Part 2 of 5: More Opponents Line Up

Written by David Peter Alan, Contributing Editor

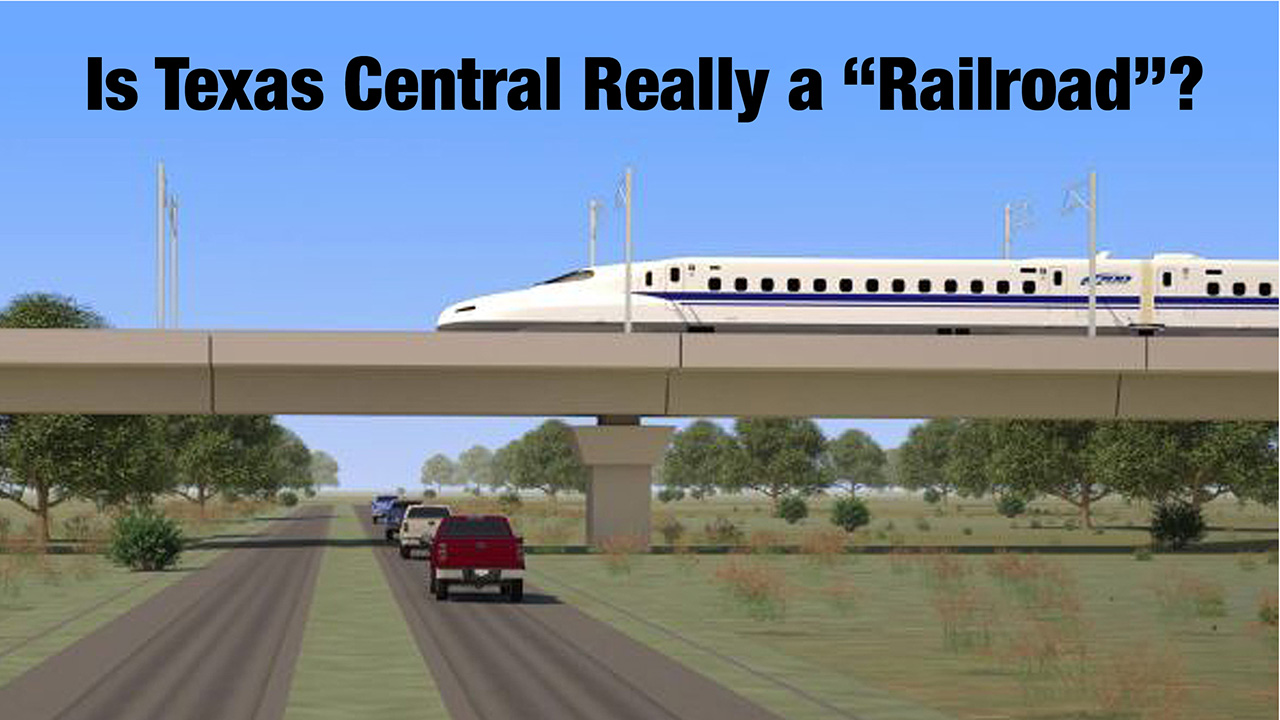

A landowner in rural Texas is locked in a legal battle with the companies that are planning to build the Texas Central high-speed rail (HSR) project, which would establish a line between downtown Dallas and the intersection of two highways northwest of Houston. Texas Central plans to offer a 90-minute trip time point-to-point, using Japanese Shikansen equipment.

James Frederick Miles, the landowner, objected to having a rail line running on his land, especially a high-speed line with all of its infrastructure. When the company want to survey his land, he refused to allow them to do so, claiming that they did not have the authority to make use of his land for the railroad by authority of eminent domain. He sued Texas Central Railroad & Infrastructure, Inc. (TCRI) and Integrated Texas Logistics, Inc. (ITL) (collectively “Texas Central”) to keep them from continuing.

