedure. The Field Hill operating procedure itself was based on operating practices established in collaboration with the running trades employees, Transport Canada and company management in the wake of previous incidents more than two decades ago. This was not an issue of training and/or experience.

“• The TSB has erroneously concluded, based on inappropriate extrapolation of data and unsupported inferences, that the involved-train exhibited poor braking performance. As confirmed in the report, the train involved in the incident was fully functional, met all industry standards and passed all regulatory brake test inspections.

“• CP demonstrated that its Safety Management System contains all of the necessary elements as required by regulations. CP’s safety hazard reporting procedure was effective, both in form and in execution. There were no systemic hazards that were not appropriately addressed, including Field Hill train braking performance, by CP’s Safety Management System.

“• CP has a robust training and certification program that meets or exceeds applicable regulatory standards, utilizing leading technology and focusing on practical application. Learning at CP is never complete, and CP’s training programs are continuously being updated and refined using the most current practices and learnings to confirm complete understanding.

“CP has a strong culture of safety and always works to improve. CP remains the industry leader in technology-driven train inspections with a decade-long track record of reduced train accidents and improved train performance.

“Throughout this investigation, CP fully cooperated with the TSB. CP strongly believes that real and substantive safety improvements are only achieved when fact-based and objective analysis is undertaken to truly understand the causes and contributing factors of an incident like the Field derailment.

“CP will be addressing the inaccuracies and misrepresentations made at today’s news conference and in the report in greater detail directly with the TSB.

“This matter remains the subject of a preliminary inquiry by the RCMP [Royal Canadian Mounted Police].”