Part 3 of 5: The Court Pivots and Accepts the Case

Written by David Peter Alan, Contributing Editor

For a short time, it looked like the end of the line for James Frederick Miles and his supporters. Miles is the landowner from a rural county between Dallas and Houston who had fought fiercely against the proposed Texas Central high-speed rail (HSR) line between Dallas and a point near Houston. He had defeated the Texas Central Railroad & Infrastructure, Inc. (TCRI) and Integrated Texas Logistics, Inc. (ITL, known collectively as “Texas Central”) in a local court. When Texas Central appealed, the appellate court reversed the lower court’s verdict and ruled in favor of Texas Central. Then Miles petitioned the Texas Supreme Court for review, and the Court denied his petition on June 18, 2021.

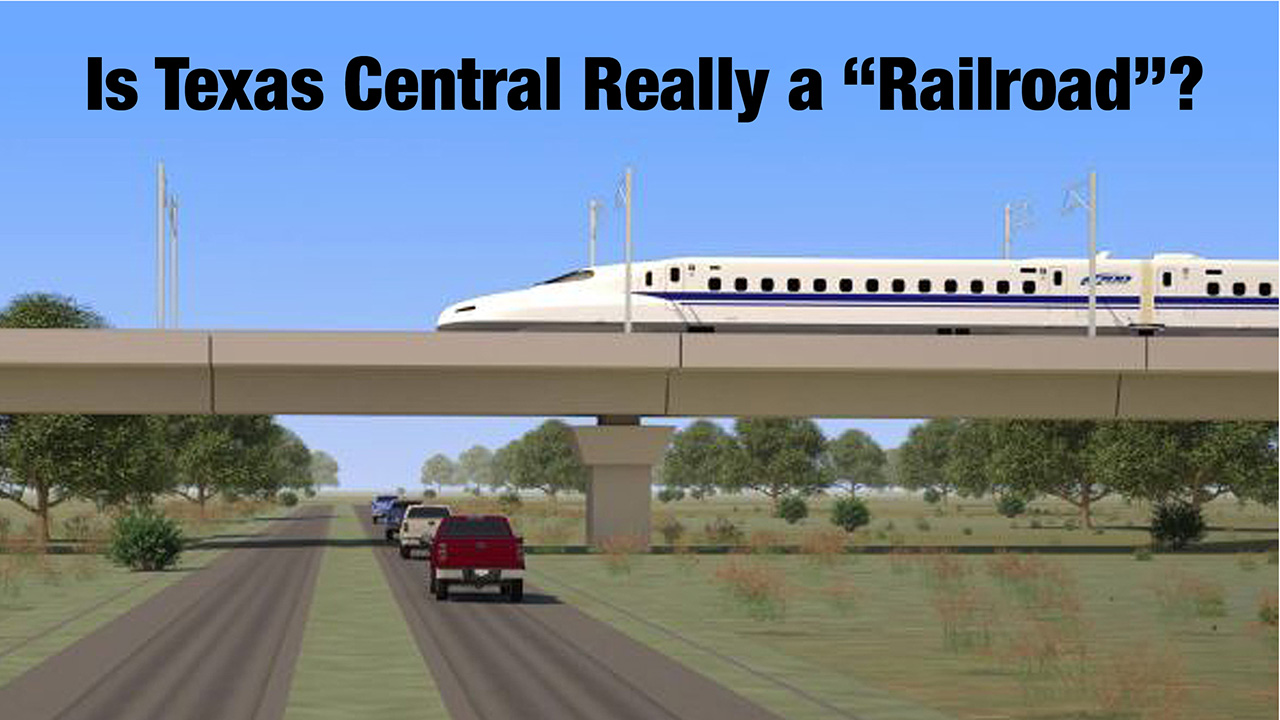

Texas Central wanted to conduct a survey on Miles’s land to use some of it for the right-of-way of its proposed line. He objected and refused permission. The original issue in the case was whether Texas Central was actually “operating a railroad” or was an “electric interurban railway company”; either status conferring authority to condemn land (or at least an easement across it) by eminent domain. There were other issues, too; particularly whether or not Texas Central had a “reasonable probability” of completing the project and placing the new line into service. As we reported in the first two articles in this series, there were other issues, and many non-parties who filed amicus (“friend of the court”) briefs supporting Miles’s side of the controversy, at least as far as that point in the proceedings.

