Amtrak’s Gulf Coast Service Will Impose Sizable Costs on Freight Railroads

Written by Michael F. Gorman

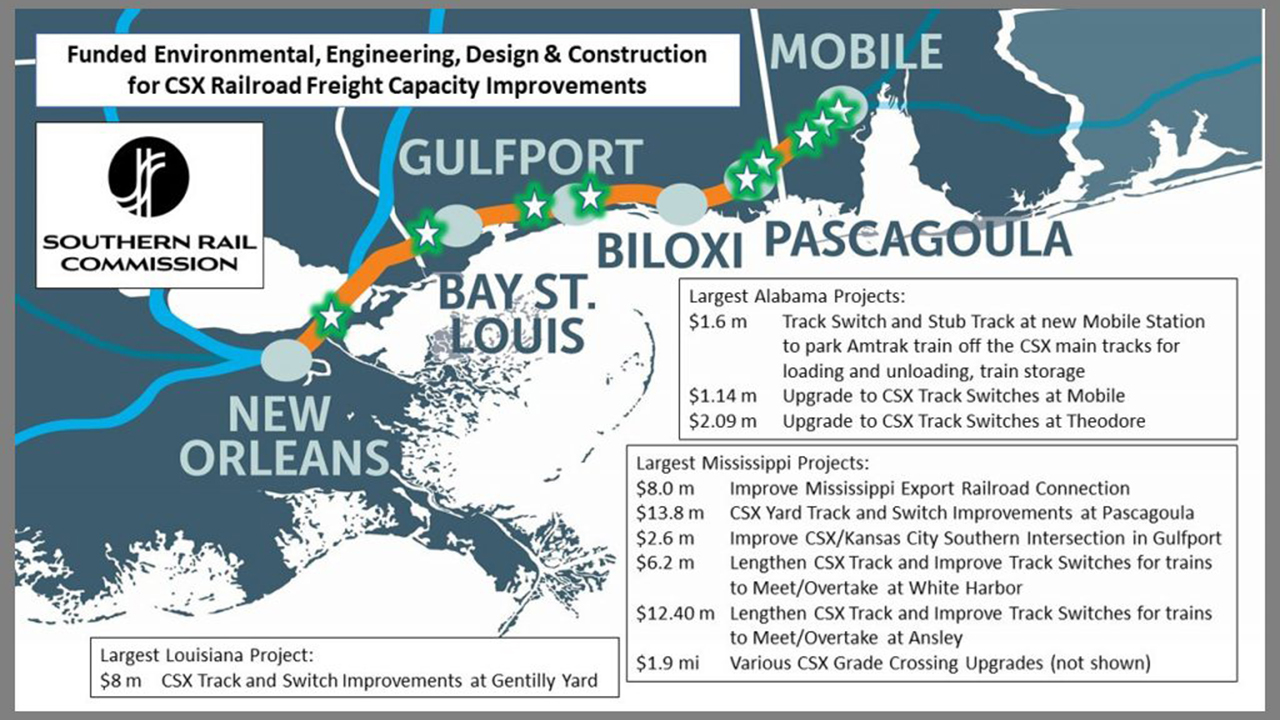

Southern Rail Commission illustration

Armed with $66 billion in federal funds from 2021’s Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, Amtrak has begun making plans to increase service across the country. Unfortunately, many of the markets it wants to expand into are lightly populated and evince little demand for passenger rail. However, this reality apparently does little to deter Amtrak from its growth mission, even when the opportunity costs of expansion are significant.

For instance, the company recently announced its intent to re-introduce service along the Gulf Coast of Louisiana, Mississippi, and Alabama. The proposed line would run from New Orleans to Mobile Alabama, with stops along the way. Amtrak’s blithe dismissal of the reality that passenger rail will impose costs on the freight railroads whose networks it will run on is highly questionable.

Prior to Hurricane Katrina, Amtrak ran three trains per week, but the storm caused it to be discontinued. The route—like nearly all Amtrak routes outside the Northeast Corridor—traversed tracks operated by freight rail companies, in this case, CSX and Norfolk Southern. Since Katrina, freight railroads have rebuilt their tracks at their own expense, with no federal and state subsidies.

U.S. freight railroads operate under capacity constraints: Railroads need to maintain a wide amount of space between trains for safety, limiting how much a rail network can carry. Resuming an expanded Gulf Coast passenger service will reduce the effective capacity of these rail networks.

Railroads spend massive dollars and manpower trying to get the most out of their tightly constrained networks. Despite increased train lengths, sophisticated algorithms for scheduling and dispatching trains, and billions of dollars in new tracks, the rail network is heavily congested. However, Amtrak tends to dispute this reality—both with the planned Gulf Coast service and elsewhere.

Amtrak’s current proposal for the Gulf Coast calls for two roundtrip trains per day, or 28 total trains each week, which constitutes nearly a ten-fold increase in rail service from pre-Katrina days. CSX and NS operate more than 10 through freight trains per day, plus a number of local trains, on these tracks.

Amtrak does not need to negotiate with the freight railroads to access these tracks; the Surface Transportation Board can simply mandate that freight rail give priority to Amtrak. Its growth plans give no heed to the havoc its expansion will cause to freight railroads. In fact, Amtrak claims that its operations will have no impact on freight rail traffic.

Such an assertion is demonstrably false. When an Amtrak train enters any freight rail network, freight trains must pull onto a siding to give the faster passenger trains priority.* This mandate wreaks havoc with scheduling, and it reduces the capacity of any rail network to transport goods.

With stops at ten locations in the route—including such metropolises as Pascagoula (population 21,732) and Bay St Louis (population 13,530) Mississippi—the Gulf Coast service will cause exceptional problems for the freight rail networks that have to adjust trains to the speeding—and then stopping—passenger trains. Further, Amtrak expects the Port of Alabama to alter schedules to accommodate Amtrak’s desired schedule.

Alabama Governor Kay Ivey and officials with the Port of Alabama have raised concerns about the desirability of such a service, citing the negative impact on Alabama’s economy.

While the hamlets that will have a stop may have more tourists, these gains will be far outweighed by the reduction in economic activity by the reduced capacity of the trains, which will mean the state’s ports will become less productive, increasing the costs of businesses in the state that rely on it.

Amtrak admits that the service will not have any impact on the number of cars on the road; and it claims that the service will boost tourism in the region. However, Amtrak projects that each train would carry only 20 riders, with a loss of over $300 per rider in perpetuity—funded by the US taxpayer at approximately $10 million per year. Twenty riders could be easily done via a bus. Amtrak already loses more than $1 billion a year before it even considers expanding service to smaller communities across the country, which are bound to be even less profitable.

Providing high-frequency train service to such a small population is a wasteful subsidy that will impose sizable costs on the freight rail industry, the Alabama economy, and U.S. taxpayers.

Michael Gorman is the Niehaus Endowed Chair in Operations and Analytics at the University of Dayton.

*Editor’s Note: The requirement that freight trains be “put in the hole” for Amtrak trains to clear may be what the statute that created Amtrak in 1971 dictates, but it is not always followed. Case in point: I recently rode the Capitol Limited from Chicago to Pittsburgh. My train, which left Union Station on time, was held in a siding for 80 minutes on the NS approaching South Bend, Ind., for three freight trains to clear. I made my connection to the eastbound Pennsylvanian with only minutes to spare. Stay tuned for a writeup on my March 2022 round trip between Newark and Chicago. — William C. Vantuono