Part 9: Can Texas Central Go Forward?

Written by David Peter Alan, Contributing Editor

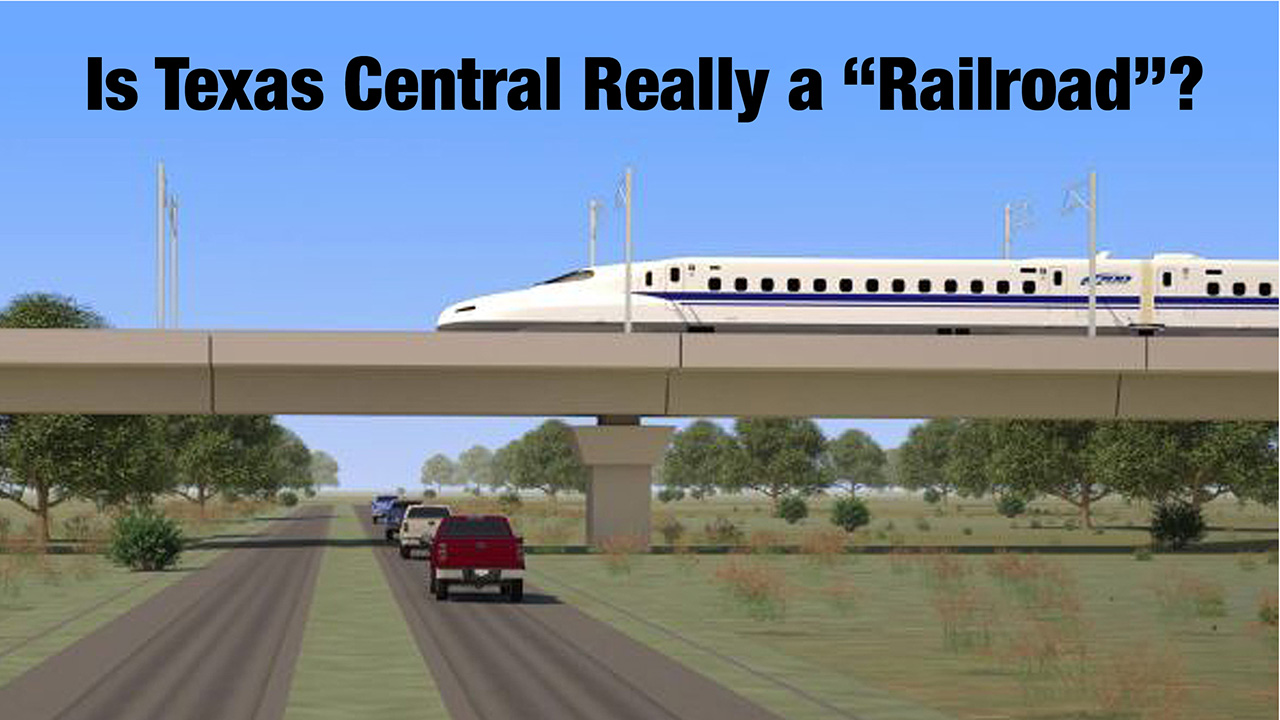

One month prior to this writing, it appeared that the proposed Texas Central high-speed rail line between downtown Dallas and a corner of Houston was about to suffer a fatal blow from the Texas Supreme Court. Texas politics favored such a result and, if that weren’t enough, its leader, Carlos F. Aguilar had quit.

We reported Aguilar’s departure on June 15, just nine days before the Court surprisingly decided that Texas Central was “an interurban electric railway” that had the authority to use private property by eminent domain. Peter LeCody, President of the Texas Rail Advocates, called the decision a “miracle,” and it certainly appeared that way. Yet, Texas Central still has a long way to go before its trains will be able to whisk passengers between Dallas and the Houston area in 90 minutes. In this commentary, we will examine where Texas Central and the idea behind it might go from here.

