Ontario Northland: Through timber to tidewater

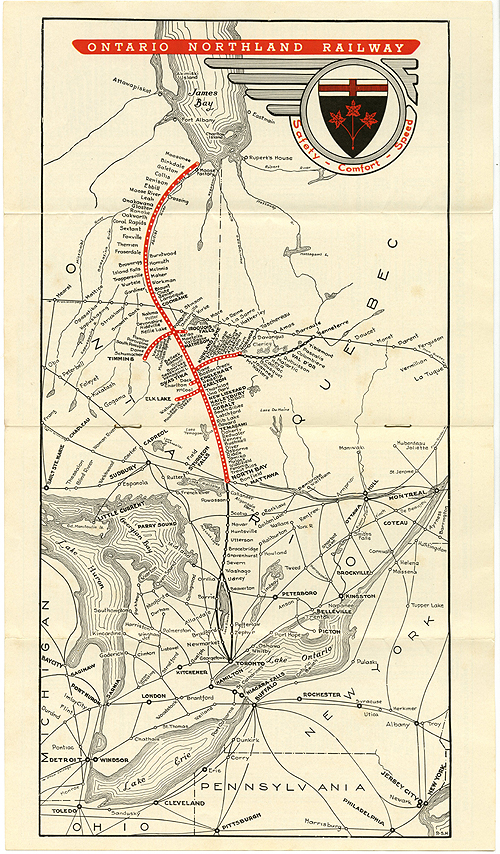

Written by John Thompson, Canadian Contributing EditorSome Railway Age readers will be surprised to learn that GO Transit, launched in 1967, was not the first venture of the Province of Ontario into the railway business; that event actually occurred some 60 years earlier. The honor actually belongs to the provincially owned Ontario Northland Railway, which links the city of North Bay, on Lake Nipissing, to Moosonee, on the salt waters of James Bay.

At that time, and until recent years, North Bay was on the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) transcontinental (Montreal-Vancouver) main line. During the past decade, the trackage between a point just east of North Bay, to Smiths Falls (60 miles west of Montreal) was abandoned.

The territories served by the two provincial railways could hardly be more different: GO Transit is based in Toronto, Canada’s largest city, and carries commuters in business attire through an area of subdivisions, apartment towers, industries and fertile farmland. Its northern counterpart, by contrast, caters to casually dressed tourists, natives, hunters, fishermen and assorted Northerners. It traverses a sparsely populated region of rock, forests, lakes, rivers and muskeg.

BACKGROUND

The Ontario Northland Railway (known as the Temiskaming & Northern Ontario Railway, T&NO, until 1946) had its beginnings in 1902, when construction began. It had been realized by the government that a railway was needed to exploit the timber and mineral wealth of Northern Ontario. A somewhat comparable project, in the western province of British Columbia, was the Pacific Great Eastern Railway, also undertaken by the provincial government. It is now owned and operated by CN.

In Ontario, transportation was also needed to bring supplies and settlers to the Great Clay Belt, a region about 200 miles beyond North Bay that possessed fertile soil ideal for agriculture.

At this time, neither the CPR, nor the Grand Trunk Railway of Canada (a CN predecessor) were interested in expanding into this region.

Construction proceeded slowly but steadily, through a challenging terrain of rock, forest and lakes, until the settlement of Cochrane was reached, 186 miles above North Bay. Cochrane was the junction with the National Transcontinental Railway, a Federal Government project, and as such provided a significant connection for many years; part of the section east of Cochrane was abandoned by CN about 15 years ago. Cochrane, by the way, is the birthplace of National Hockey League legend and coffee shop co-founder Tim Horton.

The T&NO’s construction was soon justified as silver, gold and, later, iron ore were discovered along its line. Timber was also harvested, and sent south for construction purposes. Pulp and paper mills were built to supply publishers, especially newspapers. Branches were built, as needed; some of these were ultimately abandoned as mines were exhausted. Today, the remaining branches include Noranda, Quebec, 60 miles, serving the Noranda Mining and Smelter Company; and one about 20 miles to the Kidd Creek Mine, near the city of Timmins.

In 1932, the T&NO opened its last extension, 186 miles, from Cochrane to the tiny settlement of Moosonee. This small community is located at the south end of James Bay, which is part of Hudson Bay. The rationale for the construction of the James Bay extension, a costly project through forest, rock and muskeg, was that a port for ocean freighters could be built there, and goods from the ships would be transferred onto the T&NO. However, the port never materialized, due to the Depression, World War II, and the opening of the St. Lawrence Seaway in 1959.

Yet, the railway to Moosonee does perform a vital function, bringing supplies and passengers into an area that lacks road access. In addition, supplies are transported by barge to native communities north of here. The Cochrane-Moosonee Polar Bear Express train has proved very popular with tourists anxious to see Moosonee, with its “last frontier” atmosphere.

