Part 11: Texas Central Files a Pseudo Answer

Written by David Peter Alan, Contributing Editor

Since last year, I have been following the saga of the Texas Central project, a proposed high-speed rail line between Dallas and a point in the sprawl near Houston. The story had more twists and turns than a mountain railroad as I covered it last year, but the result was that the Texas Supreme Court handed Texas Central a victory, which Peter LeCody, President of the Texas Rail Advocates called “a miracle.”

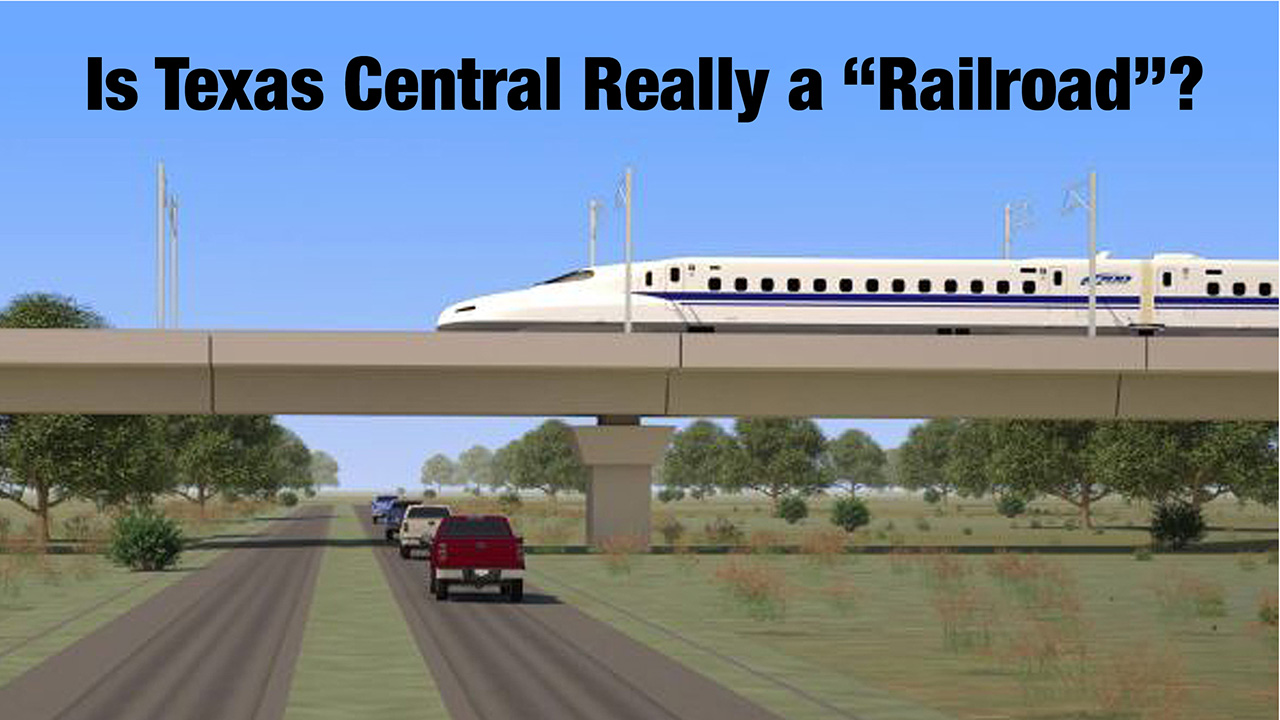

James Frederick Miles, a landowner along the proposed right-of-way, claimed that Texas Central did not have the authority to enter onto his land and survey it for possible railroad use, and he took his case all the way. In the end, the Court failed to find that Texas Central was a “railroad” within the meaning of the applicable statute, but that it was “an electric interurban railway company,” and held that it had authority to use privately owned land along its planned right-of-way under eminent domain.

Then, after the Court delivered its decision, not much happened. So Calvin V. House, another landowner in a position similar to Miles, sued Texas Central to compel the management of the proposed railroad to demonstrate that it was moving forward on its plans. As I reported in Part 10 of this series on Feb. 10, House had filed a Petition with the court in Judicial District 298 in Dallas County (which is contiguous with the City of Dallas) on January 23, which initiated the case of Calvin V. House v. Texas Central Railroad & Infrastructure, Inc., Docket No. DC-23-01174. House requested that a judge order Texas Central representatives to appear for a deposition, when they would be questioned about what steps they were taking, if any, to move the project forward toward eventual completion. House alleged that Texas Central was doing essentially nothing.

