Still Riding, Still Writing at 75!

Written by David Peter Alan, Contributing Editor

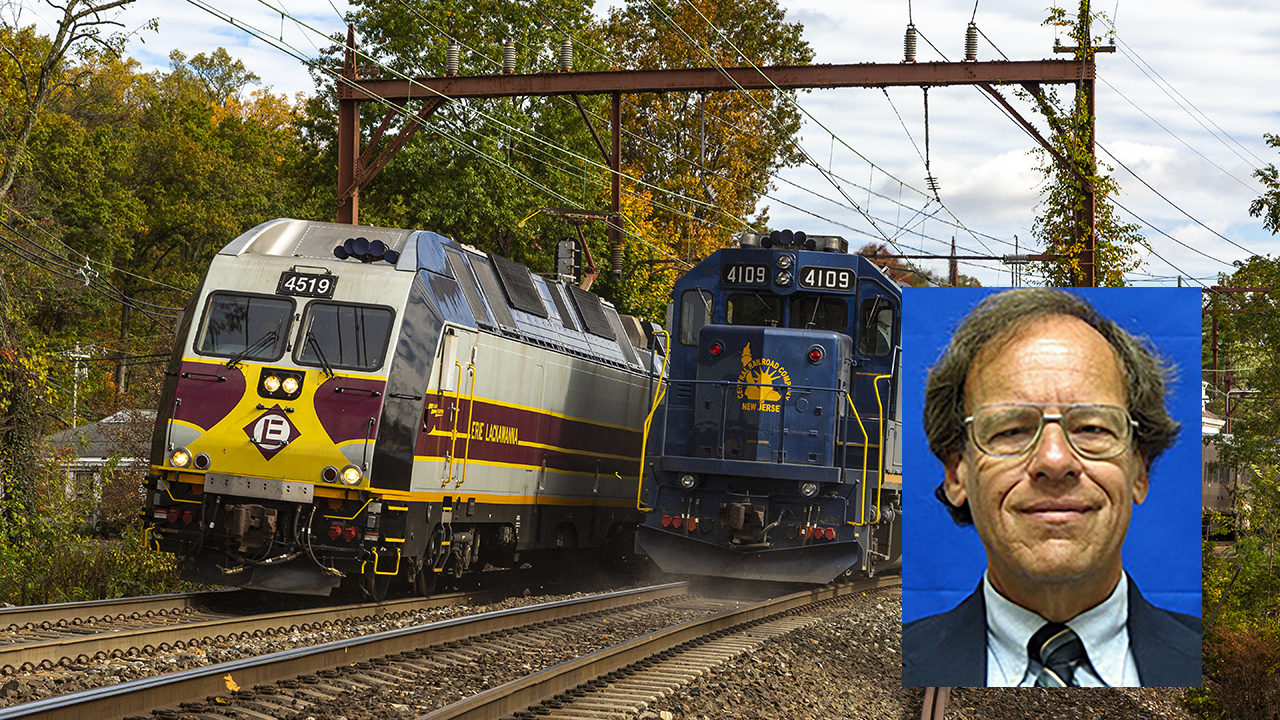

NJ Transit trains hauled by locomotives in heritage Erie-Lackawanna and Central Railroad of New Jersey schemes at Millburn, N.J. NJT main photo. Composite image: William C. Vantuono

Sometimes I find it difficult to believe that I’ve made it this far. Wednesday, March 8, is my 75th birthday. None of us ever know precisely how many more birthdays we will have, or in what condition we will be when we observe them, but I’m concerned mainly about how many more years I will be able to ride passenger trains and transit, to have the mobility to go places, and to write about those trains and places. So, as I review where not only I but other seniors stand, it’s time to share some thoughts and concerns.

Thriving Elsewhere, Just Not Here

Europe and Asia are full of trains and rail transit. People respect them and ride them. In that part of the world, a railroad man like Alexander Kamyshin, until recently the head of the Ukrainian railroads, is a national hero, and deservedly so. He is doing his part to help his country win a war that was forced on him and his fellow Ukrainians. But his country has no air service, and the locals know they need trains.

