Moving Forward—At Restricted Speed

Written by David Peter Alan, Contributing Editor

Amtrak’s new Alstom-built Acela II trainset, seen here testing on the Northeast Corridor, is expected to enter revenue service later this year. (Gary Pancavage)

RAILWAY AGE MARCH 2022 ISSUE: U.S. high-speed rail is a mixed bag, with some projects more likely to succeed than others.

As the Obama-Biden Administration began in 2009 and 2010, “High-Speed Rail” (HSR) became a buzz-phrase in transportation circles. The High-Speed Intercity Rail Program began, but quickly went nowhere. Democrats sponsored it; Republican governors in Ohio, Wisconsin and Florida killed proposed routes in their states.

Only California planned a genuine HSR line, and that project was nearly dead three years ago. Today, it is alive again and making steady progress. So is Brightline in Florida and its subsidiary, Brightline West in Southern California and Nevada, at least as far as Las Vegas. What about the prospect of more fast and frequent service, which seemed possible for a brief moment about 12 years ago? How is the nation faring with efforts to establish high-performance passenger trains?

First, a definition. For the purposes of this article, “high-performance rail” includes passenger rail services that will achieve speeds of 110 mph or higher. This comports with the FRA’s standard for Class 6 track, where that is the top speed. Of course, it would also include faster trains on higher-tier track: Class 7 for 125 mph or Class 8 for 160 mph. The FRA allows Class 9 track with a speed limit of 200 mph, which meets the international standard for true HSR, as found in Europe, China and Japan. At this writing, there is no such track in the U.S., but a segment of it is under construction in California.

It has been a mixed bag for projects designed to deliver service at those speeds. There is an ambitious public-sector project in California, two that are being built by a private-sector company in different parts of the country, one that seems to be headed for the end of the line (not in a good sense), and some efforts to speed service on a few Amtrak routes. Every one of them is different, and some are more likely to succeed than others. Still, the prospect of high-performance passenger rail in the U.S. has moved beyond the realm of science fiction, even though it will not catapult the nation to the status of a world-class hotbed for HSR trains, like Japan, China or a number of countries in Europe.

A bit of recent history: When the Obama-Biden Administration was pushing its version of HSR, which was not as fast as the “real thing” running in Europe and Asia today, Joseph C. Szabo was Federal Railroad Administrator. Szabo “knew the railroad.” He had started on train and engine service in Chicago and had worked his way up, through his labor affiliation. The FRA sponsored a number of conferences about the Administration’s conception of HSR. Szabo remarked that it was easier to speed up a run by raising the bottom speed than by raising the top speed. Those of us who were familiar with the railroad knew this, while those who were not familiar with railroad operations probably did not, but it was Washington’s way of letting us know that applicants for grants should be looking toward what we are now calling “high-performance rail” rather than true HSR according to international standards.