Plano, Tex., is a town north of Dallas. It has a historic-looking downtown area, reminiscent of 1915, the sort of town that is often called a “streetcar suburb” because of the way it developed. A term that contemporary transit managers and planners use to describe such places is “transit-oriented development” (TOD). Plano is the home to the Interurban Railway Museum, which commemorates the Texas Electric Railway and its line that brought riders to the town from Dallas until its demise in 1948. It also extended as far north as Denison and as far south as Waco. The museum is housed in the old interurban’s station in town, and original Car 360 stands outside on static display. According to the Court, such a line is at least the spiritual ancestor of Texas Central. In a way, perhaps the link between them is DART’s Red Line, which uses electric power to run light rail between Dallas and Plano today.

A Narrow Decision From the Court

The ruling from the Court only has mandatory authority within the borders of Texas, but opinions from a state’s highest court are often persuasive for judges deciding cases in other jurisdictions when there is no in-state case that is directly on point. The Texas Court’s holding might be an exception to that rule, though. Instead of having broad persuasive application, it might be limited to its facts.

Chief Justice Nathan L. Hecht argued that Texas Central was a “railroad” within the meaning of the state’s eminent-domain statute. From a railroad point of view, his argument makes sense. All railroads began as proposals and had to be constructed before they could operate trains. A holding to the contrary would have stopped any proposed railroad in its unbuilt tracks. Yet Hecht was only able to convince two other members of the Court to go along with his argument, when he needed four to constitute a majority. So Texas Central has eminent-domain rights as an interurban, even though the Court did not go so far as to consider it a “railroad,” notwithstanding the FRA having established separate rules for it in 49 C.F.R. Part 299. To put in mildly, the reasoning of the majority is not the sort of argument that judges in other states would be likely to consider persuasive on the issue of whether a proposed railroad has eminent-domain power to build the infrastructure that it will eventually need.

Could the U.S. Supreme Court Reverse the Texas Decision?

At this point, all Texas landowner James Fredrick Miles can do is petition the the Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) to review the decision of the Texas Court. By the legal reasoning in effect until two months ago, it would have appeared highly unlikely that such a petition would have gotten anywhere. The highest court of a state is the final arbiter of the laws of that state, and the case had never been filed in federal court, although the connection with Amtrak and the rules that the FRA had promulgated probably would have allowed a federal court to take the case. Even if the Court should wish to announce a ringing declaration of the supremacy of private-property rights and overrule Kelo v. City of New London, 545 U.S. 469 (2005) (which allowed eminent domain authority to be used for economic development), the holding in Miles appears very narrow, apparently limited to its facts, and those facts were different from those in Kelo.

Still, SCOTUS has recently turned to a strong policy of judicial activism, striking down federal policies and strongly endorsing states’ rights. There are now “pro-choice” states and anti-abortion states, while federal administrative agencies have lost much of their former authority over subjects like climate change, which the Environmental Protection Agency no longer has. On July 5, Frank Wilner commented here that the Court could have gone further to dismantle administrative authority at the moment, but also noted the Court’s recent activism. His observations make sense. The attack by the Court on administrative agencies is just beginning, and there could be many similar opinions in the future. The Court is now espousing jurisprudential theories not seen for 85 years, and which few of us who practice law today ever expected to return.

For now, at least, Texas Central can move forward, with existing electric railroad technology, anyway.

What About New Technology?

Trolley poles, pantographs and third rails are all devices used to collect electric power for the traction motors that propel a train, streetcar or historic interurban car forward. It is true that a modern high-speed train collects power from a wire in a similar manner, so the Texas Court’s decision managed to avoid flunking the “nonsense test.” That will be enough to allow Texas Central to survive for now, if it can. But what about new technologies that are currently under development?

Battery-powered trains are now being tested, and while it appears unlikely that batteries will be utilized to power passenger trains in the near future, improvements in battery technology could herald such use someday. There have also been experiments in Europe with hydrogen fuel cells to power trains. There are plans to use such an arrangement to run trains in San Bernardino County, Calif., within the next two years. Could these methods be used to power trains on an “electric interurban railway”? If they provide “electricity” to a motor that propels the train, those technologies would probably fill the bill. A new technology that directly runs a rail vehicle without going through a stage where mechanical energy is converted to electricity that would activate a traction motor would probably not qualify. This is another reason why the Court’s decision would be limited to its facts.