As we reported in the previous article in this series, Miles won at the trial-court level in rural Leon County. The local judge found that, as a matter of law, Texas Central did not have the sort of authority to exercise eminent domain that was granted to railroad companies in Texas by statute. Texas Central appealed, and the three-judge appellate panel reversed, holding that TCRI and ITL were “operating a railroad” and were “electric interurban railroad companies” within the meaning of the statute.

A Petition to the High Court

Not willing to accept that reversal, Miles raised the stakes. He asked the Texas Supreme Court to review the case. A number of other entities submitted briefs supporting him, and those briefs raised a multitude of issues about the specific issues surrounding the case and about HSR generally. It appears that at least one party has briefed essentially every issue concerning HSR or building a new rail line generally, in this matter.

On July 18, 2020, Miles filed his petition to the Court for review (case 20-0303), represented by four different law firms (at https://search.txcourts.gov/SearchMedia.aspx?MediaVersionID=c7ae339d-cc92-4348-97c1-533c50136f45&coa=cossup&DT=BRIEFS&MediaID=0f3dbb03-ab93-48df-85f7-5534566e781a). His Statement of the Case began: “This is one of more than forty lawsuits arising out of Respondent Texas Central Railroad & Infrastructure, Inc.’s (TCRI) plans to build and operate a 240-mile high-speed rail line between Dallas and Houston. The controversy stems from TCRI’s claim that, despite being a private corporation, it possesses eminent domain authority, giving it the right to enter onto, and eventually condemn, landowners’ property—all without the landowners’ consent. (at viii).” Miles argued: “The Court should exercise jurisdiction to review this case because it presents critical issues of first impression arising at the intersection of Texas’s infrastructure needs, population growth, and private property rights” (at x), that “TCRI’s inexperience and undercapitalization raise alarms” (at 6), that TCRI and ITL are not a “railroad company” or “operating a railroad”; and that an entity that might operate a railroad in the future is not enough, arguing that the Court is not required to equate the future with the present (at 16-17). Miles used this grammatical argument: “‘Operating’ is not a ‘present’ tense verb that can be converted to ‘future’ tense. It is a present participle, referring to an ongoing ‘state of … action’: one that began in the past, continues into the present, and will continue into the future. A present participle cannot be collapsed into a simple ‘present’ tense. Nor can it be translated into a ‘future’ tense because there is no such thing as a future participle in the English language” (at 17).

Miles then argued that the Texas Central companies (TCRI and ITL) could not demonstrate a “reasonable probability” that they will ever be “operating” a railroad in the future. While not specifying what quantum of likelihood would comprise a “reasonable” probability, the petition argued that whatever preliminary work Texas Central had done fell far short of that standard: “No matter how much preparatory work Respondents have done and are doing toward their goal of building a railroad, that cannot serve as evidence of the likelihood of success in the future. That is especially so when Respondents have nothing tangible to show for the roughly $125 million they have spent, and have done nothing to bridge the enormous gap between the $450 million they have raised and the $30 billion they acknowledge they will need” (at 18) and continued: “The only conclusion to be drawn from the evidence is that Respondents’ venture is likely to end in failure, and Texas landowners will be left to deal with the fallout” (Id.), adding that, if the railroad were not built, Miles’s remedy of buying back the condemned land “will not undo the damage.”

Miles then argued that the appellate court below was wrong to consider Texas Central an “interurban electric railway company” and distinguished the proposed HSR line from the historic interurban lines from the past century. According to the argument, the statutory definition “indicates that the concept of an ‘interurban electric railway’ is a technical term. It is one that does not describe a specific mode of transportation – so as to encompass any train running on electricity between cities – but rather a specific kind of train: the single-car interurban electric railways that were an ‘outgrowth of the urban trolley car. These railways carried electricity as often as they carried passengers, which is why section 131.061 authorizes them to transmit electricity. They also resembled the single-car streetcars of the era and were meant to connect to streetcar systems, which is why section 131.015(a) provides interurban electric railways eminent domain authority to connect their tracks to streetcar systems. And these railways have all but disappeared today” (at 19-20, citing William D. Middleton, Goodbye to the Interurban, Or Is It Hello Again?, American Heritage, Apr. 1966, https://www.americanheritage.com/goodbye-interurban at 48). The document did not say how an interurban car “carried” electricity, which is a means of propulsion, or compare such a means with how it “carried” passengers.

