“Here’s looking at you, kid,” is a cherished line from the movie Casablanca,but when the looking is through a hidden camera lens in the locker room or even visibly trained on crewmembers inside a locomotive cab, well, you won’t hear the more famous line, “This could be the start of a beautiful friendship.”

In fact, Kansas City Southern Railway, the Brotherhood of Locomotive Engineers and Trainmen, and the United Transportation Union are heading to federal court over the railroad’s announcement it intends to install inward facing cameras in its locomotive cabs as a safety overlay to monitor crew behavior and train-handling techniques.

At issue is the railroad’s quest for improved train safety and efficiency vs. a train crew’s right to privacy, as rooted in the Constitution’s First, Ninth and 14th Amendments. Courts have not always found a constitutionally protected right of privacy in the workplace, as evidenced by widespread us of cameras recording employee and patron activity in banks, restaurants, and other shops.

When Canadian National was found to have installed a hidden videotape camera in a train-crew locker room in Pontiac, Mich., in 1999, a state court ordered the camera removed on privacy grounds. CSX rethought its decision to install a hidden microphone in crew rooms. And Burlington Northern (now BNSF) was rebuked by a federal court in the 1980s when it sought to use drug-sniffing dogs to uncover narcotics in the belongings of train crews. Privacy vs. train safety and adherence to operating rules was at the core of each dispute.

For sure, substance abuse among those in safety sensitive positions is unacceptable and a clear and present risk to public safety. Following a 1987 collision on the Northeast Corridor in Maryland that killed 14 (where Conrail engineer Ricky Gates, impaired by narcotics use while operating three locomotives running light, missed a “slow” signal, ran through an interlocking, fouling the main line, and was rear-ended by Amtrak’s train 94), Congress authorized mandatory drug and alcohol testing for railroaders in safety sensitive positions. A “right” of privacy gave way to a more compelling “right” of public safety.

More recently, the use by train crews of electronic devices while on duty—such as cell phones, texting devices, and electronic games—was deemed a deadly risk made horrifically clear in 2008 when a Metrolink engineer Robert M. Sanchez, distracted while texting, ran a stop signal and slammed his packed commuter train head-on into a Union Pacific freight train in Chatsworth, Calif., killing 25 and injuring 135. The Federal Railroad Administration followed with an order banning the use by on-duty train crews of all personal electronic devices. Score another victory for public safety.

Railroads, understandably, seek every means to ensure train crews are not impaired or otherwise distracted while on duty. CN and RailAmerica went so far as to commence testing of train-crew hair samples, saying evidence of narcotics use remains in hair for up to a month vs. only a week in urine samples that typically are used in mandatory drug tests.

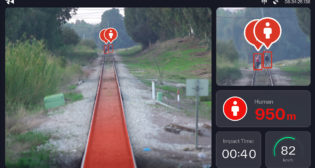

Kansas City Southern is not the first railroad to install inward facing cameras, which are intended to catch train-crews violating the electronic device ban, engaged in unauthorized napping and other unfocused or improper behavior. Los Angeles Metrolink installed such cameras following the Chatsworth collision—and there they remain. Kansas City Southern said it intends for one camera to face sideways recording actions of the engineer and conductor, and a second camera trained on the locomotive’s control panel.

Having a federal court decide the fate of inward facing cameras in the locomotive cab presents risks for the railroad and unions.

Following the Chatsworth crash, the National Transportation Safety Board recommended all railroads install on locomotives inward facing cameras. While the NTSB has no regulatory authority to enforce its recommendations—the FRA must make such a ruling—hanging heavy on the unions’ challenge is a Supreme Court decision (Chevron v. Natural Resources Defense Council) that held actions of expert federal agencies are to be given “deference” by the courts. An NTSB recommendation could be deemed by the courts as sufficient reason not to interfere with Kansas City Southern’s action.

The court may also take note that with some 163,000 miles of track, railroads operate the largest largely unsupervised shop floor in America, and that the cameras are simply a surrogate for management presence in the cab.

Still, the FRA has not acted on the NTSB recommendation, and is thought unlikely to do so under Administrator Joe Szabo, who spent much of his career as a union lobbyist opposed to privacy intrusions on his members. Yet, it was Szabo who instituted the ban on the use of electronic devices by train crews.

The unions surely will assert there are alternative, more positive and less intrusive means of supervising train crews—that railroads should devote greater energy to reducing a more common cause of accidents, crew fatigue, plus provide more intensive and remedial employee training. The unions may also point out that soon-to-be installed Positive Train Control will provide an effective safety overlay that will stop trains in the absence of appropriate action by train crews.

A potential difficult obstacle for Kansas City Southern will be the unions’ allegation that the railroad is compelled to bargain collectively over changes to existing work rules, although the railroad contends installation of the cameras is a “managerial prerogative” not subject to collective bargaining. By going to federal court to resolve the issue, the railroad avoids a threat of a work stoppage that could send fearful customers to other modes.

Whether interest-based bargaining—whereby both sides, choosing to avoid confrontation, seek mutually to solve the legitimate concerns of the other—would have produced a non-confrontational result cannot be known. However, major railroads, including Kansas City Southern, successfully engaged in interest-based bargaining prior to implementing remote control operations a decade ago.

There is another rub here. Federal regulations prohibit operation of the train by other than a federally licensed locomotive engineer. Trains do not make periodic stops to allow the engineer to use the cab’s toilet, so it is widely ignored—but not publicly acknowledged—that the engineer turns train operation over to the conductor when periodically using the toilet. With cameras, which never blink, recording every activity in the cab, the question becomes whether an engineer will halt his train periodically to use the toilet—slowing average train speeds and increasing fuel burn—or allow himself to be documented by camera of a willful violation of federal regulations that can result in suspension, dismissal, and loss of a federal license to operate a locomotive.

Inward-facing cameras are another example of the divisions and dynamics existing in today’s workplace. Yet to come—and this is a “when” rather than an “if”—is the battle, after installation of Positive Train Control, over whether freight trains can operate safely with a lone crewmember rather than the mandatory two crew members now required under collective bargaining agreements.

So, here’s looking at you, kid. Now let’s see who blinks first—or is ordered to blink first.

Tags: BLET, Brotherhood of Locomotive Engineers and Trainmen, Federal Railroad Administration, FRA, Frank N Wilner, Management, National Transportation Safety Board, NTSB, Opinion, PTC, UTU