NJT Hoboken 2016, the Final 39 Seconds

Written by David Schanoes, Contributing EditorThe news of the day the other day read “Train Engineer in Fatal 2016 Hoboken Train Crash Wins Back Job with NJT.” The locomotive engineer, Thomas Gallagher, had been dismissed after over-running the end of Track 5 in Hoboken Terminal. The resulting collision damaged the supports for the train shed roof. A woman not on the train but walking on a platform was killed as she was struck by the collapsing structure.

Later, Gallagher was diagnosed with obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). The arbitration panel, established under Section 3 of the Railway Labor Act, heard his appeal against the dismissal, and determined that NJT’s medical professionals had not followed NJ’’s own protocol for determining if an employee was at risk for OSA. Gallagher was reinstated with full seniority, but restricted in his duties to other than passenger train operation.

I’m certainly not here to argue against the Railway Labor Act, special boards of adjustment, this decision or the restoration of Gallagher’s seniority. Those are, in the scheme of things, minor issues, minor disputes that have little bearing on the overall safety of train operations.

A major issue, painfully illuminated by this sad case, is the necessity for a comprehensive, system-wide regulation that establishes protocols for the diagnosis and treatment of OSA among railroad employees assigned to the movement of trains, or the maintenance of track, signals and rolling stock. The Federal Railroad Administration needs to adopt or adapt, or both, the protocols already established by other federal agencies and do it outside the process of the Rail Safety Advisory Committee (RSAC) mechanism.

RSAC fashions and recommends regulation by consensus. For the past 13 years, there has been no consensus between carriers and labor organizations on the issue of testing and treatment for OSA, and there isn’t going to be consensus in the next 13 years either. But there are going to be more accidents where a crew member is later diagnosed with OSA, after others pay the price of waiting for consensus.

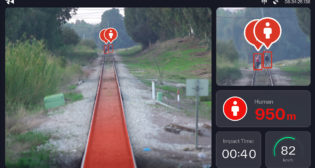

That’s one. As for two: What does Hoboken mean for “low speed” terminal operations? Was OSA the root cause of the accident and the level of destruction? I think we can answer that by reviewing information in the NTSB’s accident docket. If we examine the event recorder data from the control car, we find that approximately 39 seconds prior to the impact with the bumping block at the end of the track, the train’s velocity was 8 mph. For reasons unknown, apparently, the Gallagher advanced the throttle to position 4 for 38 of those seconds, increasing the train speed from 8 to 21 mph.

The locomotive engineer began the acceleration about 800 feet from the bumping block. Why?

The NTSB accident reports states:

He said he looked at his watch and noticed his train was about 6 minutes late arriving at Hoboken. He stated that when he checked the speedometer, he was operating at 10 mph upon entering the terminal track.

Six minutes? Ring a bell does it? Like more than 5 minutes? Like more than 5 minutes and 59 seconds—and classified as a late train?

Why? Because he didn’t want his train to be classified as a late train.

Sleep apnea may have caused him to lose conscious awareness of his surroundings, but the decision to advance the throttle and exceed the authorized speed was a conscious decision.

The importance of determining the root cause is that it determines the path of positive prevention.

In its regulation of PTC requirements, FRA has granted railroads the opportunity to apply for a Main Line Track Exclusion Addendum (MTEA), exempting the designated tracks from PTC requirements, if approved. Passenger train terminals are specifically identified as areas where FRA will allow MTEAs provided the maximum authorized speed for all movements is not greater than 20 mph, and that maximum is enforced by the on-board PTC equipment.

Hoboken proves not that MTEAs should be prohibited, but rather 1) 20 mph is too great a speed to allow a train to operate without automatic overrun prevention, and 2) passenger railroads will have to adapt their PTC systems to prevent end-of-track overruns.

The 20 mph can be reduced to 10 mph by an “electronic gating” process. As a train leaves PTC territory, the onboard system automatically enforces a 10 mph maximum until reentering PTC territory. Reducing the speed by half reduces the energy of a collision by three-quarters.

Moreover, passenger railroads can install “virtual” stop signals at the end of platform tracks, utilizing transponders, or wayside interface units (WIUs), to communicate distance to the “virtual” stop, and enforce a braking requirement to that distance.

Does this involve extensive and expensive work in passenger terminals? Of course. What doesn’t? But it’s better than bringing the roof down on somebody.

For further insight on OSA, see Bill Keppen’s editorial.

David Schanoes is Principal of Ten90 Solutions LLC, a consulting firm he established upon retiring from MTA Metro-North Railroad in 2008. David began his railroad career in 1972 with the Chicago & North Western, as a brakeman in Chicago. He came to New York in 1977, working for Conrail’s New Jersey Division. David joined Metro-North in 1985. He has spent his entire career in operations, working his way up from brakeman to conductor, block operator, dispatcher, supervisor of train operations, trainmaster, superintendent, and deputy chief of field operations. “Better railroading is 10% planning plus 90% execution,” he says. “It’s simple math. Yet, we also know, or should know, that technology is no substitute for supervision, and supervision that doesn’t utilize technology isn’t going to do the job. That’s not so simple.”