High courts, whether the U.S. Supreme Court or the highest court of a state (usually, but not always, called the State Supreme Court) have absolute discretion when deciding whether or not to accept a case for review when a petitioner requests it. Such petitions, including Miles’s, allege that the lower court decided the case incorrectly and ask the Court to accept the case and correct the errors by reversing the decision. Miles garnered support from diverse places, including ranchers’ associations, the governments of the counties along the proposed line, and SNCF America, the U.S.-based subsidiary of the French national railroad SNCF. It appeared that the effort had been unsuccessful, because the Court said no, and courts rarely change their minds after they decide not to review a case.

The Battle Resumes

Miles’s case was different, though. Seven days later, on June 25, the Court accepted Miles’s request for rehearing and set July 30 as the deadline for Miles to file his motion in support of that request. His attorneys filed it on July 29. Thus began a new chapter in a saga that could result in the end of new passenger rail starts in Texas, and perhaps in much of the rest of the country.

Miles immediately went on the attack in a brief supporting his motion for a rehearing (available at https://search.txcourts.gov/SearchMedia.aspx?MediaVersionID=8209c3d7-3684-436b-b7f5-0232038e828c&coa=cossup&DT=REHEARING&MediaID=757f5a11-91f1-4c50-bfc8-1213780aa546). He pushed hard, with allegations that were worded more strongly than in the briefs he filed in the previous proceedings before the Court. For example, Miles alleged: “A group of wealthy … businessmen decided they would try to take the land from their fellow Texans whether the landowners liked it or not. They formed Respondent Texas Central Railroad & Infrastructure, Inc. (‘TCRI’) and falsely claimed it was operating a railroad in Texas and that it had the power to exercise eminent domain. Armed with nothing more than these false claims, TCRI began threatening landowners in an effort to survey their private property and sued those (like Petitioner Miles) who refused” (at 1).

The proverbial gloves had come off. After alleging again that Texas Central was not “operating a railroad,” Miles again attacked the lower court’s holding that it was an “electric interurban railway company” by saying, “Once again, this claim was false. TCRI has never had any intention of constructing or operating a mode of transportation that has been extinct in Texas since 1948—namely, one of these,” showing photographs of historic cars from the long-defunct Texas Electric Railway and Denison & Sherman Railway (at 3). Miles made other allegations, including false claims and bullying tactics, and repeated the technical arguments about grammar from his former briefs.

Miles’s arguments were: 1) In Texas, private property rights are supposed to mean something. 2) In Texas, if there is any doubt about eminent domain authority, courts must rule in favor of the landowner. 3) As it stands, anybody with $300 and a pen can obtain eminent domain authority in Texas immediately upon incorporation. 4) With respect to high-speed rail, the Legislature had made its intentions clear. 5) Miles’s Petition for Review presents an important question of state law that should be resolved by this Court. It is customary to argue the fifth point as a basis for persuading the Court to exercise its jurisdiction to accept the case for review, especially in the matter at issue, when the Court had recently declined to do so.

The character of Miles’s brief in this round appeared different from those filed by his attorneys in the two previous rounds. The language was more combative, even hyperbolic, and the brief had eye-catching features like photographs, a full-color chart, and boxes with words highlighted in yellow. At that time, it remained to be seen whether or not this change of litigation style would affect other parties.

