Part 10: Another Landowner Takes Texas Central to Court

Written by David Peter Alan, Contributing Editor

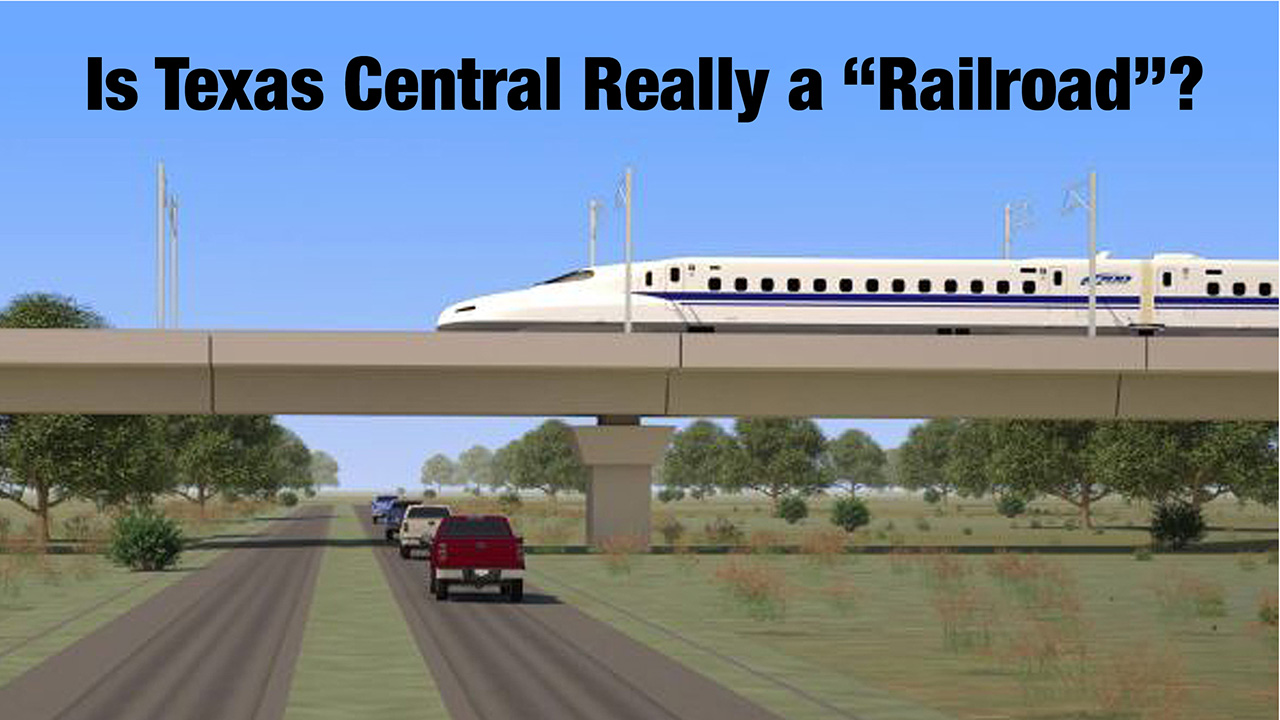

Last year, we reported extensively on a landowner’s efforts in court to stop the Texas Central project, a proposed point-to-point high-speed rail line between Dallas and a place in the sprawl near Houston, from going forward. At that time, in a nine-part series, we reported on the case’s journey through the Texas court system, and commented almost as extensively on what the decision rendered by the Texas Supreme Court on June 24 means for Texas Central and anyone else contemplating a new rail line, at least in Texas.

Now Texas Central is back in court, but in a different sort of case. As Danny Toggle reported on Feb 1, for KBTX, a TV station in Houston): “Property owners in the path of the 240-mile high-speed train that would connect the cities of Houston and Dallas are following through on their threat to take the railroad to court.” In essence, they are claiming that Texas Central is not doing anything to warrant keeping the easement on their land that it now has. The plaintiffs reside in Harris County, which contains Houston. Toggle also reported: “In September, attorneys representing nearly 100 property owners across nine Texas counties sent a letter to the rail company seeking the status of the highly anticipated project. Landowners along the route say the financial stability of the company, absence of leadership, and lack of transparency from Texas Central make it difficult to believe the project will move forward.”

Kim Roberts also reported on the letter in The Texan, an on-line news platform, on Jan. 30: “In September, counsel for the impacted landowners wrote a public letter articulating concerns and a list of questions for Texas Central Railway through its attorneys Jackson and Walker. After an exchange of letters, Texas Central’s attorney answered a few of the questions presented … Since last spring, Texas Central’s plans have been unclear to many landowners along the proposed route.” That letter was filed as Exhibit 2 with the Petition in the present case.