Going Forward From Here

I checked the Texas Central website, and it appears frozen in time, at a point 22 months ago. The most recent post was written in September 2020, and it was optimistic. There was no mention of James Frederick Miles and his action against Texas Central, not to mention Texas Central’s ultimate victory in court.

If Texas Central is going to meet its challenge to build a railroad and operate it, it will need to attract investors who can and would take the risk of betting now that the company will be able to build a railroad and then operate it later. That’s going to be a tough sell, but it would have been like that even if Miles had never filed his action in court. To make matters worse, the lack of an up-to-date website would give anybody, including potential investors, the impression that Texas Central is not a “going concern,” a situation hardly conducive to making a risky investment.

As I recently reported, Texas Central has its well-wishers: local officials like Houston Mayor Sylvester Turner, construction companies like Webuild, and advocates from around the nation who will support any new line that would add to the country’s passenger rail network. That includes the Texas Rail Advocates, who are on the front line in the Lone Star State, but it’s the investors with the money to risk who will decide whether Texas Central becomes a genuine “railroad” that actually operates trains.

Did Aguilar Give Up Too Soon?

Perhaps the most ironic event in the Texas Central saga so far is that CEO Carlos F. Aguilar threw in the towel a mere twelve days before the Court rendered the decision that has given the company a chance to attain its long-held goal. He used his LinkedIn page, rather than the Texas Central website, to announce his departure. Could Aguilar make the decision to come back to Texas Central, now that it got a signal from the Court to proceed, albeit an apparently limited one? Would future investors want him back, since he gave up less than two weeks before the Court delivered its decision? Will whoever is left at Texas Central prefer somebody else, not previously associated with it during the litigation? I can’t offer an answer any of these questions yet, but time will tell.

In his report on the Texas Rail Advocates’ website, LeCody quoted Texas Central “spokesperson” Katie Barnes saying that efforts will continue. Barnes is a lawyer practicing in Houston, according to the Texas Bar website, which also lists Texas Central as her professional affiliation. Her profile on LinkedIn describes her as “Director of Right-of-Way” for Texas Central, although SCOTXblog does not list her as one of the attorneys for Texas Central who appeared on the case.

If Barnes has been working on the “in-house” side of Texas Central, rather than the litigation, her status makes sense. There have been cases where a business entity is not rich in assets, although it still has a cause of action that the business hopes will lead to a victory in court and an improvement in its fortunes. Texas Central has that, and in this sort of situation, in-house counsel has to keep the organization going during the ensuing effort to rebuild. LeCody commented that he expects the rebuilding effort to take 12 to 18 months. He may be right. He may be unduly optimistic, instead.

Looking Toward the Future

Texas Central has won in court, at least as far as Texas is concerned. That means the remaining management can make an effort to rebuild the company, attract investors and get back on track—which means, quite literally, building that track first. They can get the land and the easements they need, which gives Texas Central a chance to live.

It looks like a long shot for them, but winning at the Texas Supreme Court looked like a much-longer shot, essentially impossible.

Advocate Peter LeCody characterized the Court’s decision as a “miracle,” and Texas Central may need another. Still, long shots have come through: The future United States winning its War for Independence against the mighty British forces was one of the most unlikely in history, until it happened. Ukraine might yet win the war that Vladimir Putin’s Russia visited upon it, too. I don’t know, as things stand now, but Texas Central might end up being “The Big, Fast Train that Could.”

David Peter Alan is one of America’s most experienced transit users and advocates, having ridden every rail transit line in the U.S., and most Canadian systems. He has also ridden the entire Amtrak network and most of the routes on VIA Rail. His advocacy on the national scene focuses on the Rail Users’ Network (RUN), where he has been a Board member since 2005. Locally in New Jersey, he served as Chair of the Lackawanna Coalition for 21 years, and remains a member. He is also a member of NJ Transit’s Senior Citizens and Disabled Residents Transportation Advisory Committee (SCDRTAC). When not writing or traveling, he practices law in the fields of Intellectual Property (Patents, Trademarks and Copyright) and business law. The opinions expressed here are his own.