Unknotting rail congestion compels investment

Written by Frank N. Wilner, Capitol Hill Contributing Editor

Unraveling the knot restricting rail network fluidity cannot be achieved through Surface Transportation Board (STB) intimidation of rail CEOs, or by the agency's issuance of an emergency service order instructing one railroad to operate over the tracks of another, or by merging the nation's seven major rail systems into a North American duopoly.

None would cause to appear, in sufficiently short order, the required additional locomotives and track capacity essential to curing the problem.

Congress could amend the Interstate Commerce Act and legalize discrimination as to persons, commodities and locations, whereby the STB arbitrarily embargoes some shipments in favor of others. Hmmm. Cripple the auto industry in favor of coal? Reject crude-by-rail to free up capacity for grains in storage awaiting higher per-bushel prices? Just how long would it be until Congress decides that it, rather than the STB, will choose winners and losers? Yes, that body already immobilized by political division.

Oh, were the reality of economics, law, and politics only so simple as grasping from the public policy shelf a jar of Vicks VapoRub formulated to relieve railroad traffic congestion.

The knot of railroad congestion is one of capacity constraint. It imposes costs on freight shippers, Amtrak, and the economy as a whole, plus menaces homeland security. Unraveling the knot entails added capital investment — and time.

Investment incentives still lacking

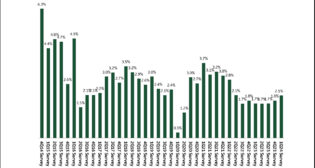

With privately owned freight railroads still not earning — or not consistently earning through a complete business cycle — their cost of capital, the incentives do not exist for a boost in the existing $26 billion annual capital investment budget. Indeed, shipper petitions for schemes intended to lower many existing freight rates would further dampen such incentives.

Yet with significant segments of the rail network operating at near 100% capacity, and predictions for accelerated rail freight and rail passenger demand to continue well into the future, added capital investment in rail facilities, devices, and equipment is essential to assure the nation’s global competitiveness, productivity, job growth, mobility requirements, standard of living, quality of life, tranquility, and national security.

On the private sector side, the medicine required from Congress and the STB is to quiet the self-serving demands of so-called captive shippers — those with few or no effective alternatives to rail transportation — whose weeping over rail service failures contradicts their assertions that freight rates are higher than necessary. In fact, captive shippers ought to be paying even more than regulators currently permit.

Were shippers to plead, instead, that, going forward, 100% of rail earnings in excess of full-business cycle revenue adequacy — yet to be achieved — be invested and leveraged in network fluidity improvements, their reasoning would be compelling. Even then, it is propitious to consider other sources of investment capital. Which brings us to the role of government and public-private partnerships.

CREATE-ive example

Consider the Chicago Regional Environmental and Transportation Efficiency (CREATE) Program.

CREATE combines funding from six Class I railroads, two switching railroads, Amtrak, a regional railroad (Metra), the City of Chicago, State of Illinois, and federal government toward some 70 infrastructure projects intended to reduce significantly rail freight and passenger delays in and around Chicago.

Note, however, that the $3.8 billion project, with an estimated $28 billion in benefits over 30 years, is less than one-third funded — and future funding is likely sticky.

Separate from CREATE, Chicago Mayor Rahm Emanuel is desperate to renew his city’s streets, parks, sewers, schools, airports and commuter rail at a price of some $7 billion. Yet Moody’s Investors Service has twice recently downgraded Chicago’s credit rating to what is now the worst among major U.S. cities other than bankrupt Detroit. The Chicago Tribune reported a “reckless pattern of borrowing” that “undermined Chicago’s future.” To stay current on long-term debt service and $19 billion in unfunded pension obligations for city workers, Chicago has raised taxes and fees faster and higher than all but four other major cities. Chicago is broke.

As for Illinois, Crain’s Chicago Business reports that despite a national economic recovery and a hike in the state income tax, Illinois “is in a deeper financial hole than ever … in worse shape than any state in the country.” There won’t be much more new rail spending coming out of Springfield.

Demand exceeds TIGER supply

As for federal funding, consider the current major source: The Transportation Investment Generating Economic Recovery (TIGER) Discretionary Grant Program. Since 2009, Congress has provided some $4.1 billion in such funds. And while the Department of Transportation recently announced the latest round of allocations — some $600 million for projects in 46 states and the District of Columbia — current applications outstrip available dollar funding a factor of 15.

Even small public-private partnerships can be problematic. In Kansas, Transportation Secretary Mike King determinedly took the lead in coordinating with the Garden City, Kans., a $12.5 million TIGER grant to upgrade BNSF track to keep Amtrak’s Southwest Chief operating through Colorado, Kansas and New Mexico. While King found another $3 million in state funds, as part of $9.3 million contributed by Amtrak and local communities in Colorado and Kansas, the State of New Mexico is yet to be on board financially. And the combined federal, state and local contributions so far are barely 10% of the $200 million estimated cost to upgrade and maintain the line for 60 mph during the next 10 years.