That’s not so in the U.S. or Canada. There are riders on the few trains we have, but there are so few trains that rail travel can’t make a dent in the massive numbers of airline passengers and, especially, motorists. The same goes for rail transit, except in about a dozen large cities in the U.S. and a few in Canada.

A Lifetime of Riding

I have depended on transit for all mobility throughout my life, especially my adult life. I grew up near New York City and went to an urban university (M.I.T.), so I developed an appreciation for transit, especially rail transit, early in life. I started advocating for better transit only 3½ years after I was admitted to practice law. I see my primary current activity, writing for Railway Age, as the culmination of a lifetime of riding trains and transit, and helping to improve mobility, not only for myself, but also for other people who ride, whether they depend on transit, or they are motorists who ride by choice.

Through the years, I have ridden on services run by more than 300 transit providers in the U.S. and Canada, including many community-transportation agencies that provide demand-response (call ahead) rides for people who need them, whether because of age, a disability, or another reason. That includes all rail transit in the U.S., and I have six more “new start” segments to ride before I can regain the distinction of having ridden all of it, which I held for 77 days in 2019. I have also ridden the entire Amtrak system and visited about 85% of Amtrak’s destinations (many of the others are along California’s Amtrak corridors), as well as about 50 places where Amtrak went in the past, but no longer. One of my greatest goals is to exceed one million miles on Amtrak, if Amtrak and I both last long enough. The follow-up to that statement is obvious. If one person can ride all the trains and rail transit in a country as big as the U.S., even with a concerted effort, there is not enough mobility on rails.

My “bucket list” now includes going to Alaska and Hawaii, the only two states that I have yet to visit. That means the Alaska Railroad in its entirety, and the White Pass & Yukon on the other side of the border. Elsewhere in Canada, there are a few routes that I have not ridden on VIA Rail, and two Native-owned (the Canadian term is “First Nations”) railroads in the far north. I hope to complete all of this during the next two summers. Beyond that, I hope to visit London and other places in Europe to get the flavor of their rail and transit networks, and to ride true high-speed-rail, which I doubt that I will be able to do in this country. We might have it someday, but probably not in time for me to ride it.

Plans, Plans and More Plans

When my contemporaries and I were young, we looked forward to better transit and more trains someday, as Amtrak survived beyond the “brief experiment” stage of the early 1970s. We saw a few systems emerge in that decade (BART in the Bay Area, MARTA in Atlanta, and Metrorail in the Washington, D.C. area), and we saw light rail come to the forefront in the 1980s and 1990s. Still, through the years, most of what we saw were plans, plans, and more plans. We can ride a train, a light rail vehicle or a streetcar, but we can’t ride a plan.

Famed Scottish poet Robert Burns first wrote “The best-laid plans of mice and men often go awry” (loosely translated from the original Scots dialect) in 1785, a half-century before the first trains appeared and a full century before transit as we know it was born. Yet it seems that the managers who plan transit improvements for us keep those improvements out of reach. Sure, they claim that new starts will run someday, probably toward the tail end of a planning frontier stretching 25 to 40 years into the future. The consultants that former NYMTA Chair Pat Foye called the “Transportation Industrial Complex” makes plenty of money doing studies, but nobody can get on board a study and go somewhere.

Lots of big rail plans have “gone awry” as Robert Burns warned. New York City planned the Second Avenue Subway more than 100 years ago, and an elevated line above that thoroughfare was torn down in anticipation of that proposed line. In all that time, all the “locals” got was an overpriced four-stop extension that is still called “The Second Avenue Stubway.” Will it ever extend downtown from the Upper East Side? Maybe someday, but we won’t live to ride it. New Jersey Transit proposed a series of projects in 2000 that would have delivered a more-extensive rail network by 2020. There were 13 proposed projects, but none of them were ever built. Instead, the agency concentrated on the Access to the Region’s Core (ARC) Project until 2010 and the current Gateway Program since 2011. Gateway is still billions of dollars and more than a decade from completion, and that date keeps receding into the future. Until it recently opened, the same could be said about the new East Side “Grand Central Madison” deep-cavern terminal on the Long Island Rail Road. It was originally slated to open for service years ago, it cost more than $11 billion that some journalists and advocates say could have been used to improve the subway system with better results, and initial ridership numbers have been disappointing. Will those numbers improve as managers tweak the schedules? Time will tell.