Miles’s Supporters Chime In

Within four days, the amicus (“Friend of the Court”) letters started coming in, supporting Miles’s request. They came from KSA Industries (a real estate, agricultural and financial company), four property owners claiming that the railroad would damage them, the Texas Farm Bureau (appearing again), a group of six state legislators from the area, a seventh legislator who filed a separate letter, a cattle raisers’ association, the Texas Department of Agriculture (by the Commissioner), Congressman Jake Ellzey, and famed anti-passenger-rail activist Randal O’Toole. All twelve letters supporting Miles’s position were filed with the Court before Texas Central even filed its own brief.

Texas Central Has its Turn

Amid this growing opposition, Texas Central (as TCRI and ITL) filed its response (found at https://search.txcourts.gov/SearchMedia.aspx?MediaVersionID=82078276-d612-4bdb-a00c-9b18a53c3bf6&coa=cossup&DT=REHEARING&MediaID=4e39cb17-bfc9-46d9-8cba-b4208bf4e9d9). Texas Central’s brief stood in contrast to Miles’s. It looked like a conventional brief, without the eye-catching features or the strongly combative language that characterized Miles’s. It began: “This Court’s decision to deny Miles’s petition for review was correct and rehearing should not be granted. Miles and his amici have offered no new arguments for why this Court should reject the Court of Appeals’ conclusion that Texas Central has survey and eminent-domain authority to build the high-speed train between Dallas and Houston … Miles’s Motion for Rehearing and his amici still make no valid arguments—and make no new arguments at all—for this Court reaching any different result” (at 1).

Texas Central argued that the high-speed train will bring great economic benefits to Texas, saying, “Miles and his amicipoint to the costs of the high-speed train while ignoring its benefits” (at 3) and listing organizations that support the project. Other arguments claimed environmental benefits, improved public safety, and “The high-speed train will benefit every segment of society” (at 6).

Regarding the holding of the lower court, Texas Central argued: “Miles’s motion for rehearing contains no legitimate or new arguments for rejecting even one of Texas Central’s three bases for survey and eminent domain authority under the Transportation Code” (at 6), arguing that Texas Central was operating a railroad, would be operating a railroad in the future, or was an electric interurban railway company, any of which would confer authority to exercise eminent domain to acquire land or land use under the statute around which the case revolves, §81.002(2) of the Texas Transportation Code. Texas Central attacked Miles’s argument that an entity must be operating trains on tracks to be qualify, claiming that such a requirement would create an “unconstitutional monopoly” for a company that already had such infrastructure and could keep competitors out (at 8-9).

Most of Texas Central’s brief contained classic arguments about statutory construction, supporting the reasoning by the appellate court, which had reversed the trial court’s finding for Miles. The brief concluded: “Texas Central prays that this Court deny Miles’s motion for rehearing. Miles’s petition for review was properly denied by the Court because Miles provides no legitimate (or even reasonable) argument as to why Texas Central does not satisfy the Texas Transpiration Code’s definitions for one having survey and eminent domain authority to build a high-speed train in Texas” (at 21).

Texas Central Gathers its Own Supporters

Seven more amicus letters were filed from Sept. 20 through Oct. 6. The North Texas Commission, the City of Houston, Dallas County, the City of Dallas (through its mayor), the Metropolitan Transit Authority of Harris County (Houston Metro), three Harris County commissioners, and Sen. Royce West (whose district is located in Dallas) all supported Texas Central’s position and urged that the Court affirm the holding from the court below. Texas Rail Advocates attempted to submit a letter, but it was struck. That organization would later join in a brief with two business groups.

On Oct. 15, the Court withdrew the denial order of June 18 and granted Miles’s Petition for review.

There were six more amicus letters filed during the rest of 2021. Five of them supported Texas Central: the City of Fort Worth, the Texas Association of Business, the Regional Black Contractors Association, the Greater Houston Partnership, and the Texas Aggregates and Concrete Association. That made twelve supporters for the project; making the tally even with the number of letters urging the Court to reverse the decision. On Jan. 6, 2022, the American Council of Engineering Companies of Texas also filed a letter supporting the project.