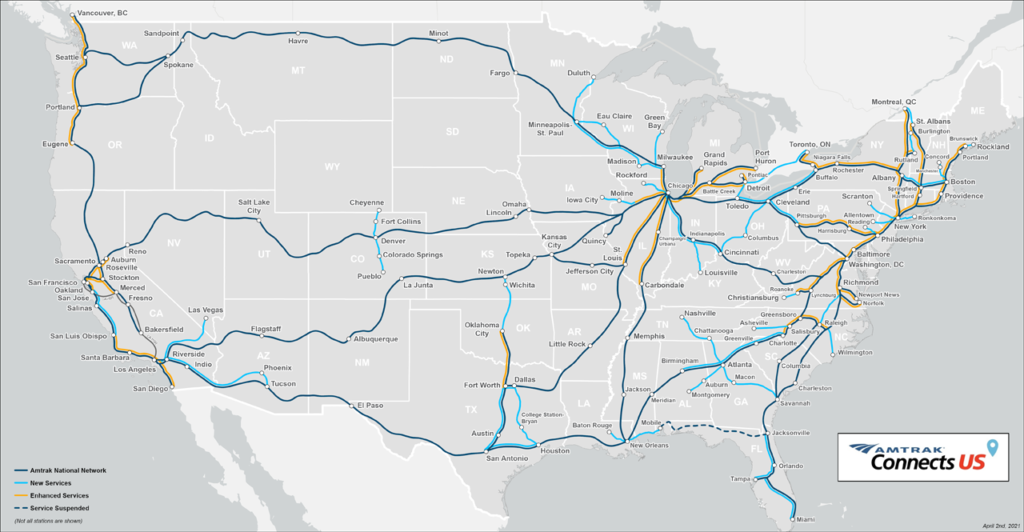

Projects in Florida (Orlando to Tampa), Wisconsin (Milwaukee to Madison), and Ohio (Cleveland, Columbus, Cincinnati and Dayton, the 3C+D) received grants from the FRA, but Republican governors turned them down. Looking back at the projects, while it would have been good to have them added to the nation’s mobility map, it does not appear that they would meet the standard for high-performance rail. The money that would have gone toward them was spent elsewhere instead, but those projects have been proposed again in Amtrak’s Connect US plan for expanding state-supported trains and corridors by 2035, which was introduced in April 2021.

There was one other grant recipient: the California High-Speed Rail Authority (CHSRA), a public-sector agency that started building a line with some true HSR mileage, the first in the nation. The project has had difficulties through the years, including three years ago, when the FRA said the project could not be completed by 2022, and “de-obligated” its $929 million grant to CHSRA. In an article on the Railway Age website, Whither (Wither) High-Speed Rail?, which expressed general doubt about the future of HSR in the U.S., I pronounced the project dead. Its circumstances have changed since then, and it is now doing better.

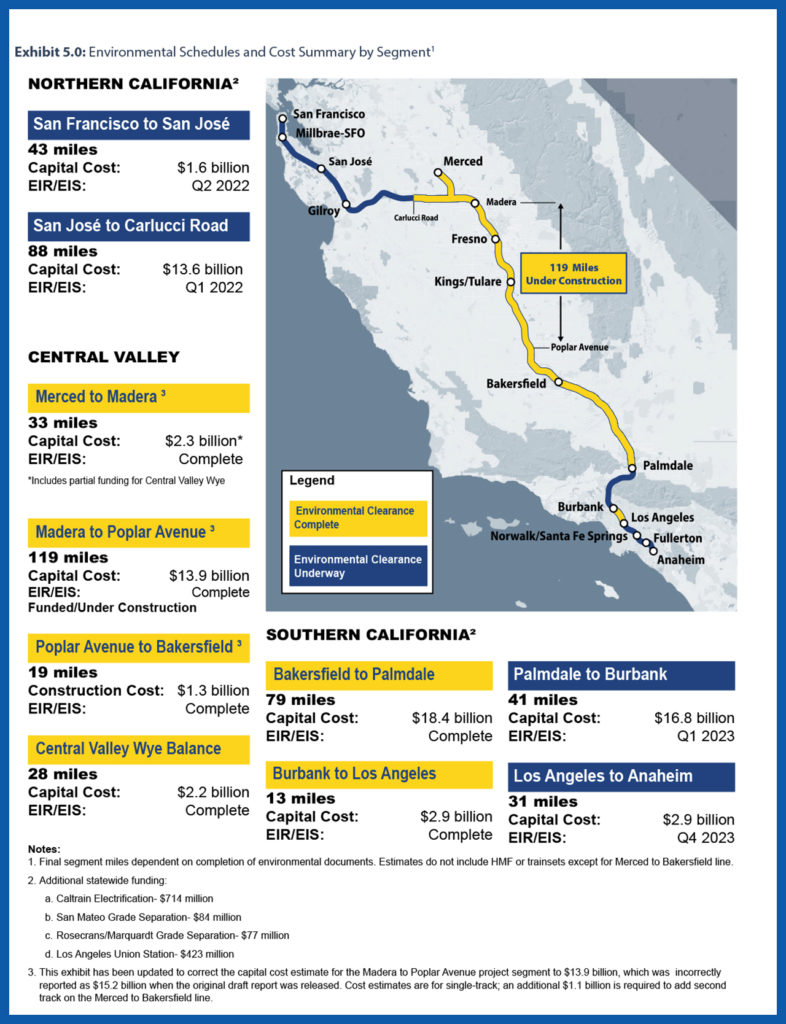

The proposed system would start with a spine between San Francisco and Anaheim, through Los Angeles (Phase 1), now slated to open in 2030. Trains will originate in San Francisco at a new station to be called the Salesforce Transit Center. From there, they will proceed along the present Caltrain line on the Peninsula to San José and Gilroy, turn left and go east through the Pacheco Pass to a point in the Central Valley (and near the current San Joaquin line on Amtrak) between Merced and Madera, and then from Madera south to Bakersfield. From there, the line would go to Los Angeles through the Tehachapi Pass and the Antelope Valley, through Burbank, and into Union Station. South of there, the last segment would go to Anaheim.