Nonetheless, Miles’s citation of the Middleton article may actually support the opinion of the court below, more than refuting it. After describing the history of interurban lines, Middleton concluded his article with these words: “The big old electric car, dusting through the meadows with its air horn shrieking for the crossings, is only a museum piece. Yet something is coming back, something without the wicker and the inlaid woodwork, something a little too streamlined and shiny perhaps, but something to hearten those who loved the most open road of all, the rails of the interurban.” While the lawyers representing Miles argued strongly for the lack of a connection between the interurban lines of the past and the Texas Central project, the article they cited could also be construed as foreshadowing a connection between those interurbans and the sort of “streamlined and shiny” train that the Texas Central project proposes to bring to the Lone Star State, but was not otherwise foreseeable more than 55 years ago. It will be interesting to learn whether or not the Court discusses that issue in its opinion.

Texas Central Responds

The Response filed by TCRI and ITL (again, collectively “Texas Central) on August 28 (and found at https://search.txcourts.gov/SearchMedia.aspx?MediaVersionID=4ee3a937-3c31-4414-92a4-4ab85041f08e&coa=cossup&DT=BRIEFS&MediaID=dc11f1e5-2f7a-4d05-99ec-662ee29ad5d2), requested that the Court deny Miles’s petition for review. To introduce its brief, Texas Central claimed that “thousands commute between Dallas and Houston”; almost all by automobile. … “By enabling a 90-minute commute between Dallas and Houston, Texas Central’s highspeed train offers a compelling solution to mobility problems along the Dallas/Houston corridor” (at 1), that a broad coalition supports the project, and that it would produce numerous benefits, including creating “employment opportunities [for] minority and/or low-income populations” and it “will give those populations “an alternative mode of transportation from Dallas to Houston” (Id).

Texas Central claimed that it was “doing all things railroad companies do at this stage” (at 3) and listed its efforts up to the time the document was filed with the Court (at 3-5). Those activities included acquiring land, procuring rolling stock, negotiating with Amtrak for connectivity, technical consulting including with the Central Japan Railway Company, and engagement with the FRA, the STB, and other federal and state regulatory agencies. Texas Central also cited a report that Gov. Greg Abbott had gone to Nagoya to meet with officials from the Japanese railroad (at 5, n.5). Perhaps as a preview of the politics to come, Texas Central noted that Miles was a former Leon County Commissioner (at 6).

As expected, Texas Central argued that the court below had made the correct decisions on the issues. The Summary of the Argument included this paragraph: “There is no need for a new constitutional test by which prospective condemnors must prove the likelihood of completion of the public project. Statutory and common law already address that risk of non-completion of public projects. And Miles’s proposed new constitutional test would imperil ambitious public infrastructure projects in Texas – whether by a state entity or a private condemnor” (at 8). Texas Central continued: “If the Court were to require some specified degree of certainty that multi-billion dollar, decades-long public projects will succeed, then such a rule would apply to all ambitious public infrastructure projects in Texas” (at 10) and went on to list the activities that support its claim that the project is progressing (at 11).

For the rest of its brief, Texas Central defended the findings and holding of the court below: that Texas Central is a “railroad company” within the statutory meaning of that term: “The Transportation Code’s definition of ‘railroad company’ demonstrates that a ‘railroad’ is a business engaged in railroad activities – not physical trains on tracks” (at 12), that “Trains on tracks cannot be ‘incorporated’; only a business or enterprise can be ‘incorporated’” (at 13), and that “under the Transportation Code, a “railroad” is an enterprise in the railroad business, as opposed to physical trains on tracks” (Id). That includes “to use eminent-domain authority to build the very first track” (at 14; emphasis in original).

