Tank car builders don’t agree on DOT-111 obsolescence timeline

Written by David Thomas, Canadian Contributing EditorThis comes even as the White House OMB ponders whether the a 2020 tank car renewal deadline still makes any sense following a succession of challenges to the schedule’s underlying assumptions. The collapse of oil prices, the discovery that Alberta’s tar sands oil is no safe haven for aged tank cars, and Canada’s 2017 deadline for withdrawing DOT-111 tank cars from crude oil service have trashed the scenario set out in last summer’s Notice of Proposed Rulemaking.

While collapsing oil prices should slow demand for tank cars, the extreme explosivity of tar sands oil and Canada’s refusal to run a retirement home for creaky DOT-111s may impose greater urgency than before. The White House has promised a final government tank car replacement rule by this May, leaving little time to update spreadsheets with fresh assumptions and data.

The tank car timeline is part of a package of oil train reforms proposed by the DOT’s twin regulators, the Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration (PHMSA) and the Federal Railroad Administration (FRA). Tank car standards and deployment constitute the centerpiece of oil train reform, at least for now.

“A complete do-over of tank car demographics is needed, this time using confidential tank car data collected by the Surface Transportation Board and Railinc,” said Andreas Aeppli, senior associate with Cambridge Systematics, which authored the OMB submission on behalf of Greenbrier. “I was disappointed that PHMSA didn’t ask for this information originally,” said Aeppli in a March 26 interview with Railway Age. Greenbrier, like other carbuilders, is straining at the bit, waiting for final definition of a new DOT-117 tank car specification.

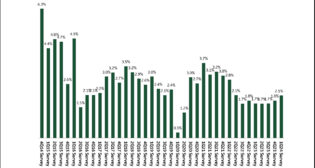

The RSI-CTC had earlier submitted a study prepared by The Brattle Group that said the proposed deadline of 2020 for withdrawal of older DOT-111 and unjacketed CPC-1232 cars would overwhelm carbuilders and overhaul shops, disrupting the continental flow of oil and ethanol. Greenbrier, challenging the RSI projection, maintained in its March 20 submission to the OMB that it and other carbuilders can make 40,000 new cars and retrofit 13,000 others annually:

“The RSI/BG analysis significantly underestimates the known capacity of the contract shop industry to meet the deadlines in the proposed rule,” Cambridge Systematics said. “Using RSI/BG’s assumptions on fleet size and retirements, along with data developed in this analysis, the retrofit process for unjacketed cars in crude oil and ethanol service can be completed in five and one-half years, and the entire fleet in six years. If implementation of the regulation is staged to address particular cars in specific service based on risk, it is possible to address the most at-risk cars—the unjacketed DOT-111 cars used in unit train crude oil service in as few as two and one-half years, even with a six-month run-up included. Contract shops and new car manufacturers will respond to changes in demand, as evidenced by announcements of shop expansions and new car manufacturing capacity, leading to substantial job creation and a safer fleet. Aggressive retrofit timelines as proposed by PHMSA for cars in crude and ethanol service are achievable.”

Interestingly, Greenbrier participated in the RSI-CTC’s Brattle Group study, supplying its own estimated production and capacity figures.

The DOT transition schedule was based on prevailing belief that crude oils vary from explosive to benign and that renewal could be prioritized accordingly, with Bakken crude getting the newest cars first. The explicit assumption was that the existing cars could be assigned to Alberta bitumen service pending retrofit or retirement. That would provide tolerable slack, given bitumen’s then-presumed reluctance to ignite in an accident.

The truth about bitumen exploded inconveniently in mid-winter when two CN tar sands trains blew up in quick succession. The pair of Ontario conflagrations revealed that, when modified for delivery, tar sands oil is far different from the viscous, barely ignitable bitumen mined or steamed from the ground.

Whether thinned with naphtha as “dilbit” or spiked with hydrogen to become “synbit,” bitumen modified for sale and transport will ignite at temperatures substantially lower than the flash points of the light crude fracked from the Bakken formation straddling North Dakota, Saskatchewan, and Montana. Scientists had already documented the volatility of processed bitumen, but that information did not come to the attention of U.S. regulators before they planned the orderly retreat of unmodified DOT-111s to Alberta’s tar sands service.

With the new understanding of modified bitumen’s extreme volatility, transferring the weakest cars to tar sands duty would be disingenuous. In any case, Canada’s prohibition of older DOT-111s after 2017 moots the strategy.

A March 24 report by the U.S. Department of Energy slammed another torpedo into the already sinking boat by stating there is no benign combination of crude oil and tank car; any oil can ignite and no tank car can contain it in a serious derailment. There is simply nowhere to hide for old DOT-111s.