Private Sector Investment in NEC Operations?

Written by David Peter Alan, Contributing Editor

For almost half a century, passenger rail service in the United States has resided in the public sector. Despite its unusual statutory charter, Amtrak’s voting shares belong to the U.S. Department of Transportation. Every transit agency that runs trains in its metropolitan area is owned by some sort of public entity, whether based in state or local government, or a separate public-sector authority. Times are changing, though, and certain private-sector entities have expressed interest in running passenger railroads.

The best-known case in point is Brightline in Florida, which is extending its range north of South Florida’s commutershed, to Orlando Airport. The company’s proposed Las Vegas operation, XpressWest, is also moving forward, working on getting funding for its proposal, and looking toward a means for connecting into the Los Angeles area.

Private-sector entities are also eyeing Amtrak’s Northeast Corridor (NEC), in terms of managing the NEC’s operations and infrastructure. In this article, we will explore a proposal for managing train operations along the NEC and its branches.

In the past, it seemed that everybody assumed that Amtrak would keep operating the country’s busiest passenger rail corridor, while continuing to own it, as well. In light of recent developments, mostly spurred by the COVID-19 pandemic, that assumption may no longer be solid. By statute, Amtrak consists of three components: the long-distance network, state-supported trains and corridors outside the Northeast, and the NEC and its branches. “America’s Railroad” has historically been held together by a political understanding: Members of Congress from states that hosted a train or two on the long-distance network supported Amtrak in order to keep those trains, while much of Amtrak’s authorized funding went to maintain and operate the NEC, which comprises most of the Amtrak-owned infrastructure. Members from the Northeast Region strongly support Amtrak because of the NEC, and seem to understand that keeping a few trains running elsewhere assures political support from those other places.

Amtrak now plans to reduce every long-distance train (except the Auto-Train, which is not available to passengers without an automobile) to operating only three times a week, and many connections that are temporarily available every day will be available even less often. That could spell the end of the political support for Amtrak outside the Northeast and, consequently, the demise of the alliance that brings in the money, which now keeps the NEC going.

So it may now be time to consider private-sector proposals for funding operations and infrastructure on the NEC and its branches. In this article, we will explore such a proposal for operations. It is offered by AmeriStarRail. and according to Scott R. Spencer, the company’s co-founder and Chief Operating Officer, it is “infrastructure agnostic” in that its operating model could be applied if Amtrak continues to own the NEC infrastructure, or if another entity takes it over.

The company’s vision of “High-Speed Rail for All” is described this way: “The AmeriStarRail (ASR) proposal will expand Amtrak’s Northeast Corridor (NEC) capacity to meet travel demand for the next 20 to 40 years. Our solution eliminates issues and challenges surrounding travel congestion in the Northeast Corridor without the environmental consequences of building more highways and airports.”

“We’re focusing on a business model for all costs above the rails, Spencer said. “We market and ticket trains as Amtrak trains. We provide crucial private investment to make these innovations possible.” He added that it was his dream “to achieve the holy grail of the railroad industry, which is running passenger trains profitably.”

Spencer and his colleagues at AmeriStarRail, including former Amtrak President Paul H. Reistrup, believe they can do just that. Spencer summarized the proposed method: “Our better way is achieved by driving innovation in four key areas: service, marketing, technology and operations.”

One of the core features of the plan is to eliminate terminal operations for NEC trains at Washington D.C., Philadelphia, and New York. The key would be through-running. There is nothing new about recommending such an operation in New York City; it has been proposed by the Institute for Rational Urban Mobility (IRUM), ReThinkNYC and a number of other local advocates individually. The AmeriStarRail plan takes the concept further, and introduces through-running further south. Spencer points to potential efficiency improvements in equipment and crew utilization, new marketing opportunities, and freeing tracks at major stations for local rail services as potential benefits of through-running, as well as getting NEC trains out of Ivy City Yard in Washington and Sunnyside Yard in New York. He said the plan would result in “unlocking the NEC” and would offer “triple-class service” on every train, as opposed to Amtrak’s current Acela trains, which offer only the two premium-fare classes.

