Gulf Coast Battle: A Possible Solution

Written by Jim Blaze, Contributing Editor

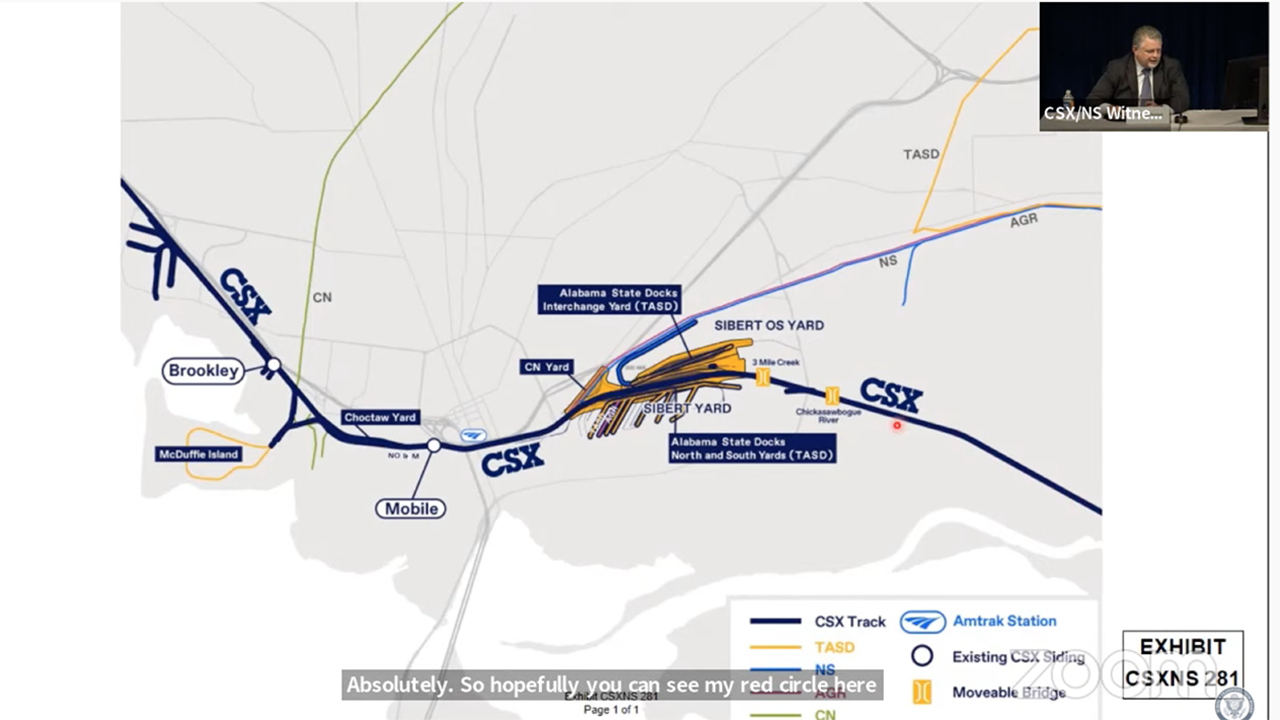

As the evidentiary hearing regarding the reintroduction and expansion of Amtrak passenger train service between New Orleans and Mobile continues before the Surface Transportation Board, interesting operational cost-sharing questions have emerged regarding how Amtrak trains may be able to coexist with very long CSX freights.

As background, CSX Senior Vice President Mechanical and Engineering Ricky Johnson testified about how CSX operates its freight trains on the New Orleans-Mobile route. His testimony was structured to identify why the recent changes to CSX’s business model conflicts with Amtrak’s desire to operate two daily round trips on this CSX right-of-way.

During the past three years, CSX changed its freight operating plan model to what it calls “a more precision-like freight train schedule,” translated as PSR (Precision Scheduled Railroading), an acronym people seem to either love or hate. But upon a closer review, it doesn’t seem to be either scheduled or anywhere near predictable, let along precision-like. It is, however. more complex.

This section of CSX main line has a fundamental trains-per-day capacity limitation. The opportunity to pass one Amtrak short train forward of another train, or past an oncoming train, is limited by the number and placement of passing second tracks (passing sidings) and their length.