The problem is that mega-projects like those crowd out smaller projects that would be comparatively inexpensive but could actually improve mobility on a time frame that riders can anticipate. They could be built relatively quickly, which means riders would be able to point to a project that does some good for them, rather than hoping for a mega-project that might open for service after they have paid for it and maybe after they die. There is also a credibility issue. A longtime advocate who is older than I and still going strong says: “We have to plant trees, even though we won’t be around to sit under them.” There might be something to be said for that philosophy, but today’s riders and advocates know that many of the “trees they planted” never grew past the seedling stage, so many of us are skeptical.

A Shrinking Long-Distance Mobility Network

The nadir of American rail transit occurred when I was a young adult, in the 1960s and ’70s. The New York (including New Jersey), Philadelphia, Boston, and Chicago areas had major multi-modal rail systems. So did Toronto and Montreal, and San Francisco and a few other places still had some streetcar lines. There was not much else, as even the biggest cities had no transit other than slow city buses. All that decline was completed over a few short decades, as most Americans gleefully took to the highways and left the non-motorists in their midst behind, at the bus stop and everywhere else.

I have ridden many “last runs” of rail transit lines and on train routes since my undergrad days in the late 1960s, although there have been a few “first runs” on new-starts. Transit is coming back, but at a glacial pace. A few cities like Los Angeles and Denver have embraced it, but most have not built more than a token line, or anything at all.

Since it was founded in 1971, Amtrak has been consistently unwilling to allow its network to expand significantly. Its long-distance network is the same size as it was then, 14 trains in each direction, not counting the Auto-Train, which non-motorists are not allowed to ride, except while accompanying the owner of the vehicle that is the official “passenger” on the train. Even at that, the few remaining long-distance trains appear to live in a constant state of jeopardy. Today they suffer from short consists and crew shortages, and it seems difficult to believe that the long-distance network five years from now will resemble the one today, if it even exists at all. The long-distance “network” on VIA Rail in Canada looks more like a cruel joke. The transcontinental Canadian between Toronto and Vancouver (named for its equipment, rather than for its route) runs only twice a week, and it provides a “rail cruise” for sleeping car passengers that still evokes the “Golden Age” of rail travel, the experience of rolling through the countryside on venerable equipment that survives from the halcyon days of trains. The Ocean between Montreal and Halifax runs equally infrequently, without delivering the experience. VIA Rail’s other trains serve other purposes, and none of them run more often than three times a week.

While we seldom write about buses here at Railway Age, they do constitute a part of a non-motorist’s mobility network, a part that is shrinking faster than the rail segment. Now that the German company Flixbus has absorbed it, Greyhound Lines has been shedding stations at a rapid pace and requiring riders to wait on street corners, as if they were catching a local bus. Greyhound buses no longer stop at a growing list of cities and towns. Tourist mecca St. Augustine, Fla. (the oldest town in the country inhabited continuously by non-natives) is one. Jackson, the capital of Mississippi, is another. The latter is still served by Amtrak (the City of New Orleans), but the former has not had such a train since 1968. While the intercity bus presence in the U.S. has shrunk dramatically in recent years, the demise of the former Canadian network is almost complete. Greyhound Canada died during the COVID-19 pandemic, and there are almost no intercity buses left in the entire nation. The few coaches on VIA Rail’s long-distance trains can’t accommodate many people, so most non-motorists go nowhere.

Corridors Hang In, But For How Long?

