Why Intermodal Isn’t Everything It’s Cracked Up to Be

Written by Gil LamphereMemorandum To: CEOs, Boards of Directors, Institutional Investors

Bcc: All operating personnel, finance, marketing, HR, investor relations

From: Gil Lamphere

Subject: Intermodal – The Real Story

“Attention class! Boys and girls! Sharpen your pencils. Today you take a test. It may dictate your professional railroading legacy, and determine the future of railroading. Do not call McKinsey, Oliver Wyman or BCG on your cell phones hidden under your desk. They do not know the questions, nor the answers.

“The kick-off question is on the chalkboard: Is Intermodal Growth All it is Cracked-up To Be? Before you open your exam bluebooks, let me warn you. If you answer Yes, you get an F. If you answer No, you get a C. If you answer Maybe, But Needs a New Paradigm, you get an A. If you accurately explain your reasoning whether it’s Yes, No or Maybe, you get an A+.

“The answers are on the last three pages of your bluebooks. We have an honor code. Do not flip to these pages. You may begin!”

For CEOs, board members and institutional investors, the last three pages of the exam bluebook read as follows:

Intermodal traffic is not everything it’s cracked up to be. We get excited by its growth in carloads, particularly relative to other commodities and merchandise. We may calculate the direct variable costs of intermodal well, but we don’t calculate the indirect and fixed costs well. We don’t allocate all the expenses and capital costs intermodal should bear. We don’t calculate its OR fairly burdened (e.g. using track-miles utilized and occupied due to spacing, speed, direct and indirect costs such as maintenance, overhead). We don’t calculate its ROIC (return on invested capital) fairly burdened. We don’t have the information as investors or analysts to do so. We don’t have the analytical drive as management to make assumptions so that we don’t answer, “OR (operating ratio) by freight category can’t be calculated.”

But consider this: If my railroad only carried intermodal, what would be my OR? My ROIC? Most important, what’s my ROE (return on equity)—at market, not book—and my sustainable growth rate? Perhaps even more important, what is my TSR (total shareholder return)?

I once posed this question to Cowen and Company Managing Director and Railway Age Wall Street Contributing Editor Jason Seidl, a noted rail analyst, at his rail conference in front of 300 institutional investors: “If a railroad were to carry only intermodal, what would be its OR?” His quick and brave single-number answer matched what I was thinking: “85.”

Several years have passed since that conference. Railroad costs have declined; marketing has become more sophisticated. The answer now is probably 77.5.

Ten years before this conference, I was on the CN board and asked Michael Sabia, CFO, and Claude Mongeau, Vice President of Strategic and Financial Planning, “What is the OR of intermodal?” Being gifted intellects, they did not tell me it couldn’t be calculated. They rose to the challenge.

They came back five days later. Michael said, “Gil, you are not going to like the answer,” and then went quiet. I did not press him. I asked simply, “Can you tell me the ROIC?” Three days later, Michael said, “Gil, you are not going to like the answer even more.”

Asking these questions to these two gifted brainiacs was in response to a conversation I had with Hunter Harrison two weeks prior.

Gil: “Hunter, this OR dog don’t hunt no more.”

Hunter: “What y’all mean, this dog don’t hunt no more?”

Gil: “We gotta grow or our P/E is gonna come down and the stock’s gonna fall.”

In other words, this growth in revenues question has been around a long time without an answer.

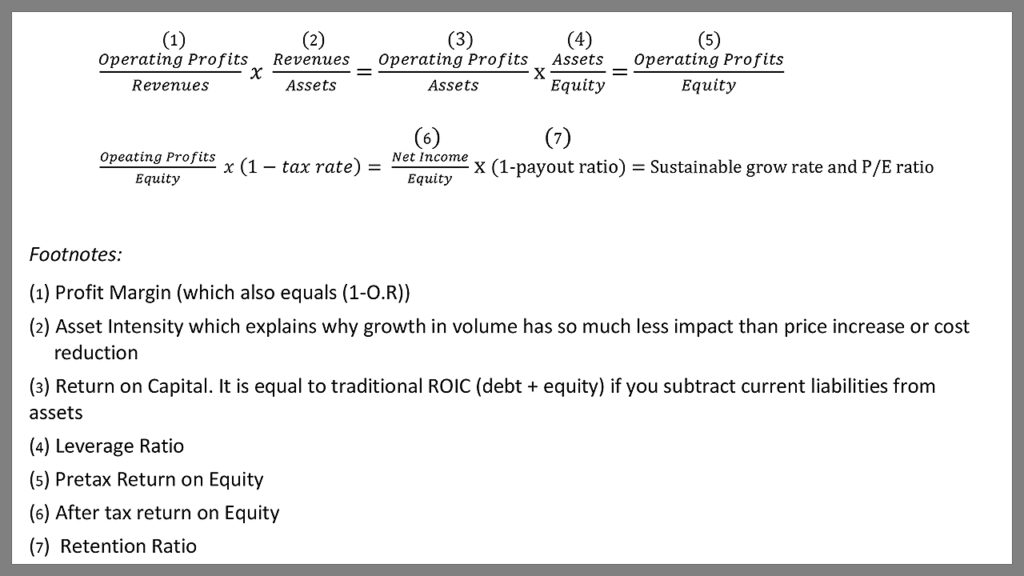

I then explained to Hunter an equation to calculate OR:

Hunter thought it was simple and brilliant. He loved that it was data and linked concepts/words he had heard thrown around but only in singular vacuums. We later presented it to the CN board at dinner to describe CN and how other railroads stacked up against CN. It showed where and how other rails generated their returns on equity.