The “routes and maps” section of the plan’s website contains an array of maps that detail the company’s proposed operations, from extensions of the current spine of the NEC to track changes at Penn Station, New York.

DOWNLOAD A PDF CONTAINING ALL MAPS AND DIAGRAMS:

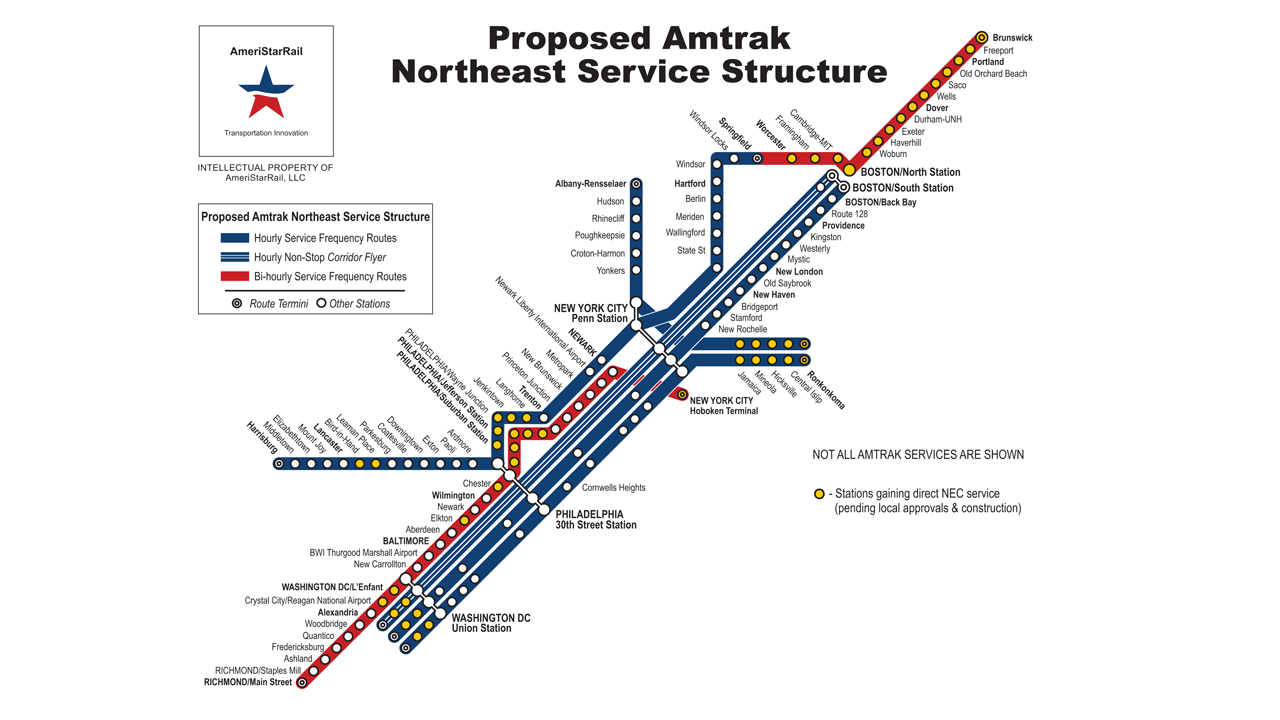

The basic stick map (Map 1) shows extensions and branches that would be added to the basic spine. The overall plan calls for new operations to Richmond, Harrisburg, Albany, Hoboken, Ronkonkoma, and a twist on the old Springfield Line to Boston. Trains would run from New Haven, through Springfield, bypassing South Station and stopping at North Station in Boston, and continuing on the Downeaster line to Maine.

The proposed route structure is shown in Map 3. The NEC itself would be extended south to Alexandria, Va., where most northbound trains would originate. That feature would be implemented in the future, after the new span of the Long Bridge, a project sponsored by state authorities in Virginia, is completed. Hourly “Non-Stop Corridor Flyer” trains would only stop at Washington, D.C. and New York on the way to Boston. There would also be hourly trains making the additional stops that most NEC trains make today.