The growth on Amtrak has been in state-supported trains and corridors. California and Illinois are the pacesetters, while other states like Washington, New York, Pennsylvania and North Carolina have established at least a single route that runs three times a day or more in each direction. The Northeast Corridor (NEC) remains strong, but most trains that run there are operated by regional agencies like New Jersey Transit and SEPTA. Whatever financial problems the NEC might have, it would be essentially impossible to build enough highways to accommodate the riders on Amtrak and on the local railroads in the region. In Canada, the corridors that VIA Rail operates keep going, but they cover only a small portion of the country’s geography, centered on Montreal, Toronto and Ottawa. That is probably the most-populated area of the country, but nobody has ever proposed a corridor elsewhere in Canada, like between Vancouver and somewhere else, but where would that “somewhere else” be? Looking ahead, it does not appear that many changes on VIA Rail’s corridors seem to be in the cards.

In terms of service, there will probably not be many changes on the NEC in the foreseeable future, either. There might be some changes in management, though, especially if losses to Amtrak’s skeletal long-distance network and state-supported trains and corridors turn Congress and other elected officials against “America’s Railroad.” There are two investor-funded proposals on the table. One is RAILnet-21, which proposes an Infrastructure Management Organization (IMO) that would manage the NEC and lease trackage rights to potential train operators, including Amtrak and the regional railroads that now operate on the Corridor. The other is AmeriStarRail, which proposes an enhanced operation on the NEC and its branches that would be compatible with Amtrak ownership or ownership by another entity. Even if Amtrak is forced to “go regional” and stay in the Northeast, the states could negotiate an interstate compact to run the railroad. That could even be done through the existing Northeast Corridor Commission.

It would probably be a different story for corridors elsewhere. Those corridors skew toward “blue” states, and some run in “purple” states. State transportation departments could keep corridors going within the state’s borders, and maybe into a neighboring state. It seems difficult to believe that, even without Amtrak, California and Illinois would eliminate their corridors, New York State would give up the Empire Corridor, or Pennsylvania the Keystone Corridor. Virginia is spending money to improve its passenger rail infrastructure without interfering with freight, and running more trains on it. The future of corridors in other states might not be so clear. Funding is an issue now, and it will always be an issue.

Amtrak has proposed more than three-dozen routes that would be established by 2035 in its ConnectsUS plan. While many planners, managers and advocates are encouraged that Amtrak has even dared to dream about more trains after so many decades of status quo or even retrenchment, it is not at all clear how many states will have the money, or even the volition, to fund new passenger rail routes. After a long battle, passenger trains will return to the route between New Orleans and Mobile relatively soon. It is reasonable to expect that some other states will pay for new corridor-length routes proposed in the Amtrak plan, but times are hard for many states, so there will probably not be many such routes.

A Fiscal Cliff

The future of rail transit and maybe even the future of bus service is precarious almost everywhere. Ridership everywhere has declined since the COVID-19 virus struck three years ago. Ridership is recovering, but it has not reached pre-COVID levels, and it appears unlikely to reach those levels again, at least not in the foreseeable future. As I have been saying since July 2020, the five-day commuting model in effect before the virus attacked is now history. Times have changed generally, and that includes work patterns. While many employees are going back to the office, not all of them will spend five days there every week. Maybe two or three, but not five. That means “commuter railroads” will need to position themselves as “regional railroads” and run more trains outside historic commuting hours. It also means that ridership everywhere on transit has decreased, since there are no longer as many trips to the office as there used to be. Transit managers must now devise innovative solutions.

The feds have given a portion of the nation’s COVID relief funds for operating support to keep transit going. It was a necessary step, as ridership plummeted everywhere. While I have endorsed that practice, elected officials disagree. Those funds won’t last long, and a disaster is looming. New York’s transit is the proverbial canary in the mine shaft, as transit officials are asking even the City of New York to kick in more money that it probably can’t afford. NJ Transit is not far behind New York in line to feel the pinch. Recently, BART has raised the alarm. It’s really a universal catastrophe in the making for transit.