Construction is well under way in the Central Valley, with the first segment to be built between Merced and a point 19 miles north of Bakersfield. When completed, it will be the first piece of Class 9 track in the country, with a top speed of 200 mph. Plans call for a three-hour running time between San Francisco and Los Angeles when Phase 1 opens for service. Phase 2 calls for two extensions: from Merced to Sacramento on the north end, and a new route on the south end; from Los Angeles east to San Bernardino and then south through Escondido to San Diego.

The CHSRA is pursuing federal and state funding, including cap-and-trade credits. The FRA gave the CHSRA the money it started to take away three years ago, and the CHSRA is hoping to raise more money to complete Phase 1 and the two Phase 2 extensions. If the line is completed, it will be the first true HSR line in the country, possibly the only one for decades to come. If the CHSRA runs out of money, the line would not get any closer to Los Angeles than the existing San Joaquin trains, terminating at Bakersfield and requiring a bus ride to continue to Los Angeles. The cost of the entire project may be as high as $105 billion, but the CHSRA hopes it can all be built for less money. We are living in economically chaotic times, but the CHSRA expects to raise the funds.

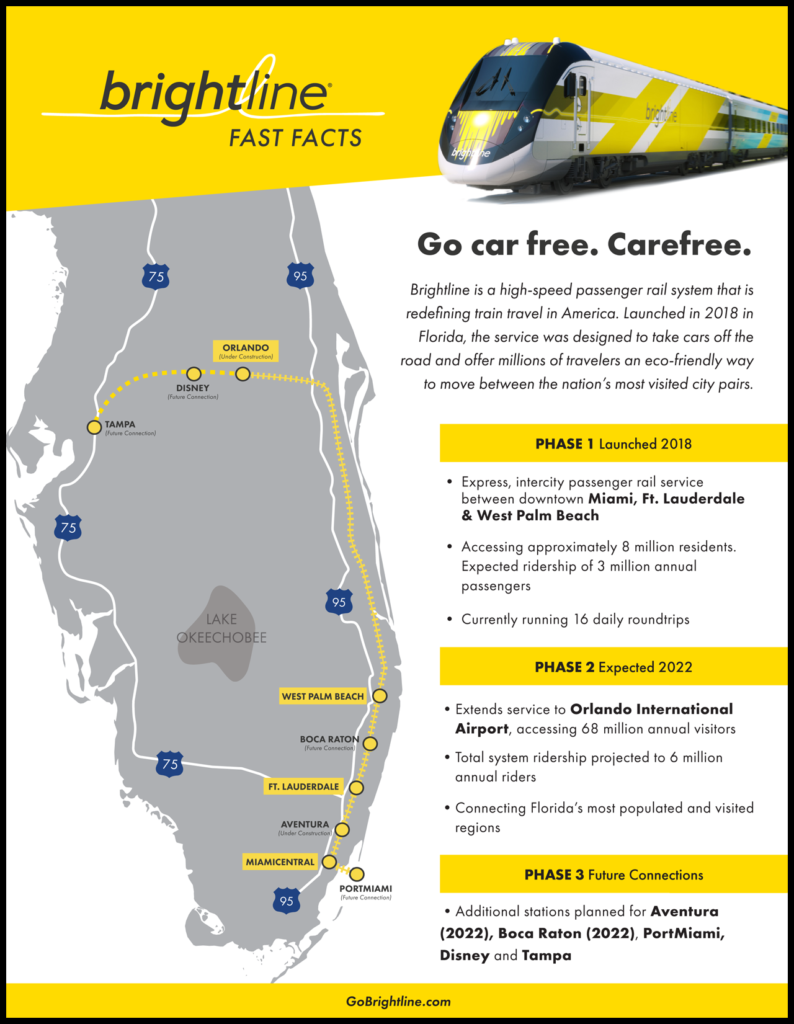

A private-sector corporation is moving forward on two fronts to establish service in two places. Brightline, a passenger start-up company, has been running fast conventional trains between Miami and West Palm Beach along the Florida East Coast Railway (FEC) and building an extension to Orlando Airport. Upgrades to the FEC main as far as Cocoa have been completed, and test runs are now taking place to familiarize crews with the railroad north of West Palm Beach. There is also construction in the area near Orlando Airport, with plans to connect to Cocoa with a new railroad built along Florida State Route 528. Brightline is looking to provide a three-hour ride, with a speed limit of 110 mph on the segment between West Palm Beach and Cocoa, and 125 mph from Cocoa until the last few miles near the airport. Plans call for service to start in 2023.