Since OR includes both expenses and revenues, and revenues consist of both volume and price, the equation pointed out why price and expenses were so important. They fell dollar-for-dollar to the bottom line. Revenues over assetsrevealed conversely that OR and price and expenses were at least 3x more important than volumes.

This is why intermodal is such a dog. In its current form, it represents volume, but it messes with the OR and ROIC.

The other reasons intermodal isn’t great are that it is a strategic mismatch to railroads’ heavy cost/heavy load construct. Also, railroads have pricing power. Intermodal does not. Railroads have a plan and a mathematically ensured result of continuous OR improvement. Intermodal does not. Railroads’ heavy loads (bulk commodities) don’t face much competition. Intermodal faces constant competition: Trucking uses an incremental cash flow contribution, and often determines haulage and backhaul rates based on incremental variable costs like fuel and lunch money. Railroads can get away with lack of reliability, lack of timeliness, non-point to point delivery, poor first-mile and last mile. Intermodal cannot not. Intermodal promises to customers service delivery parameters that are much tighter.

Railroads need a constant, non-variable flow of goods to make intermodal operations work profitably—and even then true profits are poor. Trucks can handle variable demand volumes and time slots much more easily. This is just yet another mismatch.

The third reason intermodal is a dog, and the runt of the litter, is that it also screws up PSR. Hunter therefore hated intermodal from an operating perspective. Michael Sabia’s and Claude Mongeau’s answers made me dislike it as an answer to profitable growth.

So, for the next 20 years, most railroads concentrated on expense reduction and price. Excess cash was paid out to shareholders who could invest in growth in other sectors, such as technology, which were taking off. The dirty secret is that rail relied on 3-4% annual price increases that customers tolerate because transportation is a small part of the customers’ total expense.

If you combine those price increases with 2.5% GNP growth in commodities and merchandise and a railroad keeping expense increase under 3%, then a rail’s OR drops 0.75-1.25% mathematically and automatically. Your TSR is 13.5%-plus due to 10.5% EPS growth, plus 1.5% dividends and buybacks contributing at least another 1.5%-plus. (TSR of 13.5% assumes a sound, fair initial stock price.) If you reduce expenses and raise price, the OR declines and EPS soars.

That’s exactly what happened.

Nobody got concerned about internal growth and the tens and tens of billions in capital paid out to shareholders through buybacks, since investors simply put it to use in growth stocks.

Now, every shareholder is asking, “Can railroads grow?”

With institutional portfolio diversity and sector allocation constraints, the valuations and growth prospects of other available and former growth stocks have now shifted the questions to these: “Can railroads grow on their own?” “Is intermodal the answer, or is it a myth?”

I believe it is largely a myth under the railroads’ current physical configurations and largely limited and barely adequate service offerings. Intermodal is an incremental cash flow producer, but fully allocated costs and capital use drive you to a conclusion that slants toward the negative side of the ledger. After all, it takes 1.5-4 carloads of intermodal to equal the profitability of rails’ current mix of business, depending on whether you are in Canada, the Western U.S. or the East. (As coal’s estimated 42 O.R. slides away, the high OR of intermodal will become more apparent.)

To address this problem, it first is important to recognize that, over the next 20 years, there are three strategic stages that railroads now face:

- Years 1-5: Change nothing. Achieve TSR of 13.5% plus or minus stock market variations.

- Years 6-12: Watch OR improvements decline. Achieve TSR of 10.5%.

- Years 13-20: EPS climbs, cash flow improves. Achieve TSR of 12.0%.

So, in the short term, CEOs have to do nothing. Shareholders may clamor for this and that. They can tell or trust the CEOs to reinvest the cash flow from buybacks in other things.

Wall Street should care about use of capital, but in today’s market it focuses on EPS growth.

You think capital is almost “free”? It’s not: The cost of equity capital = TSR = 13.5%. The Surface Transportation Board and the academics need to sharpen their pencils and thinking and use market indicators, not historical accounting numbers.

But you, the CEOs, can do something, and not leave your successors to the outcome of years 6-12—in other words with a problem they have to solve. There are five strategies to grow off your current PSR operating base. All are out-of-the-box to varying degrees. Most require some or a fair amount of capex, which fortunately only slightly dents your OR.

Strategy 1: Lay new track, dedicated to intermodal. Sign shipper contracts to run eight 200-car trains a day in both directions. Operate a mix of single, double-stack and TOFC. Use the shipper contracts to leverage a separately financed intermodal subsidiary. Price at current rates. Resulting ROE? 20-25%. With the use of leverage, the equity capital commitment is not large relative to cash flow or railroad market capitalization.

