BART: Power of Art in Times of Tragedy

Written by Bay Area Rapid Transit Communications Department

The memorial at the San Bruno BART Station plaza based on a Dorothea Lange photograph of Mochida sisters departing for incarceration at Tanforan. (Photograph and Caption Courtesy of BART)

“It’s incredibly important to keep this history alive because, even though it happened 80 years ago, with Executive Order 9066, it’s still a history not everyone knows. It hasn’t been covered extensively in the history books. This exhibition is a place for remembrance and acknowledgement, education and healing.” —Na Omi Judy Shintani, Curator, “Tanforan Incarceration 1942; Resilience Behind Barbed Wire”

In 1942, following the issuance of Executive Order 9066, the U.S. government incarcerated more than 120,000 people of Japanese heritage, 8,000 of whom started their imprisonment at the Tanforan detention center on the site of a repurposed racetrack in San Bruno, Calif. The hastily whitewashed stalls, the barracks, and the grandstand served as the incarcerees’ living quarters. Even with a fresh coat of paint, a pervasive stench of horses and manure remained, and barbed wire fences and armed guard towers ringed the perimeter.

Today, the Tanforan shopping center and adjacent San Francisco Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART) District station occupy the site of the former detention center. The tragedies that occurred there have not been forgotten.

In August, a new memorial and exhibition were unveiled at Tanforan to commemorate the tragedy that occurred there and the fierce resilience of the prisoners, 64% of whom were U.S. citizens.

Outside the San Bruno BART Station is a powerful memorial created by the Tanforan Assembly Center Memorial Committee. The centerpiece of the memorial is Sandra Shaw’s bronze statue of two little girls, suitcases in tow. There is also a replica horse stall one can walk through and a memorial wall with the names of the 8,000 incarcerees. The monument is punctuated by poetry by incarcerees.

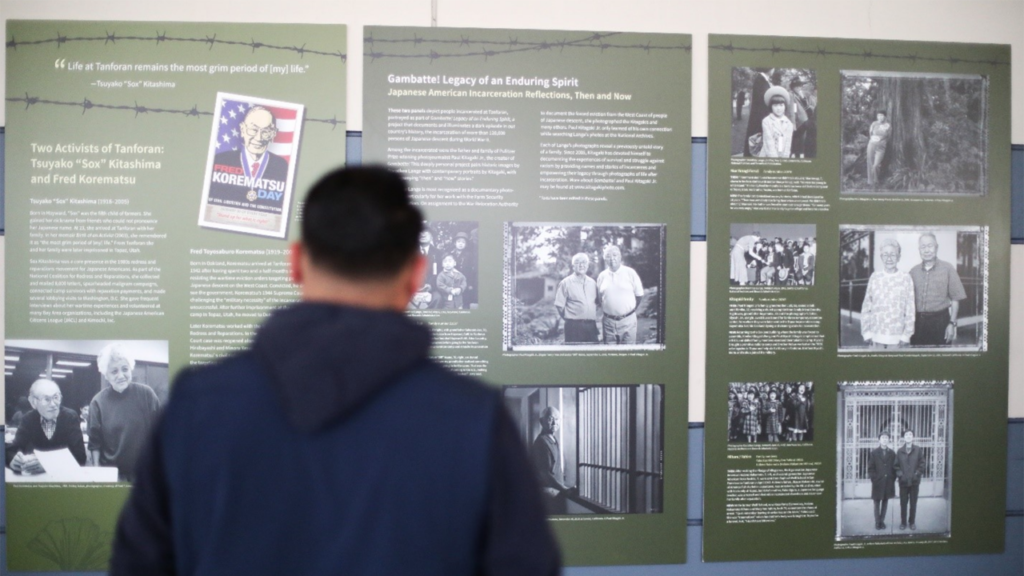

Inside the BART station, a new exhibition, “Tanforan Incarceration 1942: Resilience Behind Barbed Wire,” covers the walls to the right of the station agent booth. The exhibition was organized by the BART Art Program and curated by artist Na Omi Judy Shintani. Carole Jeung designed the panels. “Resilience Behind Barbed Wire” replaces a previous installation of photographs created by Dorothea Lange and Paul Kitagaki Jr. (Some of Lange’s and Kitagaki’s images remain in the current exhibition.)

Shintani connected with BART through the Asian American Women Artists Association. In addition to being a skilled curator, Shintani is also an artist who has created many works about Japanese incarceration. Japanese American incarceration is highly personal for Shintani, as well; her mother’s father and father’s family were incarcerated at Japanese concentration camps, she said.

Shintani wanted the 16 panels of the exhibition to educate, as well as illuminate, the creativity and resilience of the people incarcerated at Tanforan.

“I feel people get a full picture of what happened, how the people were feeling that were there,” she said by phone recently. “…You can say 8,000 people were incarcerated, but who were they as individuals? That’s what I wanted to bring to light, some of the personal stories that people can relate to even if they’re not Japanese Americans.”

In her curation, Shintani not only included art made by people incarcerated at Tanforan, but also contemporary pieces from incarceree descendant artists whose work connects to this history—the next generation.

Shintani thinks the exhibition can be “very healing” for generations of families of Japanese descendants who were unjustly imprisoned. “It’s a very moving exhibition,” she said. “I think it’ll bring up lots of emotions for people.”

A BART station may not be the first place you expect to find such a profound exhibition, but that is, in some ways, the point.

“Horse tracks go away, but this was a place where people were forced into a situation none of their making,” said Art Program Manager Jennifer Easton. “You can’t erase that, nor should you.”

BART recognizes the power of what some scholars and activists call “trauma-informed placemaking,” which stresses the importance of spaces and interventions for collective grieving. While acknowledging that BART “had no culpability” in the incarceration, Easton said she applauds the BART Board of Directors for recognizing the importance of “allowing the land to be used for this.”

“It’s really something to be proud of,” she said.

Easton and Shintani also described the challenge—and delight—of designing such an exhibition for a BART station. Easton spoke of the “shared experience” of being a transit rider; one is literally required to interact with others when taking public transportation. There is magic in that.

“You’re creating this sense of commonality in that experience,” Easton said.

Shintani touched on the more practical aspects of installing such an exhibition in a BART station. Public access, vandalism, durability and “bird poop” were all hurdles to overcome. She said the panels are large, colorful and dynamic to “hopefully stop someone at some point during their trip.” Additionally, Shintani and Easton are working on a website that delves into the history of Tanforan and its aftermath, as well as an augmented reality feature that animates and brings another layer of experience to understanding this history.

“It’s going to make it really accessible for people in the Bay Area, for people to have a place to go as a sort of family pilgrimage, and for school field trips to learn more about incarceration,” Shintani said. “It’s going to be a special place that will be here forever.”

The memorial is free and open to the public and is accessible at any time. The exhibit is accessible to anyone arriving by BART. If you are arriving to the station by another mode of transit, you may ask the station agent to allow you admittance to see the exhibit without purchasing a ticket. This is at the discretion of the station agent. If you are part of a group (more than five) that wants to visit the exhibit and are not arriving by BART, please contact [email protected], at least 10 business days in advance, with the date and time of your visit and approximate number of visitors so arrangements can be made.

The exhibition was funded, in part, by grants from the U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, Japanese American Confinement Sites Grant Program, and California Humanities.

This article first appeared on the BART website.