A Varied, Growing Network

Written by David Peter Alan, Contributing Editor

InvadingInvader Wikimedia Commons

RAILWAY AGE, MARCH 2023 ISSUE: Rail transit in Northern California is on the rise.

In February, we featured the rapidly growing rail scene in Southern California, centered on Los Angeles. It is truly a transit renaissance, as rail transit went from non-existent to almost pervasive, and is still growing, over the short span of 33 years. That region and Northern California, centered on San Francisco, have historically been rivals in many ways, and they are culturally very different. Still, both regions have something important in common: Rail transit is alive and well, and on the rise in both.

Unlike the southern part of the state, Northern California has always had some rail transit. The historic cable cars have provided a unique experience in San Francisco for nearly 150 years. The city is also only one of seven in the U.S. that never lost its streetcars, and they still run today. “Commuter rail” was never a big player there—only one line, but it goes back to the time of the American Civil War.

Today, rail transit in the region exhibits a greater variety of modes than anywhere else in the nation. The San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency (Muni), which started as the San Francisco Municipal Railway in 1912, has modern light rail, historic streetcars and the unique cable cars. Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART) runs not only conventional subway/elevated cars, but also two other modes that have recently been added. There are regional trains on Caltrain, and Sonoma-Marin Area Rail Transit (SMART) north of the Bay. There is also light rail in San José, at the south end of Caltrain, and in the state capital of Sacramento. San Francisco also has ferries going across the Bay, as well as trolley buses (also known as “trackless trolleys” or “trolley coaches”) that have a double pole for contacting two overhead wires. The latter two modes do not run on rails, but they are unusual in the U.S., and add to the region’s variety of transit modes.

Before COVID-19 struck, Muni operated six light rail lines, two lines with historic streetcars, and three cable car lines, in addition to its buses. During the three years since the virus struck, we have reported to you about how rail transit in the U.S. and Canada, Amtrak, and VIA Rail in Canada have fared. Of all the cities with major transit systems, San Francisco (along with the rest of the Bay Area) was among the hardest hit. The historic streetcars and cable cars were out of service for a while, and several light rail lines were replaced by buses. The bus network shrank from 89 routes to 17, and some city locations were a mile from the nearest bus stop. The bus network is back to 47 routes (12 of which run through the night as “owl service”), and rail is coming back, too.

The hours of service and headways during the service day have not recovered to the pre-COVID levels of three years ago, but the cable car lines are back. Light rail is back on five of the six lines (the J Church, K Ingleside, M Ocean View, N Judah, and T Third Street), but not on the L Taraval, where an improvement project is under way. Historic streetcars are back on Market Street (the F Line), but not the E Line along the Embarcadero. Most of the cars in service are Presidents’ Conference Committee (PCC) cars, a design popular from the 1930s through the early 1950s. Most of those cars previously saw service on SEPTA in Philadelphia or in the Twin Cities and later on New Jersey Transit in Newark. They are painted in the colors of many systems, including several historic San Francisco liveries. There are also several Peter Witt-style “Milano” cars, which originally ran in Milan, Italy, starting in the late 1920s. A few cars are even older and come from such cities as New Orleans, La.; Melbourne, Australia; and Blackpool, England, as well as San Francisco itself. The oldest is Car #1, which began service on the original Muni system, when it consolidated the existing private companies in 1912. According to Muni, only the PCC and Milano cars are running at the present time. Although public ownership of local transit systems is common today, San Francisco was a pioneer in implementing that model.

New York has its subways and “el” trains in the Outer Boroughs, Chicago has its own “L” lines, and San Francisco and the cities and towns in the East Bay have BART. BART opened for service in 1972. Like other systems from that era, Metrorail in the Washington, D.C., area and MARTA in Atlanta, Ga., trains stop frequently in and near downtown San Francisco and Oakland, while stops are further apart in suburban towns. There are five lines that use different combinations of routes that radiate outward from the center of the system in San Francisco and Oakland.