Strategy 2: Use “Flexi-PSR.” Run intermodal trains that depart consistently and precisely (e.g. 8 pm, 9 pm, 10 pm, 11 pm, 12 midnight) and arrive consistently and precisely (e.g. 5 am, 6 am, 7 am, 8 am, 9 am) for immediate pickup that speeds to its point of destination on the same day. If a shipper misses the 8 pm departure, they catch the 9 pm. There is little waiting time for pickup. It is a continuous, daily, balanced flow. The trains depart on time, regardless of whether there are 50 cars or 180 cars, because it’s a premium service. When Florida East Coast employed it for several years around 2005, it had an OR of 70, won the UPS on time delivery award twice (99.49% on time arrival) and drove competing truckers (who went 70 mph on a directly parallel I-95 route over the 350-mile stretch) crazy. FEC’s ROIC was high as infrastructure expenditures matched costs. But beware! This strategy will need capex for dedicated new track/sidings to fulfill your on-time reliability promises. It will also need operational flexibility, enough locomotives to match power to variable train lengths, and train and engine crews to run the service.

Strategy 3: Establish SMART Teams. Assemble a full-time team composed of experienced personnel in marketing, ops and finance, with 2 analysts, to visit and talk to the top short line and feeder lines on which the railroad depends for first mile and last mile. Called the SMART (Short-line Marketing and Rail Transportation) team it initially visits the top 10 lines with the Class I railroad’s capex/investment checkbook in hand and asks short lines and their customers how the Class I (PSR) railroad can better interface with the short line and customer; and most important offer to help them finance projects that facilitate their transportation needs with matching funds: 1x, 2x, 3x. Often these $5-$10-$15 million investments that short lines and customers need can’t be obtained because they have limited capital, and corporate headquarters often won’t give small amounts to operating plants for non-core ancillary operations like transportation.

Strategy 4: Add slices of current bifurcated merchandise business. For example, take the existing steel reinforcing bar market. Half travels by rail, half by trucks. Use the railroads’ low OR and cost structure to carefully lower price on segments that might embrace a switch to rail. Demand no minimums. Take the risk. Take the heat about using price as a competitive weapon; because current (and projected) service levels aren’t going to entice a switch.

Strategy 5: “Proctor & Gamble” marketing strategy. Have confidence in an intermodal lane and offering that starts at an OR of 78 and good service and grows to an OR of 55 at 2x the volume with better service. The slope of the ROIC line may cause white knuckles for some during ramp-up and take some explaining to Wall Street, but take the out-of-the-box chance at changing the railroads ramp up risk profile for investment projects.

Strategy 6: Do nothing. Enjoy producing a 13.5% TSR, take little current risk, and kick the strategic can down the road to your successors. You may like this one, but will you feel guilty and be upset if it jeopardizes your chances for “Railroader of the Year”?

In conclusion, there is also a tennis match going on today that you should tune into. STB Chairman Marty Oberman is serving, using new balls and a carbon-fiber racquet for every serve. The AAR is receiving and returning, using old balls with flat spots and little bounce, and an old wooden racquet. The AAR is just blocking the serves back as best it can, and is hoping to wear out 78-year-old, highly intelligent, energetic ex-litigator Oberman, hoping he gets distracted or too busy, or that the fans in Congress and the public have to give up their seats between the afternoon and evening sessions. Matt Rose is in a box seat, too gracious to smirk or say, “I told you so.” Factor in the outcome of this match to your decision as to whether to minimize near-term risk and do nothing while trying to enjoy your TSR and stock buybacks.

“OK, students, pencils down. Time to close your bluebooks. You may now flip to the last three pages of your exam books and self-grade your exam. Remember the honor code. I have to leave the classroom now for an appointment. McKinsey is calling. They are proposing a 12-month, $2 million assignment to examine strategic alternatives for a railroad, with a $400,000 retainer. They want to know what I think. I am going to tell them to read this article and talk to a railroad’s accounting department, strategic planning, marketing and finance in the same room at the same time. Oh, it helps to have the CEO there to say, ‘Don’t be capital constrained and think outside the box, but try to get me ROEs of 13.5% if you recommend investment using capex.’”

Gil Lamphere, Chairman of MidRail LLC, has nearly 40 years of experience as a principal investor and financier in rail industry and other private equity transactions. He has headed four private equity firms and has extensive operational experience as a Chairman and/or board member for a wide range of publicly traded and private companies. Lamphere is the former Chairman of the Illinois Central Railway, Co-Founder of MidSouth Rail Corporation and former board member of CN (Chair of the Finance Committee and a member of the Compensation, Investment, and Audit committees), CSX (Operations, Finance, Compensation, and Public Affairs committees), and Florida East Coast Railway. He led teams and boards that bought, managed and changed operations at Illinois Central, MidSouth, CN, Florida East Coast and Southern Pacific, with alumni leading Canadian Pacific, creating gains for investors in excess of $2 billion.