Since I last reported on this matter, court documents have been made public on the court website, www.courtsportal.dallascounty.org. Among those documents, which were submitted by counsel for House, are letters exchanged between the lawyers for the parties concerning what Texas Central has or has not done, and the questions that House’s lawyer proposed to ask Texas Central about its activities or lack of same. There were 43 such “areas of inquiry” and the list of questions looked like an Interrogatory, a discovery device where the lawyer for one side asks the opposing party a list of questions, and which the recipient answers directly. Questions of that sort can also be used for a deposition, a proceeding where a party is sworn in and questioned by opposing counsel. That is the sort of proceeding House requested, under Texas Rule 202.1(b), “to investigate a potential claim or suit” to obtain information that would determine whether Texas Central is actually progressing on its project.

Litigation procedures vary from state to state, and there is also some variation in pleadings. Some cases start with a Summons and Complaint, while others start with a Petition. The Defendant must then file and Answer to avoid being found in default. A Defendant always admits, denies or claims not to have enough information to form a belief concerning every allegation in the Complaint or Petition. Some Answers also state affirmative defenses (that the Defendant must prove), and some assert a Counterclaim against the Plaintiff or Petitioner who filed the action.

In the present case, Texas Central’s Answer was short. It consisted of a General Denial of all of House’s allegations and demanded “strict proof thereof.” The other substantive paragraph said: “Texas Central will show that the request for a Rule 202 deposition is simply an effort to re-litigate the case recently decided in its favor at the Texas Supreme Court. It will brief this issue for the Court as the case proceeds.” In a sense, that paragraph could be considered an affirmative defense on Texas Central’s part. Texas Central also asked for an award of costs and expenses, and submitted a proposed Order denying House’s request. This is standard practice in petitions and motions of this sort.

On March 1, House’s attorney also filed a Notice of Hearing that said a hearing on his client’s Petition will be held in person on Friday, April 7.

One thing I do know is that Texas Central is not dead yet; at least not entirely. Among the documents now available to the public are letters exchanged between the lawyers for the parties, which were submitted as Exhibits by House’s lawyer with the original Petition.

On Sept. 29, counsel for House wrote to Texas Central’s attorney, sending a “letter brief” that alleged Texas Central has not been active, along with a list of 20 questions and a notice of intent to call for a deposition. On Oct. 7, counsel for Texas Central replied and claimed, among other things, that House’s questions have no legitimate purpose because there is no pending litigation and that the questions “seek proprietary and confidential business information.”

House’s attorneys criticized Texas Central’s counsel on Oct. 10 for not answering the questions, but Texas Central’s lawyer furnished some information on Oct. 20. He gave a phone number and email for landowners to contact Texas Central, said that Texas Central still intends required certificates from the Surface Transportation Board, and said that eminent domain “will only be used as a last resort.” He also said that Michael Bui is in charge at Texas Central. Bui is a Senior Managing Director at FTI Consulting in Houston. According to the FTI website, www.fticonsulting.com, he is a financial manager and advisor with extensive experience in the oil and electric utility industries. His credentials include extensive experience in “turnaround management” but not in the railroad industry.

Still, Texas Central asserts that somebody is in charge, an issue that has been difficult for the prospective railroad since former head Carlos P. Aguilar stepped down last summer, shortly before the Court ruled in Texas Central’s favor.

There was no litigation pending last fall, but there is now. In his Petition, House expressed concern that Texas Central’s impending use of some of his land for its right-of-way would diminish the value of that land. In this original Petition, filed on Jan. 23, House denied that he was re-litigating the Supreme Court case, because circumstances have changed since that case began. He alleged, in essence, that Texas Central was not making the sort of progress it would need to make if it hopes to build and operate the proposed railroad, and that “Landowner is entitled to an order declaring as such so that Landowner will be able to freely use and enjoy his property without the stigma and devaluation that Texas Central has caused as a result of its promotion of the Project” (Petition at 10).

As I reported, a hearing is scheduled for Friday, April 7, and the judge will decide the issue afterward. I don’t know how the case will go, and I will report to you when I can review the decision, but there is at least some activity at Texas Central: a phone number and e-mail address, a person named as being “in charge” and a law firm pursuing the litigation on Texas Central’s behalf.

Will that be enough to overcome House’s objections and concerns? Time will tell.

David Peter Alan is one of America’s most experienced transit users and advocates, having ridden every rail transit line in the U.S., and most Canadian systems. He has also ridden the entire Amtrak network and most of the routes on VIA Rail. His advocacy on the national scene focuses on the Rail Users’ Network (RUN), where he has been a Board member since 2005. Locally in New Jersey, he served as Chair of the Lackawanna Coalition for 21 years, and remains a member. He is also Chair of NJ Transit’s Senior Citizens and Disabled Residents Transportation Advisory Committee (SCDRTAC). When not writing or traveling, he practices law in the fields of Intellectual Property (Patents, Trademarks and Copyright) and business law. The opinions expressed here are his own.