The State Throws Support to Miles

The seminal development, perhaps in the sense of determining the outcome of the case, came on Dec. 17. It was a brief filed by the Solicitor General’s office on behalf of the State of Texas, siding with Miles and urging the Court to reverse the decision. The Court had invited the State to participate in the case on Oct. 15. The State also participated in oral arguments on Jan. 11, 2022 (which sounds like the status of a full-fledged intervenor, rather than merely an amicus).

The State’s brief (found at https://search.txcourts.gov/SearchMedia.aspx?MediaVersionID=8a15c308-7590-46c5-b106-ae1f8a7438b8&coa=cossup&DT=BRIEFS&MediaID=27d92175-ad98-4e38-9c4c-e6643d1befaa) began with an irrelevant sentence, and then stated its position: “The State takes no position on the wisdom or utility of building a high-speed train between Dallas and Houston. But private actors who seek to seize private property using eminent-domain powers must strictly comply with statutory and constitutional conditions governing the use of such powers. Respondents have not.” The argument on the substance of the statutory construction issue of whether Texas Central was “operating a railroad” or was an “electric interurban railway company” looked much like those propounded by Miles’s attorneys: “Respondents are not operating anything resembling a railroad. That they might possibly do so someday is not enough. The second category refers to small, localized electric railways that are designed to transport passengers between a city and its surrounding areas. Respondents’ proposed multi-billion-dollar, cross-state high-speed train does not fit the bill.”

Then the state argued that Texas Central cannot demonstrate a “reasonable probability” of being able to operate a railroad, again agreeing with Miles. The brief noted that a statute enacted in 2017 “amends the Transportation Code to prohibit the legislature from appropriating money to pay for certain costs associated with high-speed rail operated by a private entity and to prohibit a state agency from accepting or using state money to pay for such a cost” (at 6-7; citation omitted). In other words, any HSR project could not be funded with any State money.

The State propounded lengthy arguments about how Texas Central was not “operating a railroad” (at 15-30) and was not an “electric interurban railway company” (at 30-34). An example of the former: “The ordinary meaning of ‘operating’ and ‘railroad’ is running passenger or freight trains on fixed tracks” (at 18). An example of the latter: “An interurban is a small, localized electric railway” (at 31). The grammatical arguments were included, too (at 20-22). The argument then became that Texas Central does not have authority to exercise eminent domain (at 34-44).

After reviewing similar briefs filed during earlier stages of the case, a review of the State’s case does not reveal much that had not already been said by Miles and the other amici who supported him. Perhaps the most noteworthy feature of the State’s brief indicates the lengths to which the boundless legal resources of the State could be directed toward finding obscure provisions that do not appear to have any material effect on the outcome of the case. The most notable example concerned a statutory aspect of the fare structure for interurban and street railways: “What’s more, the Respondents have no convincing answer for section 131.103, which requires interurbans that join with street railway companies to sell half-price tickets ‘in lots of 20’ to students ‘younger than 18 years of age who attend … school in a grade not higher than the highest grade of the public high schools located in or adjacent to the municipality in which the railway is located.’ Tex. Transp. Code §131.103(a)-(b). This grade-school student-commuter provision is inconsistent with the cross-state high-speed rail project the Respondents intend to operate” (at 33).

There can be no doubt that a brief as thorough as the one filed by the State requires a great deal of time and effort from the attorneys and support staff involved in producing it. All other documents filed by the many amici in the case, whichever side they supported, bore a statement indicating that the person or entity filing the document paid for its preparation. That was not the case for the State’s brief, as indicated at the outset: “This brief responds to the Court’s letter of October 15, 2021 inviting the Solicitor General to express the views of the State of Texas. No fee has been or will be paid for the preparation of this brief” (at ix).