Oakland has been considered San Francisco’s Brooklyn, with its diverse population, historic downtown (Old Oakland is a collection of office buildings from the late 19th century), and a Chinatown almost as lively as San Francisco’s. Further northwest are the towns of Berkeley, home of the University of California, and Richmond, with many reminders of World War II history and a new ferry line to San Francisco. The newest segment of BART is at the southeasterly end of the system, beyond Fremont to Milpitas and Berryessa. There are also plans to build a deep-tunnel extension further into San José. That city’s Valley Transit Authority (VTA) is building it for BART.

Much of BART looks like an elevated or surface railroad, but with broad gauge and third-rail power. There are also underground sections in San Francisco and Oakland, and under the Bay in between. It is notable that Market Street has rail transit running on three levels: historic streetcars on the surface, Muni light rail below it, and BART on a deeper level underground. It is also notable that BART has two other types of operation, in addition to the conventional “Metro” style. On the southeasterly part of the line, south of Oakland, there is a fixed-guideway shuttle between Coliseum Station and Oakland International Airport (OIA). BART calls it the Beige Line (the other lines are color-coded Red, Orange, Yellow, Blue and Green). It is cable-drawn, in a way, the descendant of the historic cable cars.

On the northeasterly line, there is a new extension called “e-BART” extending past Pittsburg/Bay Point, where the Yellow Line used to end. Now, there is a transfer platform further east, where a connection is available for a standard gauge diesel multiple-unit (DMU) that goes two stops further, to Antioch.

Heading south from San Francisco is Caltrain, a regional/commuter line, the only one in the region. The line stretches down the peninsula for 46.75 miles to San José, through such towns as San Mateo; Santa Clara; and Palo Alto, the home of Stanford University. A few commuter-peak trains continue further south to Gilroy, a town famous for growing garlic. The service began in 1863 under the San Francisco & San José Railroad, which became part of the Southern Pacific, and the route eventually settled into becoming the Peninsula Commuter service. It has experienced financial troubles through the years, most notably when COVID-19 caused ridership to plummet. Ridership remains far below pre-COVID levels, but governmental bodies have kept service going.

The California Department of Transportation (Caltrans) became involved with the operation in the 1980s: subsidizing it, naming it Caltrain, and forming the Peninsula Corridor Joint Powers Board to manage it. In the wake of the dwindling ridership after the virus struck, the counties along the line instituted a special tax to keep it going, a measure that received the two-thirds vote necessary in California. The line is now being electrified between San Francisco and San José in conjunction with the California High-Speed Rail Authority (CHSRA) project. Local trains take approximately 1 hour and 45 minutes end to end and run hourly for most of the service day on weekends. On weekdays, there are also “limited” trains that skip some stops. During peak-commuting times, there are also “Baby Bullet” trains that make the trip between San Francisco and Diridon Station in San José in 65 minutes.

San José has light rail too. VTA operates the system, which consists of three lines, color-coded Green, Blue and Orange. Each line takes about one hour for a one-way trip, end to end. Service began at the end of 1987, and the system reached its current length of 42.2 miles in 2005. VTA connects with Caltrain in four places: Mountain View; Great America; Tamien Station (the terminal for most service); and Diridon Station, the main station in town, which also hosts the Altamont Corridor Express (ACE), and Amtrak’s Capitol Corridor line to Sacramento (which uses Union Pacific right-of-way) and Coast Starlight long-distance train.

VTA has seen some hard times, especially as Silicon Valley’s fortunes began to ebb. The system’s ridership is low, and it no longer operates all night. A three-stop shuttle to Almaden was discontinued and replaced by a bus route in 2019. Sadly, a May 2021 mass shooting at the Guadalupe Yard took 10 lives. Still, VTA keeps going and does its part to provide mobility in the area.