Brightline has plans for further expansion to Tampa and a station on Disney property called Disney Springs, between the two. This writer has suggested here in Railway Age that running some trains that would make additional stops between West Palm Beach and Cocoa, and eventually to Jacksonville for connections to Amtrak trains going north to New York and other Northeastern cities, would bring tourists to the east coast of Florida and increase mobility for people living there.

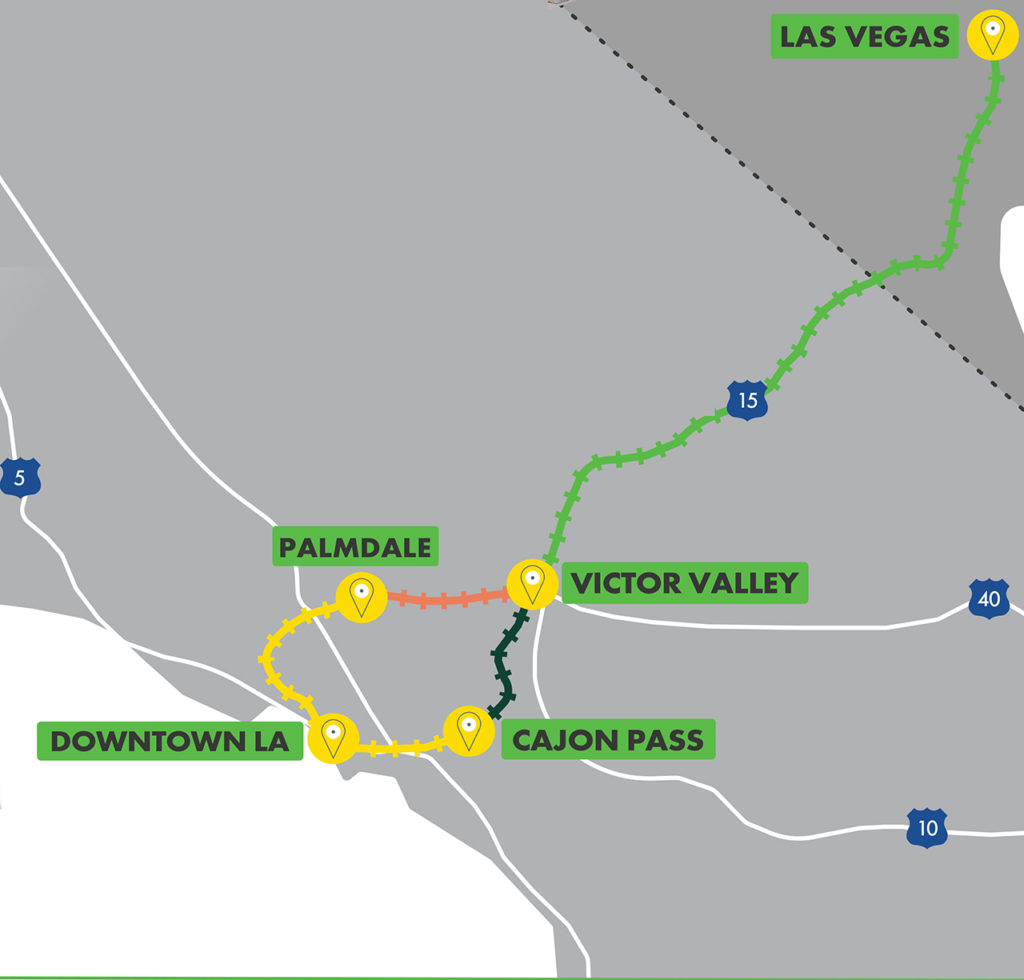

Brightline’s other initiative is Brightline West, formerly known as DesertXpress and XpressWest before Brightline bought it in 2018. The original plan was to run between a point in the Victor Valley to Las Vegas, a plan that was roundly criticized for lacking a connection to the Los Angeles Basin, a catchment area with millions of residents, many of whom do not have automobiles. Brightline West’s current plans solve that problem with a new segment that would run eastward from a park-and-ride station in the Victor Valley to Rancho Cucamonga, a stop on the San Bernardino Line operated by Metrolink, the regional/commuter rail system. Service on that line is the most-robust of all Metrolink lines; it would provide a two-seat ride between Las Vegas and Los Angeles Union Station. The top speed on the segment to Las Vegas would be 180 mph, the average speed would be 115 mph, and the trip would take two hours. With the 75-minute trip on Metrolink, trip time from the City of Angels to the gambling mecca would be 3.5 hours, faster than a trip on the highway. Brightline officials plan to run a train every 45 minutes, and service is slated to begin in 2026, an ambitious schedule for building a new railroad. There are also plans to serve the region north of Los Angeles with a line to Palmdale that would offer connections to California’s high-speed line and Metrolink’s Antelope Valley Line.

While signals appear green for Brightline, both in Florida and for Brightline West, and yellow for the California HSR project, indications are red for Texas Central, a private-sector initiative that plans to build a true HSR line between Dallas and the intersection of two highways several miles from Houston, using Japanese Series 700 Shinkansen equipment and technology. The issues are land acquisition and the demands of people who live along the potential line, but nowhere near a stop. Brightline was able to beat back a legal challenge from counties along with Florida coast where the trains would run but not stop, but Texas Central will probably not do as well. A lawsuit by a landowner may stop the line in its tracks.

James Frederick Myles, a landowner along the proposed line, objected to the railroad using his property and sued, in a case covered extensively on our website. The trial court agreed with him, the appellate court reversed and found for Texas Central, and the Texas Supreme Court turned down the case. Then, suddenly, the Court decided to take the case, invited the state to intervene, and has already held oral arguments. Republicans in the area have opposed the project vigorously, while Democrats in Dallas and Houston support it. All nine of the justices on the Texas Court are Republicans, either elected or appointed