Therefore, it was the taxpayers of Texas who paid for the State to restate arguments made by a private party and his supporters. It also appears curious that the Court would refuse to review the case and later specifically invite the State to become involved with the matter, when it had previously been a dispute between private parties who had briefed every issue thoroughly. The alleged letter from the Court was not included in the case record, as found on the Texas Courts website, https://search.txcourts.gov/Case.aspx?cn=20-0393&coa=cossup. All documents cited or quoted in this series, as well as the chronological history of the case, were found at that source.

Texas Central’s Last Response

Texas Central filed its response on Jan. 3, eight days before oral argument was to take place (found at https://search.txcourts.gov/SearchMedia.aspx?MediaVersionID=ccc30669-a181-4dc7-9ac7-1b9673ab37f8&coa=cossup&DT=BRIEFS&MediaID=95152579-fce1-4c52-8f11-48f2cfb6d14a). One change was that the brief referred to the opposition as “SG/Miles,” acknowledging that the State had become an official adversary (“SG” stands for “Solicitor General,” the official charged with arguing cases in court on behalf of the State). The brief began: “The Solicitor General (“SG”) puts forward the same baseless positions asserted by Petitioner Miles. Those positions have no more merit merely because they are now advocated by the State’s Attorney General or his lead counsel” (at 1) but, like the opposition, Texas Central mainly restated the arguments it had made before: that “The SG/Miles’ interpretation of the Texas Transportation Code is contrary to the plain statutory text, the Texas Constitution, and the Court’s precedents” (Id), “The SG/Miles ignore the huge benefits that the high-speed train will bring to Texas” (at 3), and that reliance by SG/Miles on a specific case was misplaced.

In addition, Texas Central argued: “The SG/Miles ask the Court to alter the balance of competing interests that the Legislature struck in the Transportation Code” (at 4), an argument that was developed in more detail than in previous filings: “When the SG/Miles ask the Court to engraft, onto the Transportation Code provisions, some sort of reasonable-probability-of-completion test, they are asking the Court to upset the balance of interests already struck by the Legislature. But the Court does not sit to rewrite statutes” (at 5, citation omitted). Texas Central again argued that it had the statutory right of eminent domain, and that the appellate court’s construction of the statute was reasonable and correct.

The grammatical arguments were still there, but there were policy-oriented arguments, too. An example: “The Transportation Code regulates activities engaged in by a railroad company before it has trains on tracks” (at 22-23; related arguments presented at 23-32). The brief refuted arguments presented by the State for the first time, for example, saying that the statute pertaining to reduced fares for student tickets applied to street railways and not to interurban lines (at 36) and made broad policy arguments, including: “The Court should decline the SG/Miles’ invitation to alter the balance that the Legislature has already struck between the public need for infrastructure and the interest of property owners” (at 40). That argument included these words: “The SG/Miles effectively ask the Court to alter the balance that the Legislature has already struck—between the needs of the public and the interests of private landowners—when the Legislature gave survey and eminent-domain authority to a private entity operating a railroad business/enterprise or building/operating an interurban electric railway. The Court does not sit to rewrite statutes or to re-strike the balance of interests made by the Legislature” (at 41). There were other arguments, but one sounded a particularly cautionary note: “The SG/Miles’ proposed reasonable-probability-of-completion test would turn condemnation law on its head and chill public infrastructure projects” (at 43).

Texas Central Gets Last-Minute Support

There were two more amicus briefs filed on Jan. 10, the day before oral argument. Both supported Texas Central and urged the Court to affirm the judgment of the lower court. Together, they represented five organizations. The one filed earlier was submitted on behalf of the Greater Houston Partnership, which promotes business in the Houston area, and the North Texas Commission, a similar organization in the Dallas area (found at https://search.txcourts.gov/SearchMedia.aspx?MediaVersionID=1700963a-d578-418a-a15e-514021d9c916&coa=cossup&DT=BRIEFS&MediaID=cfc4e29b-abc6-4d2c-80f3-89d79af09c92). They argued that the other side would “create new standards hostile to innovation that not only are skewed heavily against high-speed rail, but also against development of crucial infrastructure in other realms beyond transportation” (at v). After attacking the contention by Miles and the State that Texas Central lacked eminent-domain authority, they argued: “A common and alarming theme runs through these erroneous contentions: The tools necessary for infrastructure development in Texas are available only to entrenched entities that already have physical assets in place, and then only for outdated technologies” and went on to say that implementation of that policy would hinder efforts in Texas to attract business into the state (at 2).