The ACE is the smallest player in providing service in Northern California’s rail scene. It runs from Stockton (on Amtrak’s San Joaquin line) on Union Pacific (UP) right-of-way into San José four times on weekday mornings and back in the late afternoon and early evening, living up to its former name, the Altamont Commuter Express. Service began in 1998 on UP’s former Southern Pacific and Western Pacific subdivisions through scenic Altamont Pass and Niles Canyon. It takes 2:12 to traverse the 86-mile route with 10 stations. There was never service outside peak commuting periods, except for a mid-day train that ran from 2006 to 2009, and two Saturday round trips that started Sept. 7, 2019, but became casualties of reduced ridership after the COVID-19 virus struck.

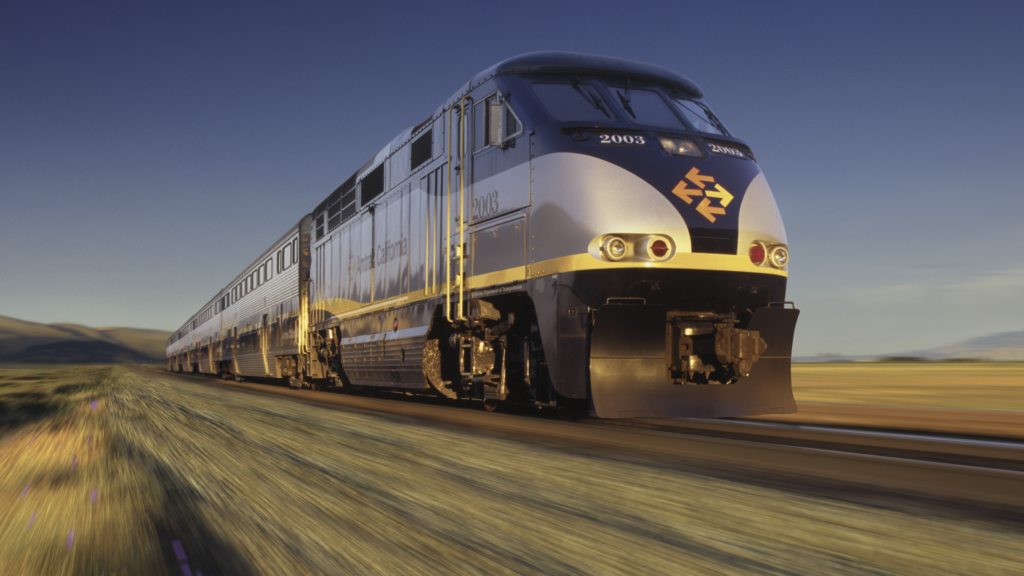

Amtrak’s Capitol Corridor connects BART, ACE, Caltrain and other Amtrak routes. It is operated by the Capitol Corridor Joint Powers Authority, in conjunction with Amtrak and Caltrans. It runs for 123 miles between Sacramento and San José, through Oakland and Amtrak’s main station at Emeryville. One round trip runs 35 miles further east to Auburn. The line began service in 1991, and runs with bi-level California Cars. Amtrak’s Coast Starlight runs along the route, while the California Zephyr runs along part of it, east from Emeryville. Service was cut to five round trips per day due to COVID-19, but is recovering. There are plans to extend the line south to Salinas, a stop on the Starlight and home of famous writer John Steinbeck.

Sacramento, the terminal for most trains and the state capital, also has light rail. The Sacramento Regional Transit District (SacRT) runs two full-service lines on a 42.9-mile system that started service in 1987. The Blue Line runs northeast and southeast of the city, looping through downtown, near the state capital. The Gold Line originates at Sacramento Valley Station, the headhouse for the main train station (although the tracks and platforms are now a sizable walk from there), eastward to historic Folsom. There is also the Green Line, a weekday short line from 7th Street in the River District through downtown. There have been plans to extend it to the airport, but the money has not become available.

There is also a proposed line in the planning stage that would host commuter trains north of Sacramento. North Valley Rail, proposed by the Butte County Association of Governments, in conjunction with the San Joaquin Regional Rail Commission, would stop north of Natomas at Plumas Lake and Marysville/Yuba City. It would either continue to Gridley and Chico, or use an alternative route to Oroville. Plans call for two daily round trips in 2028, with two more in 2030.