In the case that we covered extensively last year, James Frederick Miles, the owner of land elsewhere along the proposed right-of-way, sued to stop the project, claiming that Texas Central was not a “railroad” within the meaning of the applicable provision of the Texas Transportation Code, essentially because it was not running any trains. That case followed the sort of circuitous pattern more-commonly associated with an old-style mountain railroad than a high-speed rail line, with several twists and turns on the way to the Texas Supreme Court (Miles v. Texas Central Railroad & Infrastructure, Inc., 647 S.W.3d 613 (Tex., 2022)(Case No 20-0393)). Before the decision came down, it seemed almost certain that Texas Central had reached the end of the line.

In a surprising holding that still defies comprehension from a railroad standpoint, the Court held 5-3 that Texas Central is an “interurban electric railway company.” That means it can exercise eminent domain authority to use privately owned land for its right-of-way, in most cases by taking an easement across that land. Still, Texas Central is not a “railroad” according to the Court, because only three of its members said in a concurring opinion that it is. Advocates were glad when they learned about the decision, but not overjoyed; even though Peter LeCody, President of the Texas Rail Advocates and one of Texas Central’s most ardent supporters, characterized the Court’s decision as “a miracle.”

Little has happened since the Court handed down its ruling last June. Since we last reported to you in a commentary about the matter on July 19, it appears that Texas Central has not proceeded beyond the red signal it hit when Carlos P. Aguilar, CEO of Texas Central Partners, abruptly quit (reported here on June 15). Since then, property tax bills have been piling up, and there has been no substantive word on what the incipient “electric interurban railway company” that would run swiftly between Downtown Dallas and Houstonian sprawl is doing. Its website, www.texascentral.com, still shows posts from 2020, rather than more-recent ones. The most recent post on its Facebook page went up last March.

Against this backdrop of inactivity, Harris County landowner Calvin V. House filed a petition with the 298th Judicial Court in Dallas County to compel a representative from Texas Central to appear for a deposition, which would shed light on whether Texas Central is moving forward with its plan to build the proposed high-speed line and eventually run trains on it.

The case, Calvin V. House v. Texas Central Railroad & Infrastructure, Inc., was filed on Jan. 23, with Case No. DC-23-01174. It is captioned as a “Verified Petition for Oral Deposition to Investigate Potential Claims pursuant to Rule 202.” A “verified petition” means that the pleading was sworn before a notary prior to being filed. A deposition is a proceeding held as part of a litigation, in which a party or a witness is required to answer questions asked by the lawyer(s) for their opponents. The deponent (the person being questioned) is normally represented by counsel, and the deposition results in a transcript, which is equivalent to a sworn statement. Depositions are used as a discovery tool for fact-finding in a case, and they can also be used to attack the credibility of a witness if that witness says something during trial that is inconsistent with what they said in the deposition.

In the present case, House wishes to “take the oral deposition of a corporate representative of Texas Central Railroad & Infrastructure, Inc.” and requested a hearing (Petition at 11). The basis for House’s request is Rule 202 of the Texas Rules of Civil Procedure, which govern proceedings in the Texas courts. Rule 202.1 states in pertinent part: “A person may petition the court for an order authorizing the taking of a deposition on oral examination or written questions … (b) to investigate a potential claim or suit.” Subsequent rules govern the petition and the procedure for taking the deposition itself.

The petition, which can be found at https://www.scribd.com/document/623311644/Verified-202-Petition-against-Texas-Central-Railroad, is 12 pages long, including the verification. The filling also included five exhibits, which consisted of correspondence and e-mail communications between the lawyers representing House and Texas Central. Among them, as Exhibit 2, was the letter sent from the Landowners’ attorney on September 29. Exhibit 6 was a proposed Notice or Oral Deposition that included 43 questions (“Areas of Inquiry”) that House’s lawyer planned to ask a person of appropriate authority at Texas Central. Those questions concerned, among other things: Texas Central’s intentions, its efforts to date, property acquisition (including that owned by House as “Landowner”), financing for the project, legislative and regulatory matters, and persons with authority at Texas Central. In short, the questions asked for a comprehensive history, as well as Texas Central’s current status and activities.

The Petition itself began with the allegation: “Landowner’s potential claims arise out of Texas Central’s decade-long promotion of a now-lifeless Dallas-to-Houston high-speed rail project (the “Project”). Landowner owns property in Harris County that would be directly impacted by the Project were it ever to be built” (at 1). It recited a previous attempt by Texas Central to gain access to House’s property “to conduct surveys related to the project” (Id.). Although the Petition did not mention it, that was the issue about which Miles complained in the case that went to the Texas Supreme Court.

House then alleged that Texas Central was, in essence, not doing anything in furtherance of the goal of building the proposed line: “Texas Central never came close to putting a shovel in the ground and almost certainly never will. Texas Central has no money, no CEO, no executive leadership, no board of directors, no employees, no permission to construct, and no permission to operate. In addition, Texas Central has only a fraction of the property needed for the Project’s proposed 240-mile-long route. Despite these facts, Texas Central continues to state publicly that it intends to construct the $30 billion-plus Project” (at 2).