If the Court were to agree with Miles, Texas Central argued that such a result would restrict eminent-domain authority in other situations, as well, and would grant “an unconstitutional monopoly to companies that already have trains on tracks” (at 15-16). For example: “Miles would construe the Texas Transportation Code in a way that gives eminent-domain authority to a European company (that already has trains on tracks in Germany) to build a high-speed train between Dallas and Houston, but that would deny such eminent-domain authority to a new Texas company” (at 15).

In response to Miles’s grammatical arguments, Texas Central demonstrated that it could play that game, too, saying that the companies “will be operating a railroad” (at 16, emphasis in original) and that, as the court below ruled, present tense includes future tense. Regarding tense, Texas Central argued: “Miles wrongly denies that the word ‘operating’ has a future-tense form: ‘will be operating. After expanding on that theme, Texas Central concluded: “The Court of Appeals correctly rejected Miles’s invitation to ignore the Code Construction Act’s plain language” (Id), and that an “ordinary citizen … would recognize that words in the present tense include the future tense” (at 19).

Texas Central also defended the holding below on another issue: “The Court of Appeals correctly concluded that Texas Central is an ‘interurban electric railway company’ under the Transportation Code” (at 20), primarily through arguments related to statutory construction, saying: “Here, even if an ‘interurban electric railway’ originally encompassed slower-moving electric trolleys, the Transportation Code’s language is broad enough to include Texas Central’s high-speed train. Miles’s desire to write technological restrictions into the statute is no reason for this Court to grant review” (at 22).

Miles Replies to Texas Central’s Response

Attorneys for Miles filed a Reply on September 22 (which can be found at https://search.txcourts.gov/SearchMedia.aspx?MediaVersionID=e0257d72-d5dd-4346-a96a-42553a8a3976&coa=cossup&DT=BRIEFS&MediaID=db2bd4c8-6b2d-41ff-9e99-250d8f6871cd). Miles highlighted the importance of the case, listing an array of concerned non-parties, including a few amici who had already filed papers: “All these voices demonstrate the world-wide impact of Respondents’ project, touching everyone from high-tech, high-speed rail companies, to old-world ranchers, to thousands of Texas landowners. These people deserve to have this Court determine whether Respondents should enjoy the extraordinary power of eminent domain” (at 2). The brief then repeated Miles’s arguments that the court below was wrong, claiming that “A ‘railroad company’ must be ‘operating’ a railroad – in the present” (at 2-7), that “A ‘railroad’ must include trains on tracks” (at 7-9), and that “The Court should review the court of appeals’ erroneous holding that Respondents meet section 131.011’s definition of an ‘interurban electric railway company’” (at 10-11).

The Reply brief restated the grammatical argument, too, saying that the: “context does not permit disregarding the tense of the present participle ‘operating’ in section 81.002(2). That tense fulfills a vital legislative purpose: ensuring that only companies with expertise running a railroad are empowered to seize private land to do so. It is a legislative choice” (at 3-4) and, under the holding below, “anyone could incorporate a railroad under article 6259(a) – with or without trains running on tracks (at 4, emphasis in original). The brief does not allege that Texas Central belongs in the “anyone” category or dispute its expertise, but instead calls for a “reasonable probability” text, without actually defining the actual likelihood that a “reasonable probability” would require: “Respondents plainly cannot satisfy this test. They offer nothing beyond preliminary activities involving consultants and government agencies, along with land surveys, to demonstrate a reasonable probability they will in fact be operating a railroad. They have not tried to explain how these past activities prove any likelihood they will ever actually operate a railroad, including how they will help raise the $29.5 billion they need but do not yet have. Respondents have not met their burden of establishing a ‘reasonable probability’ of success” (at 7, document citations omitted).

Miles’s Supporters Have Their Say, Too

Even before Miles had filed the Reply brief, non-parties began filing letters with the Court in amicus (“friend of the Court”) capacities, supporting him with arguments reflecting their own interests in the outcome of the case. They included the Texas Farm Bureau (filed before Texas Central’s response was), the Texas and Southwestern Cattle Raisers’ Association, and Delta Troy Interests, Ltd., owner of a tract of land near Houston.