On this route, the basic passing sidings are only about 8,500 feet long. But the newer CSX trains might occasionally be much longer. How much? About 10,000 feet, perhaps considerably longer. They are so new and so different to this track section that CSX’s witness called them “non-clearing” trains. If CSX runs non-clearing trains—say from Mobile, Johnson told the STB—then they plan the meets so that everything coming out of New Orleans is a clearing-capable train.

Amtrak trains are relatively short and therefore could be defined as a “clearable” train.

Why did CSX change its train length model?

Freight railroads do have the right to periodically change their operating model as they see fit. Nothing in the original Amtrak legislation limited rail freight business flexibility. And the STB has never really been in the role of dictating a different business model to regulated freight railroads, at the train operational level. Nevertheless, the STB does have the opportunity to ask CSX for solutions that could still offer Amtrak the possibility of passing such longer freight trains. Those kinds of options can be tested by the consultant that is running the RTC (Rail Traffic Controller) simulation modeling used by CSX in this ongoing dispute as a quantifying tool.

Here are two logical questions to guide the STB review process. But STB needs to ask for this insight.

- First question: Does the RTC simulation model identify the marginal cost benefit provided by mixing periodic much-longer freight trains over a physically restricted track network? Let’s consider that kind of a mathematical simulation as a base line toward discussing the cost associated with the freight change. And the marginal benefits? The purpose is to understand the marginal efficiency gained.

- As a second base line, the STB needs to ask about the reasonable financial costs to install either 1,500 linear feet of track so as to create a 10,000-foot passing siding at perhaps three locations along the Amtrak-proposed route. A reasonable historic look at similar field projects would assume perhaps $2-$3 million at each such location. For purposes of allowing for future possible longer CSX PSR freight trains, STB might ask CSX to have its modeling consultant run a costing assessment at 15,000 feet and use an assumed higher capex budget of $3-$6 million at each such site.

- The possible locations for placing such lengthened passing sidings could be based upon a review of CSX dispatcher sheets to estimate practical locations where the Amtrak and the longer freight trains might meet, based upon previous CSX longer-train movement records over this specific route. STB should ask about such insight.

The exercise is not a search for the “perfect” location and resulting project cost. It is instead a test for approximate best passing location patterns, reasonable capital costs for the increased lengths, and the improvement in network fluidity for Amtrak—plus some possible incremental improvement for CSX.

If three sites can be selected and then built, the approximate budget costs would range from a low of $6 million-plus for 1,500-track-foot extensions, up to as much as $18 million using 6,500 feet to gain a series of three 15,000-foot passing tracks. Add in a possible 20% 2022-23 project timeline, and the STB and the parties now have a logical capex execution plan for a practical passing track solution. Not perfect, but at the very least the basis for a reasonable discussion on a sidings solution. Add in an RTC model run with random likely “bad train meets,” and the parties can then discuss the likely excessive Amtrak delay pattern. They can use these iterations to agree upon a reasonable physical and cost/benefit tradeoff.

As to who pays, federal Amtrak legislation always assumed that the railroads, as of the creation timeline back in the late 1960s, would have excess track capacity. It was, after all, the period of heavy abandonments. But it didn’t turn out that way.

Nevertheless, the fee for Amtrak’s continued use of host freight railroad tracks was to be avoidable costs. To an economist, that generally is computed as medium-timeline cash-like costs and the avoidance of adding any capital-cost capacity to the older existing infrastructure. However, when capital dollars have to be added to create capacity for handling Amtrak needs, economists and engineers typically define such Amtrak physical needs as “fully allocated costs.” There are numerous examples of negotiated fully allocated cost projects across the U.S. for freight/passenger shared projects that support this adjustment to the original surplus-capacity avoidable cost solution.

The opportunity here is for the STB to both order as well as help both CSX and Amtrak to continue to rapidly find perhaps several correctly balanced solutions. This requires that the STB ask the parties the correct questions about testing for reasonable approaches. At this point in the evidence gathering, there are definite hints as to practical solutions without the need for the STB determining one specific “winner.”

The parties are close—but not yet at the finish line. The STB needs to keep pressuring with good technical probes. It doesn’t need to pick the answer itself. Helping the parties find their preferred negotiated solution is not over-regulating.