Three other hourly services would use new routes. One would run from Alexandria to Penn Station New York and onto the Main Line of the Long Island Rail Road (LIRR) to Ronkonkoma. Another would originate at Harrisburg, run along the Keystone route to Philadelphia, take a new route to Trenton and the current NEC to New Haven, and then go to Springfield, Mass. on the recently upgraded Hartford Line. The new route is shown on Map 6. Trains would use SEPTA tracks to go most of the way to Trenton, through Suburban Station and onto the West Trenton Line, historically part of the Reading Railroad and now one of SEPTA’s regional rail lines. There would be a new connection using CSX track east of Langhorne to the Trenton station on the NEC, so trains would go there instead of to West Trenton. The other new service would involve through-routing at New York Penn Station between two lines that never saw such an operation before: Trains would start on the Empire Corridor at Albany-Rensselaer, go through connecting tracks at Penn Station, and proceed to Ronkonkoma on the LIRR Main Line (Maps 7 and 8).

The plan also calls for two entirely new and novel operations with service every two hours: one from Springfield to Maine, and the other from Richmond to Hoboken, N.J. Some trains originating at Harrisburg and traveling up the Hartford Line to Springfield would continue eastward on a through-running operation toward Boston and Maine. They would not go to Back Bay or South Station, but onto the Grand Junction Railroad, west of them. There would be a new stop in Cambridge, behind the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) campus, and trains would then proceed to North Station. The MBTA (the “T”) uses that stretch of track to shuttle equipment between its Northside and Southside services, and using it for scheduled service is not a new idea, although it has never been done. (Personal note: Future engineer and planner Bruce Horowitz first suggested it to this writer more than 50 years ago, when we were undergrads together at MIT). Beyond North Station, the trains would run to Maine, on the current Downeaster route.

The other proposed bi-hourly route would originate at Main Street Station in Richmond, in the trendy near-downtown neighborhood of Shockoe Bottom. The trains would make semi-local stops on the NEC to Philadelphia and proceed over the former Reading route through Jenkintown to Trenton and back onto the NEC to Newark, east to New Jersey Transit’s Kearny Junction, and then on NJT’s Morris & Essex Line into Hoboken Terminal. The last time a scheduled train (not counting occasional excursions) left Hoboken and traveled beyond NJT’s commutershed was in 1970. Hoboken is a major transfer point, offering connections to several NJT rail lines otherwise unconnected to the NEC, NJT light rail and local bus lines, and ferries and PATH (Port-Authority Trans Hudson) trains to New York. Spencer told this writer that the plan would add “remarkable utility” to Hoboken. Many advocates in New Jersey would agree, as they have complained for years that Hoboken is currently underutilized.

There are intermodal components to the plan, as well. Some riders could use the growing network of ferries around Hoboken and New York City for the “last mile” segment of a trip. Spencer also said that AmeriStarRail would also operate a number of shuttle buses, especially to airports near the rail lines. There would be other shuttle buses, too: between Penn Station and Grand Central Terminal in Midtown Manhattan, between North and South Stations in Boston, and between Metropark and Arthur Kill Station on the Staten Island Railway (SIR) Line, which Spencer says could save two or three hours of travel time currently needed to get a three-seat ride to or from Penn Station (SIR, ferry and subway).

Spencer also talked about an inexpensive plan to modify Penn Station New York for through-running. Tracks 10 and 13 would be removed from service, thereby making Platforms 5 and 7 wider. Spencer said those tracks would not be needed for the operation, and suggested leaving flatcars at floor height on those tracks, so it would not be necessary to remove the tracks completely (see Map 11 for an overhead view and Map 12 for a cross-section and diagram of passenger flow). Certain stairways or escalators would be used for passengers descending to platform level, while others would be used to ascend from it after getting off the train. In that way, according to Spencer, a New York stop could take as little as two minutes. Through-running would also ensure enough capacity at Penn Station that there would be room for the LIRR and for New Jersey Transit’s local trains, without having to build such new infrastructure as the proposed Penn South Station that is part of the massive Gateway Program, a controversial addition that would leave commuters further from their offices and all riders further from connecting subway lines.