There has never been significant on-line freight business for the Moosonee line, but the government regards its continued existence as essential, despite the deficits involved. There have been periodic suggestions to abandon the railway north of Cochrane and construct an all-weather highway on the roadbed; however, the cost of doing so has been found to be prohibitive.

The final system expansion occurred in the early 1990s, when the ONR bought 145 miles of CN trackage between Cochrane and Calstock, Ontario, just west of Hearst, northern terminus of the Algoma Central Railway. This gave the ONR access to the Spruce Falls Pulp and Paper Company, an important shipper located at Kapuskasing, approximately midway on the line. The short section to Calstock was kept to serve a lumber operation there.

At about this time there were reports that ONR might buy CN’s North Bay – Toronto line, part of which the railway wished to abandon. However, the province declined to provide funding. In any event, the only section to be removed was about 25 miles between the cities of Orillia and Barrie.

Today, ONR system track mileage totals 650. Yards are located in North Bay, Englehart, Cochrane, Hearst, Rouyn-Noranda, and Moosonee. Most of it is laid with crushed rock granite ballast and 115-pound rail, some of which is welded. The railway still performs most of the routine track maintenance, including snow clearing; capital program work, such as bridge rehabilitation, is contracted out.

Today, ONR system track mileage totals 650. Yards are located in North Bay, Englehart, Cochrane, Hearst, Rouyn-Noranda, and Moosonee. Most of it is laid with crushed rock granite ballast and 115-pound rail, some of which is welded. The railway still performs most of the routine track maintenance, including snow clearing; capital program work, such as bridge rehabilitation, is contracted out.

Engine sheds and maintenance facilities are located in North Bay, Cochrane, Rouyn-Noranda and Moosonee. The Cochrane shop is responsible for the inspection and day-to-day maintenance of the entire locomotive and passenger car fleet. This work was formerly performed at North Bay, but was transferred north to permit the main shop to focus on profitable outside work.

The main diesel shop is at North Bay, and is capable of major overhauls. The main building dates back to 1953, when ONR’s dieselization program, begun in 1946, was under way. A well-equipped car shop is also situated here. The railway dieselized with Alco, GMD and Montreal Locomotive Works units, avoiding smaller builders such as Baldwin and Fairbanks-Morse.

North Bay is also the location of the railway’s headquarters.

Despite the fact that the ONR is an interprovincial operation, it comes under the jurisdiction of the province, rather than Transport Canada. The provincial government managed to secure an exemption from federal control when the Noranda branch was built in the 1920s. And, as a provincial Crown agency, the ONR is exempt from Federal income tax.

FREIGHT BUSINESS

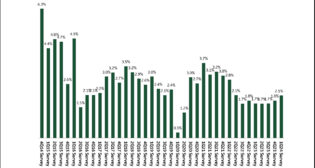

Pelletized iron ore shipments were a major source of revenue for many years, from the 1960s onward, with ONR buying specialized cars for shipping the ore to steel mills and lake ports in Southern Ontario. This business ended in 1990, when the Sherman Mine in Temagami and the Adams Mine in Kirkland Lake closed down. This resulted in a 40% reduction in tonnage, with a 25% reduction in revenue.

There was a subsequent proposal to ship garbage from the Toronto area and bury it in one of the abandoned mines. However, this idea was cancelled due to local protests, over environmental concerns.

The ONR has also experienced some losses in newsprint shipments, as the demand for newsprint in Canada and the U.S. has declined drastically due to internet competition and other factors. For example, Resolute Forest Products recently announced its decision to close its paper mill at Iroquois Falls.

At present, principal shippers continue to be within the mining and forestry industries; this section of Northern Ontario has never had a significant manufacturing base, mainly due to the comparatively small population base, compared to Southern Ontario, and the distance from the large markets there.

A strong effort is being made to attract new freight business by establishing innovative multi-modal transportation hubs, to which off-line shippers may truck goods. These include propane, lumber and agriculture-related material. The railway has added 15 new customers in recent years in these areas.

ONR’s Express Freight Service transports 7,000 to 9,000 shipments annually between Cochrane and Moosonee. These items include parcels, groceries, consumer goods and other necessities. In addition, more than 5,500 motor vehicles are carried per year on special auto carrier cars that are handled within the Polar Bear Express consist.

PASSENGER SERVICE

Until the mid-1970s, ONR ran an extensive passenger business, including sleepers serving Toronto, Cochrane, Timmins, Kapuskasing and Noranda. This service was gradually pared down until the year-round Polar Bear Express became the last survivor. The Toronto-Cochrane train was cancelled in 2012 due to static patronage and high operating costs, partly attributable to operating over CN between North Bay and Toronto. An ONR bus replaced this train.