If nothing is done, the results will probably be disastrous. In cities like New York and St. Louis, where local financial problems in the past hit the transit systems hard, the result was massive service cuts. Non-motorists suffered, and some were finding it impossible to get around, especially if they lost their bus route and there was no other nearby. People stayed away from transit with its reduced service, filling up the highways and jamming them with traffic, as the vicious downward spiral continued to make the situation worse. It took cities and other areas within their service areas a long time to recover. Today, many transit providers have not recovered from the sharply decreased ridership wrought by the virus. Will they weather the coming storm? Time will tell, but all of them are in for a severe challenge.

All Not Lost, Not Yet

If elected officials and transit managers sit complacently and refuse to anticipate the coming disaster, the result will be a catastrophe. It’s not too late, though. It’s time for action. Elected officials must somehow recognize that not only motorists need mobility, and that federal, state, county and municipal officials have an obligation to ensure that everybody has a reasonable amount of mobility, whether or not they have access to an automobile. They need to abandon their historic custom of ignoring advocates for train and transit riders and recognize the roughly 15% of American adults who are not motorists as deserving to go to some places, too. The advocates need to push the hardest, because their (our) basic mobility is at stake.

If you decide to fight to keep as much of our non-automobile mobility as possible, you must be vocal, and you must convince elected officials and business leaders of the importance of transit and passenger trains to your communities, especially to the economies of those communities. While I understand and support the environmental arguments and the “social equity and justice” arguments, those are not the messages that every decision-maker is willing to hear. Some Republicans hate Amtrak and despise transit, and nothing will convince them. Not all are like that, but not all politicians care about those issues. Everybody cares about the economy of the places they represent or where they live. Democrats and Republicans alike want to see their constituencies thrive and prosper, and transit managers and rail advocates can deliver the message most effectively.

My Future Plans

At this writing, I have plans for extensive travel on Amtrak this spring, to present at a rail conference in California late in May, and to return home through Canada in late May and early June, including rides to Churchill, Manitoba other obscure places on VIA Rail. I plan to file some trip reports, as well. I also plan to ride the few new transit starts that I have not yet had the opportunity to ride, and to report about them. Brightline might be running revenue service to Orlando Airport within the next few months, too.

Against that backdrop, the political and economic hurdles that Amtrak and our transit systems must face in the coming years will be truly formidable. That seems to go for VIA Rail and transit in Canada, too. Will the people who make the decisions care enough about the folks who are not sufficiently fortunate that they can also operate a vehicle, and allow the nation’s non-motorists to retain a semblance of mobility? We can hope so, but we must also do more than that. Otherwise, my age cohort, including me, might not be able to make so many travel plans when we turn 80, if we last that long.

That seems to be the point. At this age, we don’t know how long we will be not only still alive, but also still active enough to do things. In my case, that includes riding trains and transit, and reporting to you about what is happening to them. It is ironic that, when I was 70 and started writing for Railway Age, I began to consider myself as an “elder statesman” in the rider-advocacy movement, where I head learned much of what I now know about the railroad and about transit. Given the ages of most of the other advocates, I was probably below the median age at that time. By now, I have probably gotten into the older half of the membership by now, which means that movement is facing a crisis, along with the trains and transit they defend. If and only if the movement can attract enough younger people, it will survive.

Personally, I plan to keep riding and keep writing for as many years as I still can. It is my remaining hope that there will still be more trains and more transit for me and everybody else to ride.

David Peter Alan is one of America’s most experienced transit users and advocates, having ridden every rail transit line in the U.S., and most Canadian systems. He has also ridden the entire Amtrak network and most of the routes on VIA Rail. His advocacy on the national scene focuses on the Rail Users’ Network (RUN), where he has been a Board member since 2005. Locally in New Jersey, he served as Chair of the Lackawanna Coalition for 21 years, and remains a member. He is also Chair of NJ Transit’s Senior Citizens and Disabled Residents Transportation Advisory Committee (SCDRTAC). When not writing or traveling, he practices law in the fields of Intellectual Property (Patents, Trademarks and Copyright) and business law. The opinions expressed here are his own.