Other members of the AmeriStarRail team include J. William Vigrass, consultant and former Assistant General Manager of PATCO, a metropolitan-style “heavy rail” line that runs between South Jersey and Philadelphia, and attorney Neil B. Glassman. The best-known member is Reistrup, who served as president of Amtrak from 1975 to 1978. During his tenure, he initiated the Northeast Corridor Improvement Program and ordered the Amfleet cars that still run on the NEC, as well as the Superliner equipment that still runs on the soon-to-be-slashed national network. According to the AmeriStarRail web site, Reistrup initiated the idea of through-running at Washington Union Station, and moving the NEC’s terminal to Alexandria. Reistrup said that other stakeholders, including potential investors and the railroads where the trains would run were “receptive” to the plan.

For his own part, Spencer became involved with through-running in the 1980s, when he worked on the project to join the historic Pennsylvania and Reading Railroad lines with the tunnel that now runs between 30th Street Station and Jefferson Station (formerly Market East) through Suburban Station as a planner at SEPTA, under the leadership of David Gunn (who was later also president of Amtrak).

Reistrup and Spencer ardently support the concept of through-running and tout the operational efficiency, added capacity, and other benefits that it can bring. One such benefit that they hope to deliver is faster travel time. The plan’s proponents believe they can accomplish running times of 1:59 between New York and Washington, DC and 2:59 between New York and Boston, which could mean beating five hours for the combination; those would be the running times for non-stop service. According to Spencer, the trains would feature other amenities: food service on every train (including Albany and Harrisburg), door-to-door baggage pickup and delivery, bicycle spaces, assigned seating for everybody, and possibly compartment-style seating as practiced on trains in Europe. The plan calls for these amenities to be available to coach passengers as well as riders paying premium fares. Spencer is promoting the environmental benefits of rail travel, too. As he says on the web site: “Trains are the most sustainable, climate friendly form of transportation. Go easy on the environment. Go by train!”

The plan’s team is looking for private investors and expect to find them, crediting their innovations for attracting private capital. They expect that farebox revenue will be sufficient to cover all costs above the rails, as well as trackage fees and an appropriate return for investors. Spencer also plans to have an incentive program for Amtrak and other host railroads to improve the performance of the proposed trains. “We leverage all the competitive advantages of trains,” he said.

At this writing, Amtrak and essentially all local rail transit in the nation stand in a state of uncertainty without historic precedent. Ridership has plummeted everywhere and is only recovering slowly. Amtrak is slashing service on its long-distance network, possibly sending those trains to their demise. That could also doom political and financial support for the NEC. It is too early to tell what will happen anywhere, because nobody knows what course the COVID-19 pandemic will take in the future, or even whether or not there will someday be a vaccine that can stop its proliferation.

In the meantime, new plans are surfacing for keeping the NEC and its branches going on private-sector funding, especially now that the public sector is on its knees. Spencer says he is ready to go with the AmeriStarRail plan if it gets the appropriate green signals, and time will tell. There is another privately funded plan to take over and operate the infrastructure that the USDOT currently owns through a new Infrastructure Management Organization (IMO). It was once called AIRNet-21 and has changed its name to RAILNet-21. We will explore how that plan would work in a future article.

David Peter Alan is Chair of the Lackawanna Coalition, an independent non-profit organization that advocates for better service on the Morris & Essex (M&E) and Montclair-Boonton rail lines operated by New Jersey Transit, and on connecting transportation. In New Jersey, Alan is a long-time member and/or board member of the NJ Transit Senior Citizens and Disabled Residents Transportation Advisory Committee and Essex County Transportation Advisory Board. Nationally, he belongs to the Rail Users’ Network (RUN). Admitted to the New Jersey and New York Bars in 1981, he is a member of the U.S. Supreme Court Bar and a Registered Patent Attorney specializing in intellectual property and business law. Alan holds a B.S. in Biology from Massachusetts Institute of Technology (1970); M.S. in Management Science (M.B.A.) from M.I.T. Sloan School of Management (1971); M.Phil. from Columbia University (1976); and a J.D. from Rutgers Law School (1981). The opinions expressed here are his own.