The brief was the first to downplay the grammatical arguments, saying: “This Court need not get into the weeds on tenses because the premise underlying the State’s argument is erroneous. It is erroneous because, read in context and as a whole, the Transportation Code’s unambiguous language confirms that Texas Central Railroad is, today, engaged in railroad operations” (at 4). The Houston brief also questioned the “reasonable probability” standard requested by Miles and the Solicitor General: “The inability to articulate a coherent and consistent formulation of the supposed ‘statutory requirements’ that must be established to a ‘reasonable probability’ is a red flag. So too is the effort to characterize amorphous concepts such as political and financial feasibility—which do not even arguably appear in any of the statutes at issue—as ‘statutory requirements’ for a ‘reasonable probability’” (at 12), and also questioned “how this scheme would work in the context of a years-long project to build a highway crossing multiple counties” (at 13).

The latter-filed brief, and the last before oral argument, was submitted by the Dallas Regional Chamber of Commerce and the Dallas Citizens’ Council, an organization composed of business leaders in the city (found at https://search.txcourts.gov/SearchMedia.aspx?MediaVersionID=6516b086-a915-4b83-bf76-4375de80928a&coa=cossup&DT=BRIEFS&MediaID=e38cf4e6-3872-47a8-aa80-00f5f1377d58).

Texas Rail Advocates, the statewide organization that advocates for improved local and intercity rail service in Texas, joined the two Dallas business groups on the brief (as described at 2). They argued that Texas Central has eminent-domain authority, based on both the “operating a railroad” and the “interurban” standards, and went on to say that, even under the “reasonable probability” standard that they attacked as not based in statute or the Texas Constitution, Texas Central would meet it, anyway (at 14), and that Miles “lacks faith in Texas Central’s ability to succeed. But that does not entitle him to a veto over an infrastructure project that is in progress and will undeniably be dedicated to public use once completed” (at 16). The brief argued: “At this point, Petitioner can only speculate that the company’s failure will cause him any legally cognizable injury” (at 17) but, even if the project were to fail, he would have sufficient legal recourse to recover actual losses.

Overall, the last two briefs were filed from a “business” perspective, and both argued that if the Court were to reverse the lower court’s decision, it would hinder business development in Texas, despite that being a major goal of the State. It could appear that the State is now arguing against its longstanding policy.

The same day that Texas Central filed its response, the Court granted the State’s unopposed motion to participate in oral argument, giving it five minutes from the time that Miles originally had, so Miles had 15 minutes, while Texas Central would still have 20 minutes. All other recent case documents concerned preparations for oral argument, which was scheduled for Tuesday, Jan. 11. Information from the court site was current as of Monday, Janu. 10.

The briefs have been filed, the issues have been defined, oral argument has taken place, and now it’s all over but the waiting. Is there really any need to wait, though? When the Court delivers an opinion, we will review it and report about it. But the twists and turns of this particular case, along with the realities of Texas politics, make it unusual. The Court will soon decide the fate of the Texas Central project; that is what Miles requested when he brought his case in a local court back in 2016.

Beyond this project, though, the Court will also decide whether or not there will be any similar projects proposed in Texas in the foreseeable future. That is not the Court’s task, but it will almost certainly be the result. The eventual effect of the Court’s decision could also have national policy implications. We will examine those political realities and policy implications in the next article.