by Gov. Greg Abbott. While courts can always come up with a surprise, it appears highly likely at this writing that Texas Central is coming to the end of the line, a casualty of the rough-and-tumble world of Texas politics. To make matters worse for Texas Central, Rep. Jake Ellzey (R-Tex.) opposes the project and has introduced a bill in the House that would prohibit any HSR project from starting construction until it has acquired all the land it needs. It is unclear whether or not the bill would pass, but it could seriously jeopardize HSR, nationwide.

There are some plans for faster trains on some Amtrak lines, but it is unclear when the speed increases will occur. Parts of the line between Chicago and Detroit are being upgraded for 110-mph operation, as are parts of the line between the Windy City and St. Louis. Yet, running times on both lines have not decreased substantially in decades. It currently takes almost 5.5 hours to get from Chicago to either Detroit or St. Louis, although schedules on the latter line have been trimmed by about 10 minutes lately, for 90-mph operation. Higher speeds will require upgrades to the existing PTC (Positive Train Control) technology.

There are also places on the Northeast Corridor (NEC) where trains run at high-performance speeds. Acela trains can run at 150 mph on portions of the line in Rhode Island, while they can run at 135 mph on the Speedway in central New Jersey and at 125 mph in other areas. Conventional Northeast Regional trains run at 110 mph. There are plans for higher speeds under the proposed NEC Future initiative, an FRA process that issued a Record of Decision (ROD) in 2017, but no measures to increase train speed have been implemented. Today’s Acela trains average 78 mph between New York and Washington, D.C. and slower to Boston. The Keystone Corridor between Philadelphia and Harrisburg is rated for 110 mph.

— Moving toward a HSR future requires cultural change, not just faster trains on upgraded lines. —

Chicago advocate and railroad historian F.K. Plous raised an issue about the definition of “high-performance rail” in terms of providing enhanced mobility for riders. While speed is a component of high-performance, Plous contends that there are others, too: safety, frequency of service, reliability, and connectivity with other trains and local transit. Plous told Railway Age that true high-performance rail requires networks, not merely individual rail lines. He offered the Lincoln Service Amtrak line between Chicago and St. Louis as an example of a line where connectivity is weak. He stressed that a truly high-performance rail network is one that saturates the market by getting motorists off the highways.

Improving passenger rail performance enough to entice motorists out of their automobiles and onto the train would also improve mobility for non-motorists. The issue that Plous raises deserves serious thought, as elected officials, transportation officials, managers and rider-advocates prepare for a future that we hope will have more and better rail passenger service than the nation has today. Moving toward such a future would require more than merely planning and implementing faster service on selected rail lines. It would require cultural change.