The Topeka Capital Journal newspaper reports that under Kansas conservative Gov. Sam Brownback, aggressive income tax cuts have resulted in “plunging” state revenue, dwindling reserves and a rare debt downgrade.” That Kansas, Colorado and New Mexico will agree to commit, for the next 10 years, $4 million annually each, with another $4 million annually by BNSF — conditioned on the state payments — is far from certain. Additionally in Kansas, the increasingly hard-pressed state is pumping some $5 million into short line railroad grants and loans.

States can’t even agree on funding to keep intercity passenger trains operating. Oklahoma and Texas officials say they are committed to financing Amtrak’s money-losing Heartland Flyer (photo at left) between Ft. Worth and Oklahoma City in the absence of federal funding. Mostly, the two states are arguing over who will pay less.

States can’t even agree on funding to keep intercity passenger trains operating. Oklahoma and Texas officials say they are committed to financing Amtrak’s money-losing Heartland Flyer (photo at left) between Ft. Worth and Oklahoma City in the absence of federal funding. Mostly, the two states are arguing over who will pay less.

Few states and fewer cities have the financial wherewithal to fund fully, and over time, rail projects — even if their state legislatures haven’t cuddled more miserly ways. As for Congress, a growing number of lawmakers embrace reduced federal budgets and lower taxes. Amtrak’s annual budget, problematic even when Democrats control Congress, faces an even greater challenge if the Senate shifts to Republican control in January.

For sure, TIGER grants will be among the casualties if Republicans control both chambers. The Obama administration requested $1.25 billion for the next round of TIGER grants, which the Republican-controlled House trimmed to $100 million. While the Democratic-controlled Senate wants $550 million as a compromise, a Republican Senate is likely to agree with the far lower House figure. Yet applications for TIGER grants cumulatively total near $1 trillion. As for high-speed and higher-speed rail funding, Republicans are adamant that not another penny in federal funds be appropriated.

The Washington situation is as fraught with complexity as stinginess. While House Republicans, more than a decade ago, combined all forms of transportation oversight into a single Transportation & Infrastructure Committee, the Senate has those responsibilities scattered — aviation and rail within the Commerce, Science and Transportation Committee; highways within the Environment and Public Works Committee; and transit and commuter rail within the Banking Committee.

Such a stove pipe approach to transportation projects make near impossible creation of a single surface transportation fund for projects national in scope and responsibility, as those educated and steeped in organizational behavior and economic efficiency would counsel.

Moreover, in the House and Senate, these are authorizing committees, meaning they make only suggestions, with final decisions on federal expenditures made by the respective House and Senate Appropriations Committee, where dollars most often are allocated absent extensive debate as takes place in authorizing committees. Indeed, it is common that appropriations are made without suggestions from the authorizing committees as the latter too frequently become deadlocked.

That’s reality.

But reality also is that transportation congestion, as mentioned, adversely affects the nation’s global competitiveness, productivity, job growth, mobility requirements, standard of living, quality of life, tranquility and national security. Also not to be overlooked is that a single intermodal train removes up to 280 pavement pummeling trucks from the equally capital starved highway system.

Multimodal model remains elusive

Congressional transportation policy has for too long, and at too great a detriment to the nation, been managed as a stovepipe affair rather than as a multimodal arrangement.

Most compelling is that public spending on infrastructure improvements generates impressive economic returns to society, according to academic studies such as Canada 2020 Think Tank. It found that $1 billion in infrastructure spending creates almost 17,000 jobs, including manufacturing, business services and transportation; increases gross domestic product by as much as $1.8 billion; boosts tax revenue by at least 30% without increasing taxes; and, longer-term, lowers production costs for business.

A Duke University study found that for every dollar invested in transportation infrastructure there is a $3.54 return in economic benefit — a multiple of almost four to one.

Privately, rail officials concede that more redundancy is needed for the nation’s rail system. Says one senior officer, asking not to be named, “What if the unthinkable occurs — a natural or other disaster or terrorist act — that takes out a crucial component of our rail network? Where is the redundancy? Where do we reroute if all other routes are operating at 100% capacity? Railroads are considered too essential to our economy and national security to permit work stoppages. Yet Congress ignores a far more pressing anxiety.”

Can someone confirm that there really is not a jar of Vicks VapoRub available to relieve all of this rail congestion? Maybe then there might be focus on practical and economically efficient solutions — a recognition that transportation in America is multimodal, acknowledgment that there must be profit incentives to encourage greater private-sector investment, and gumption on the part of Congress to participate in renewing and rebuilding crucial transportation infrastructure rather than allowing it to self-destruct and using the rubble to erect statues of Adam Smith.