We knew that would happen—that it had to happen—just as, and just because, the bumping block collisions didn’t have to happen.

We knew it because FRA hasn’t been able to adopt, adapt, or impose medical fitness for duty standards in the—how long?—12 years since it first put the task to the RSAC process. Twelve years? Damn, that’s as long as it’s going to take to install PTC.

FRA has had other opportunities to address obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). There was/is the risk reduction program mandated by Congress in 2008 that required railroads, under the direction of FRA, to analyze systemic risks to safe train operations, including fatigue, and provide mitigations, including fatigue management. FRA was supposed to establish the regulation governing these programs and report to Congress on progress in 2012.

Where are we with that? FRA divided the requirement into two separate programs: system safety for passenger railroads; and risk reduction for Class I railroads (and any other railroad whose safety performance FRA deems requires a program). The system safety regulation, 49 CFR Part 270, was made effective October 2016 with a compliance date, that is submission of the plan, of February 2018, a mere six years late … except FRA has delayed the effective date to December 2018, which will mean pushing back the submission of plans until sometime in 2020.

And risk reduction programs for the freights? That final rule has not yet been published.

Then, of course, FRA initiated a separate rulemaking for the testing and treatment of OSA in 2016—and then withdrew from the process in August 2017.

So, when NTSB finds in its synopsis of the investigations into these end-of-track collisions :

The failure of the Federal Railroad Administration to adequately address the issue of employee fatigue due to obstructive sleep apnea and other sleep disorders, most recently evidenced by the August 2017 withdrawal of the advance notice of proposed rulemaking, jeopardizes public safety.

That’s an accurate finding.

And when NTSB recommends that FRA:

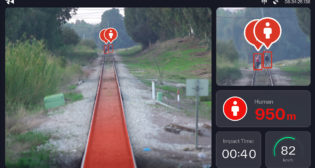

… require intercity passenger and commuter railroads to implement technology to stop a train before reaching the end of tracks.

That’s a reasonable recommendation.

Implementing a positive stop at the end of platform or station tracks does not require implementing all the functions of PTC in terminals. It can be done using either ACSES or I-ETMS based systems, by establishing in both systems a “virtual” zero mph target, like a speed restriction, or a virtual stop signal, at the end of the track.

Now, I don’t know that obstructive sleep apnea caused the collisions in Hoboken or Brooklyn. I don’t know if OSA caused the overspeed derailment at Spuyten Duyvil, but I do know we are damned fools if we don’t test and treat locomotive engineers and train conductors for OSA and reduce the risk that OSA presents to safe train operations.

That requires that everybody, including FRA, gets their heads screwed on straight.

David Schanoes is Principal of Ten90 Solutions LLC, a consulting firm he established upon retiring from MTA Metro-North Railroad in 2008. David began his railroad career in 1972 with the Chicago & North Western, as a brakeman in Chicago. He came to New York 1977, working for Conrail’s New Jersey Division. David joined Metro-North in 1985. He has spent his entire career in the operating division, working his way up from brakeman to conductor, block operator, dispatcher, supervisor of train operations, trainmaster, superintendent, and deputy chief of field operations. “Better railroading is 10% planning plus 90% execution,” he says. “It’s simple math. Yet, we also know, or should know, that technology is no substitute for supervision, and supervision that doesn’t utilize technology isn’t going to do the job. That’s not so simple.”