Another Viewpoint

I share with you the opinions of one veteran industry observer, for what it’s worth:

“A question I always have asked is how one or two daily passenger trains can be so disruptive of freight operations. CSX fought against Virginia Railway Express operating over the former RF&P route north into Washington D.C., but since allowed expansion of that service without any demonstrated negative impact on CSX freight operations. And when CSX wants to run a ‘business’ train for potential customers, there seems to be no difficulty, no matter the route.

“At a recent hearing, Amtrak’s counsel presented evidence that CSX spends at least $2 billion in capex annually for its entire network, but close to $500 million from Amtrak just for the Gulf Coast line to accommodate Amtrak’s trains. Amtrak’s counsel also brought out that CSX ran 20 through trains per day on this line in 1995-96, but is apparently running only eight today, albeit with more local trains, knocking down CSX’s argument that the line cannot accommodate more trains.

“But there is a bigger question: Why would CSX and Norfolk Southern risk poking the Ranking Republican on the Senate Commerce Committee, Roger Wicker of Mississippi, in the eye over this new Amtrak route, which he strongly supports, when they require his ‘good friendship’ on so many more important issues. Wicker will likely be Commerce Committee Chairman next year if Republicans regain Senate control. Ditto STB Chairman Oberman and member Karen Hedlund, both strong advocates of Amtrak, when their ‘good friendship’ is needed on freight regulatory issues tied to service, routes and mergers—especially the pending CSX acquisition of Pan Am. What are they thinking at CSX in annoying an STB where there almost certainly are three votes in favor of Amtrak and which holds the fate of CSX’s merger application with Pan Am (especially attached conditions) and the fate of the Reciprocal Switching rulemaking? Or are they thinking at all beyond seeking to extract from Amtrak taxpayer dollars—and then having the temerity to attack public subsidies to competing truckers. Indeed, STB on April 7 announced it is summoning the leaders of the ‘Big Four’ Class I’s—Jim Foote (CSX), Katie Farmer (BNSF), Alan Shaw (NS) and Lance Fritz (Union Pacific—to a public hearing later this month to discuss service problems.”

Independent railway economist and Railway Age Contributing Editor Jim Blaze has been in the railroad industry for more than 40 years. Trained in logistics, he served seven years with the Illinois DOT as a Chicago long-range freight planner and almost two years with the USRA technical staff in Washington, D.C. Jim then spent 21 years with Conrail in cross-functional strategic roles from branch line economics to mergers, IT, logistics, and corporate change. He followed this with 20 years of international consulting at rail engineering firm Zeta-Tech Associated. Jim is a Magna Cum Laude Graduate of St Anselm’s College with a master’s degree from the University of Chicago. Married with six children, he lives outside of Philadelphia. “This column reflects my continued passion for the future of railroading as a competitive industry,” says Jim. “Only by occasionally challenging our institutions can we probe for better quality and performance. My opinions are my own, independent of Railway Age. As always, contrary business opinions are welcome.”

Editor’s Comment: The problem of freight trains that are too long for their sidings reminds me of Stan Kenton’s 1947 novelty calypso pop tune, “His Feet Too Big For De Bed,” a departure from the “Progressive Jazz” that Kenton and his very large (and very loud) big band was known for back in the day. It was sung by June Christy with Kenton’s short-lived vocal quintet, the Pastels, and augmented with Latin percussion. It bombed, no surprise. Here are the lyrics. – William C. Vantuono:

Ooh Da-doodle-ah-do-do Pow Pow Pow Pow!

He big man, she little woman

Look sad together but sure got plenty fun

He big man she little woman

Have matrimony and a medium son

His feet too big for de bed,

His feet too big for de bed

No can sleep double got plenty trouble

His feet too big for de bed

Ooh Da-doodle-ah-do-do Pow Pow Pow Pow!

He big and fat, she little and fat

He like big dog she like small pussy cat

Got no room for medium son

Send him to school for education

His feet too big for de bed,

His feet too big for de bed

No can sleep double, got plenty trouble

His feet too big for de bed

Stand on chair to trim his hair

He go to bed in his long underwear

Snore off-key and buzz like bee

She make him sleep in de coconut tree

His feet too big for de bed,

His feet too big for de bed

No can sleep double, got plenty trouble

His feet too big for de bed

Ooh Da-doodle-ah-do-do Pow Pow Pow Pow!