The railway has recently been overhauling a group of former GO Transit single level coaches for use on the Polar Bear Express. These will partially replace the former 1950s vintage, ex-U.S. coaches and diners used on this operation that have become increasingly difficult and costly to maintain. Several of the older cars, however, will be retained for use during peak periods.

The railway has recently been overhauling a group of former GO Transit single level coaches for use on the Polar Bear Express. These will partially replace the former 1950s vintage, ex-U.S. coaches and diners used on this operation that have become increasingly difficult and costly to maintain. Several of the older cars, however, will be retained for use during peak periods.

The ex-GO cars were designed for short distance commuter operation, and their riding qualities suffer by comparison with conventional long-distance equipment. This was apparent on the Toronto-Cochrane service.

During 2016, more than 57,000 passengers travelled on the Polar Bear Express. The operating deficit, covered by the provincial government, was just under $16 million. The service is regarded as essential by the government, due to the link to isolated Moosonee, and the tourism benefit. The railway operates a small hotel adjacent to the Cochrane station; it has proven popular with train passengers.

EQUIPMENT

EQUIPMENT

ONR owns 24 active locomotives, as follows: five GMD SD-75s, four SD-40s, eight GP-38s, three GP-40s, and four rebuilt GP-9s (chop nosed). There are no purchases planned in the near future. ONR owns 367 freight cars, leases 78, and operates 151, through a user agreement.

CHALLENGES

The ONR has traditionally required provincial subsidies to cover its total operating deficits, both passenger and freight. Political support tends to wax and wane, depending on the party in power, the condition of the economy and other factors.

In December 2000, Canada’s Progressive Conservative government then in power, weary of the subsidies, announced that it would be privatizing the railway. Two years later, CN submitted a bid, and the government gave it exclusive purchase negotiating rights. However, in 2003 the deal collapsed over the government’s insistence on job guarantees, which CN declined to accept.

The reality is that ONR is one of the few providers of well-paying jobs in Northern Ontario, following the decline of the mining and pulp and paper industries. This is a fact not lost on the government, which is often criticized for essentially ignoring the area. That said, it was obvious that ONR’s costs would have to be reduced. In 2012, reports of another possible sale resurfaced, but were met by strenuous objections from Northern community and business leaders.

After Ontario Premier Kathleen Wynne became involved upon her election, an agreement was reached whereby the railway unions and management would develop a restructuring plan. This was completed in early 2014, detailing how the railway could be modernized culturally, with job reductions through attrition—in short, be transformed into a lean, efficient operation. The government accepted the plan. There are currently about 745 employees, located in 14 communities.

As a key element of the deficit reduction, the ONR successfully sought profitable contracted locomotive and passenger and freight car maintenance and overhaul work for its well-equipped North Bay shop. Customers include GO Transit, CN, Genesee & Wyoming, Bombardier, the Rocky Mountaineer tourist train and AMT, the commuter rail agency in Montreal. Additional employees have come on board to handle the workload; the Remanufacturing and Repair Centre, as it is designated, employs more than 200 skilled workers.

LEADERSHIP

ONR President and Chief Operating Officer Corina Moore is the first woman president of a major Canadian railway. A native of the region served by ONR, Moore joined the company in 2005 and worked her way up to Chief Operations Officer, when she helped lead the initiative to transform the company when it was threatened with defunding by the provincial government.

ONR President and Chief Operating Officer Corina Moore is the first woman president of a major Canadian railway. A native of the region served by ONR, Moore joined the company in 2005 and worked her way up to Chief Operations Officer, when she helped lead the initiative to transform the company when it was threatened with defunding by the provincial government.

Moore, one of Railway Age’s 2017 Women in Rail honorees (appearing on the cover of the November issue—the first woman on the cover in the publication’s 162-year history), was named President and COO in 2014 after serving in an interim capacity. At a company that has employed generations of area families since its founding in 1902, Moore introduced Moving Forward, a program designed to improve efficiency, grow revenues and promote the value of Ontario Northland’s transportation expertise.

Moore has teamed with employees, municipal leaders and community groups across the railway’s service territory to encourage transparency and absorb creative ideas to successfully revitalize the organization. ONR secured new locomotive and passenger car contracts, and expanded to provide freight car and locomotive overhaul and repair services to the North American marketplace.

In short, Ontario Northland is trying hard and making significant progress, a factor that hopefully will impress whichever provincial government happens to be in power.

Below: ONR’s Ceremonial Last Steam Run was operated on June 24-25, 1957, using Pacific-type locomotive 701. Here, a group of youngsters at South Porcupine witness the end of an era. The locomotive is preserved near the Englehart depot.

The author gratefully acknowledges the assistance of the Ontario Northland Railway in the production of this article.