Another party who objected to the project was an actual operating railroad, in a sense. SNCF America, an indirect U.S. subsidiary of French national railroad SNCF, filed an amicus brief on September 20 (found at https://search.txcourts.gov/SearchMedia.aspx?MediaVersionID=9a6fac2c-cb9d-4fcf-9404-f3725e2943f1&coa=cossup&DT=BRIEFS&MediaID=0ed4c7de-9fea-45a1-ad4c-d10498cbdfbb), supporting Miles’s request for review, and joining him in arguing that Texas Central should not have eminent domain authority because, according to SNCF, it would not be in a position to operate a railroad in actuality. SNCF concentrates its argument on the issue of how the Texas Central project would be financed: “The most important step for the creation and operation of a railroad is to obtain financing. To date, Respondents have not shown that they have the necessary funds or financial guarantees to build a high-speed rail system. Over the years, Respondents have asserted time and again that their project will be entirely privately financed, but the history and economics of high-speed rail make plain that Respondents will not be able to secure such financing” (at 3). SNCF also argued: “Respondents may have a cadre of contractors, consultants, and advisors, but it is Respondents themselves who are claiming to be a railroad company or interurban electric railway company, and they have no experience in the railroad or high-speed rail industry. In other words, all indications are that Respondents lack the wherewithal to convert their grand vision into reality” (at 5) and said “Bare corporate aspirations do not justify jeopardizing private property rights” (at 10).

SNCF also claimed: “To SNCF America’s knowledge, no fully privately financed high-speed rail infrastructure exists anywhere in the world. The revenue generated by high-speed rail is frequently sufficient to sustain the railway’s operation and the very expensive costs of maintaining the infrastructure, but it often falls short of what is needed to cover the initial capital investment” (at 13-14) and said: “To date and to SNCF America’s knowledge, only two high-speed routes in the world – the Shinkansen line between Tokyo and Osaka, and the TGV line operated by SNCF between Paris and Lyon, which are among the oldest high-speed routes in the world – have managed to break even, when accounting for initial infrastructure construction costs” (at 14, citation omitted). SNCF also noted: “As such, even high-speed rail projects that were originally intended to be privately financed – such as the High Speed 1 line in the U.K. and the high-speed rail system in Taiwan – have ultimately required substantial government investment” (at 14).

In addition, SNCF argued that Texas Central will not be able to build its project strictly on private financing, either, and sounded a cautionary note that could reverberate beyond Texas to the national and international stages: “With national economies sliding into the worst recession in decades, it is far from clear that this contingency will actually materialize (at 16). What SNCF did not mention was that Texas Central has developed a relationship with a Japanese HSR operator (intimated, at least, in Texas Central’s August 28 Response, at 5). This gives rise to the question of whether or not SNCF would be so pessimistic about Texas Central’s chances of success if it had formed a similar relationship (perhaps a joint venture or a significant contract for services) with SNCF, instead.

The Next Round of Briefs

Then it was time for the parties to submit their briefs on the merits. Miles submitted a 132-page filing on December 10 (found at https://search.txcourts.gov/SearchMedia.aspx?MediaVersionID=42989d3d-cf11-43ec-8282-2f693aa644a5&coa=cossup&DT=BRIEFS&MediaID=880014e4-cdae-4f44-9bdb-9979a27bf912). He repeated his arguments that the holding from the court below was incorrect and expanded the argument that Texas Central could not succeed in its efforts to build the planned railroad. For its part, Texas Central filed its own 214-page submission of its brief and exhibits (found at https://search.txcourts.gov/SearchMedia.aspx?MediaVersionID=3da75e84-bb29-4b47-89b0-308a5e916c78&coa=cossup&DT=BRIEFS&MediaID=a8f680b1-6797-47df-b24e-8b36ddcf1155). In its brief, Texas Central touted the benefits of the project and defended the Appellate court’s reasoning.