Then the Petition went on to claim damage to House’s title to his land: “Texas Central’s refusal to admit the obvious—that the Project is dead—has harmed and will continue to harm Landowner. Texas Central’s actions have prevented and presently are preventing Landowner from freely using and enjoying his property. For instance, Landowner cannot sell or refinance his property without first disclosing that Texas Central has stated an intent to construct the Project through his property. For these and other reasons, Texas Central’s actions continue to stigmatize and depress the value of Landowner’s property” (Id.). More specifically, the Petition later alleged: “In fact, Landowner recently considered selling a portion of his property. He learned that if he chose to do so, he would have been forced to disclose the Project’s potential impact on his property as part of the process” (at 7, n.3). While the Petition did not specify the sort of damages that House could claim, it is reasonable to assume that a parcel of land that could be subject to an easement for construction of a railroad or other piece of infrastructure would be worth less than the same parcel if the owner possesses full and absolute property rights.

The Petition then wrapped up its summary of the case by saying: “Enough is enough. If Texas Central will admit that it no longer intends to construct and operate the Project, Landowner will non-suit this Petition for a Rule 202 deposition. If, on the other hand, Texas Central continues to stubbornly insists that it intends to construct and operate the Project, Landowner respectfully requests that this Court order Texas Central to present a corporate representative for deposition to answer questions regarding any such claimed intentions. The likely benefit of allowing Landowner to take the requested deposition to investigate potential claims far outweighs the burden and expense of the procedure” (Id.).

Regarding Jurisdiction and Venue, the Petition stated: “This Court has personal jurisdiction over Texas Central because it is a Texas corporation. … No suit is anticipated, and Texas Central resides in Dallas County. Therefore, venue is proper in Dallas County” (at 3).

House then went on to lay out the facts on which he relied to make his case, grouped into subheadings that said: All facts and circumstances indicate that Texas Central is no longer pursuing construction of the Project, All facts and circumstances indicate that Texas Central will never be able to raise the $30+ billion it needs to construct the Project, Texas Central refuses to apply for a construction permit, and Despite repeated requests, Texas Central refuses to answer straightforward questions concerning the Project” (at 3-8).

House then argued (at 8-10): “Landowner has a legitimate basis for taking the requested deposition in order to investigate potential claims against Texas Central” and that “The benefit of allowing Landowner to take the requested deposition outweighs the burden or expense of the procedure.”

In arguing for a deposition, the Petition noted: “In rendering its decision, the Texas Supreme Court made clear that its analysis was restricted to the facts as they existed in August, 2018” (at 8) and then argued that time and circumstances had changed since then: “Nearly four and a half years have passed since the record on which the Texas Supreme Court made its decision closed, and the landscape has changed dramatically. Texas Central has long spent the money it initially raised and there are no signs that Texas Central has secured additional funds or financing. Texas Central has no employees. The technical experts Texas Central employed years ago have moved on to viable projects. Texas Central is no longer purchasing property along the Project’s proposed route; instead, Texas Central is selling some properties it claimed it must acquire in order to construct the Project. According to federal regulators, Texas Central hasn’t been in contact with them in years. At the state level, Texas Central has not prepared any legislation for the upcoming session and does not appear to be actively engaging legislators” (at 9, emphasis in original). The Petition continued: “In short, it does appear that Texas Central is doing some things. However, none of the things Texas Central is now doing suggest in any manner whatsoever that it does, in fact, intend to construct and operate an interurban electric railway. If that is indeed the case, it is time for Texas Central to come clean and admit the Project is over so that Landowner does not suffer further harm” (Id.).

House did not merely request a deposition. There would also be further consequences if Texas Central failed to send a representative to be deposed: “if Texas Central cannot present a corporate representative to confirm its intentions and demonstrate that Texas Central is actively taking steps to construct the Project, Landowner may seek declaratory relief against Texas Central. Specifically, Landowner may seek an order declaring that Texas Central is not planning to construct and operate an interurban electric railway” (at 9-10; emphasis in original).

Roberts reported in The Texan that, on July 8, 2022, FTI Consulting, a firm that was involved with the Project at the time, said in a statement: “Texas Central has made significant strides in the project over the past several years and we are moving forward on a path that will ensure the project’s successful development.” That was two weeks after the Court appeared to give the Project a new lease on life.

In actuality, the Court may have only given Texas Central a stay of execution. House and other landowners along the propose route are not convinced. They want to know if there is any likelihood that Texas Central can actually build the project at issue. In effect, they found no activity at the Texas Central office, and they want know if anybody is really “working on the railroad.” We will find out soon what Texas Central has to say, if anything, because the Answer is due on Monday, Feb. 13.