After the parties had submitted their main briefs, there were more. On January 25, Miles filed a 33-page Reply brief (found at https://search.txcourts.gov/SearchMedia.aspx?MediaVersionID=97b1e44d-c67f-4090-8461-1a67f07c73a2&coa=cossup&DT=BRIEFS&MediaID=7d3acf49-b8a0-457b-873d-64735b711442). Miles restated the arguments from his previous brief, and this time distinguished between the Texas Central project and both “operating a railroad” and “an electric interurban railrway company” in the same paragraph: “the sum of Respondents’ argument is even worse than its parts, combining two things Respondents are not – an operating railroad and an interurban electric railway – to claim eminent domain authority as a third thing for which the Legislature specifically denied such authority: a “high-speed rail. And Respondents offer nothing but empty promises to suggest that their proposed highspeed rail will ever become operational” (at 2). The same day, SNCF filed another brief, continuing to argue that Texas Central could not complete the project, particularly due to lack of funds.

Texas Central filed a 38-page sur-reply brief on February 11 (filed without any new exhibits and found at https://search.txcourts.gov/SearchMedia.aspx?MediaVersionID=d6031fee-0446-40e8-8dc4-b958988d3385&coa=cossup&DT=BRIEFS&MediaID=8ced0247-86fc-4c35-b46a-aa0c54caca07), responding to Miles’s Reply brief and restating its arguments from the prior brief. While an appellant (the party appealing the decision by the lower court) is almost always allowed to file a Reply to the Respondent’s brief, it is not common for a Respondent to file a sur-reply to the Appellant’s arguments.

The same day, Delta Troy Interests filed an amended amicus brief, again supporting Miles, and there were two more briefs that came thereafter. On February 22, Grimes, Waller, Madison, Leon, Ellis, Freestone, Limestone, and Navarro Counties filed a combined brief in support of Miles, who at one time was a Leon County commissioner. County attorneys filed the joint brief (which can be found at https://search.txcourts.gov/SearchMedia.aspx?MediaVersionID=172c8878-bbaf-4c3a-8e13-9f48c37f9ffe&coa=cossup&DT=BRIEFS&MediaID=85bb38da-03e6-463e-8a07-b7ffbcb34116). All eight amici are the counties along the proposed line, not including Dallas County or Harris County (Houston), so the counties claim that their residents would be affected by the proposed line, but trains would not stop there. The brief cited no cases; only five provisions from the transportation portion of the Code of Federal Regulations (CFR). In essence, the counties argued that the project had not received needed approvals from the FRA and the STB, that the proposed line could not succeed there, that TCRI will not be able to obtain the necessary funding, that ITL should not be a party to the action because it was established after the dispute first arose, and that there would not be any benefits for the rural counties between Dallas and Houston.

The counties invoked the urban-rural divide that is so keenly-felt in much of the country today, pitting a supposed wealthy urban or suburban elite in the Dallas and Houston areas against rural residents who live further from those cities: “In truth, the Project would benefit only a small segment of society who wish to travel between Dallas and Northwest Houston in 90 minutes and do not mind paying the same high cost of a plane ticket plus parking to do so. But those individuals’ interests (and TCRI’s) are not the only ones that matter. The interests of these very few must be weighed against the interests of Texas citizens and landowners and the rural communities in which they work and live. TCRI tries hard to paint a rosy picture of the Project’s alleged benefits, but it ignores the permanent damage it will cause to amici, small-town residents, farmers, ranchers, businesses, and the rural lifestyle that is the heart and soul of Texas” (at 3). The counties also said that this is an automobile-oriented country with low gasoline prices and taxes, and toll-free highways so, since this country has so much automobile-oriented infrastructure, it would be a bad idea to build a rail line. They also argue that the proposed line will fail, and even the Texas Department of Transportation (TxDOT) said that its ridership predictions were overstated (at 10-12).

Perhaps most telling, the counties argue that “The Project will not bring benefits to Texas or its rural communities” (at 13-14). They concede that there would be benefits for Dallas and Harris Counties [Author’s Note: at least check, those counties were still in Texas], “but not amici’s counties” (at 14). While diverting motorists onto rail of any sort is often considered beneficial for the sake of the environment and sometimes for the local economy, the counties argue that such a “successful” outcome for the proposed line would be bad for their region: “Likewise, diverting automobiles to high-speed rail would negatively impact rural businesses dependent on highway traffic along Interstate 45. These businesses also create “job years” and generate tax revenue in amici’s rural communities” (Id).

On March 19, the Texas Farm Bureau filed its second amicus brief; the last one filed in this round (and found at https://search.txcourts.gov/SearchMedia.aspx?MediaVersionID=2104f702-9597-4bd2-9a76-b75588c9dd5f&coa=cossup&DT=BRIEFS&MediaID=47849a62-a437-4064-8cf0-d2dd099817a8). They repeated their old arguments: the high burden of eminent domain for private entities and that the statutes do not grant Texas Central such authority, there is “No Objective Evidence to Show Reasonable Probability of Actual Statutory Compliance” and “The Proposed High-Speed Rail Line Will Devastate Farmers, Ranchers, and Rural Towns and Counties.” The latter argument began this way: “A high-speed rail line that would cut rural farms and ranches in half is especially onerous – the high-speed rail would apparently run at extremely high speeds and require up to 100 foot rights-of-way (a third of the length of a football field) and 40 foot embankments (as tall as a mature Texas Red Oak)” (at 21; parentheticals in original).

Like the rural counties, the Farm Bureau claimed that the line would not benefit its region and, while strongly doubting that the proposed line could succeed, also claimed that, to the extent it does, that will damage the auto-dependent region’s economy: “To add insult to injury, the rural community bears almost all of the burden of this proposed high-speed rail, but shares in very little of the benefit. It is apparently intended to be a service to and from the big cities – with only one intervening stop. The intervening rural towns and counties would be passed by, because the proposed rail line is essentially a nonstop ride from Houston to Dallas. Many of these rural towns and counties rely on passing travelers to eat in local cafés, shop in quaint antique stores, and fill up their cars at the local gas station. And because there would be only one stop along the way, the high-speed rail line would likely cause rural towns and counties to lose jobs rather than allowing those towns and counties to benefit from the burden imposed on them” (at 8-9).

Nobody filed an amicus brief asking the Court to deny review and allow the lower court decision in favor of Texas Central to stand; at least not in that round of the proceedings.

Then, on June 18, the Court gave its answer. E-mail messages were sent to the concerned parties that stated: “Today the Supreme Court of Texas denied the petition for review in the above-referenced case. (Justice Bland not participating).” That was it. The Court had denied the petition to take the case, and the victory that Texas Central had won in the appellate court would stand; or so it seemed.

Texas Central’s “victory” would last for all of seven days. On June 25, the Court sent another e-mail message to the concerned parties that said “Today the Supreme Court of Texas granted the motion for extension of time to file motion for rehearing in the above-referenced case. The motion for rehearing is due to be filed in this office on or before Friday, July 30, 2021. FURTHER REQUESTS FOR EXTENSIONS OF TIME FOR THIS FILING WILL BE DISFAVORED” (emphasis in original) Miles was going to petition for a rehearing, and the Court was prepared to allow him to do it. The day before the Court’s deadline, Miles filed his motion, and the battle was on again.

This has been a long article, but the parties and amici presented many issues in their briefs; any or all of which could also be used in a future case when somebody attempts to build a new rail line, and entrenched interests who oppose that line are willing to throw the proverbial “kitchen sink” at the line’s proponents in an all-out effort to prevent its construction. Accordingly, these are issues that deserve to be mentioned, and in the context in which they were presented to the Court. With the Court’s change of mind, it was time for the next act to be played out. We will report on how the parties prepared their case for the second battle before the Texas Supreme Court in the next article in this series.