New Locomotive Build Market: Nonexistent for Now?

Written by Don Graab, Triangle Brothers & Associates LLC

Mark Duve photo

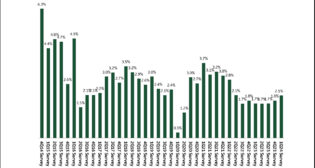

RAILWAY AGE, JUNE 2023 ISSUE: In the diesel-electric era, it’s unprecedented: It looks as though we will see three consecutive years with no new locomotives built for the North American market. This downward trend in production has been evident since late 2016 in that an average of only 77 units per year were built in the three years (2018-2020) preceding the current drought of new units. It is safe to say, in the era of diesel-electric locomotives this is unprecedented.

Fair questions to ask: “How can this be?” “Can railroads continue to buy no new locomotives?” “If so, how long can this last?”

There are numerous circumstances that contributed to this situation. Let’s begin with Precision Scheduled Railroading (PSR). Since dieselization and multiple unit (MU) control, railroads have understood longer, heavier trains reduce fuel and crew costs, which are railroads’ two primary expenses. When a lower Operating Ratio (OR) is management’s objective, you cannot beat this combination. Along the journey, the advocates of PSR realized the next lever to pull for longer trains was Distributed Power (DP), which allows the continued progression of closely matching the tractive effort of a locomotive consist to train weight, yielding lower costs. While there has been much negative publicity about the longer trains of the PSR era, DP use has many tangible benefits.

Railroads buy new locomotives for two reasons: renewal of their fleet and new business. Presently, the demand for new units generated by new business is zero. The pandemic certainly put the chill on new locomotive orders, and we have not recovered since.

Railroads are most competitive when hauling large, bulky, heavy stuff. The shift away from manufacturing to a service economy combined with aggressive “off-shoring” of manufacturing has not been kind to railroads. Significant traffic from Asia moving on land in containers has offset these losses. However, in recent years a growing amount of inbound Asian traffic has been diverted from the West Coast to the East Coast, resulting in shorter rail hauls.

Looming in the background is the continued erosion of coal traffic, which peaked in 2008. In 2022, coal production was down 49% from 2008. While you can read about surges in coal shipments, coal loadings resemble a sine wave with a steady downward slope. Traffic goes up and traffic goes down, but over longer periods of 18-36 months the trend is obvious.

On top of this, Class I carriers have a limited enthusiasm for the new Tier 4 emissions-compliant locomotives. Their higher purchase price and increased maintenance expense are a deterrent to acquisitions. Contributing to the current situation, in 2014, the highest year of new domestic deliveries since 2008, there was a surge in the purchase of road units before Tier 4 took effect (Jan. 1, 2015). About that time, significant volumes of Bakken crude oil were also moving by rail.

Returning to the fact that major railroads buy new locomotives for purposes of fleet renewal, the railroads have been more actively addressing the health needs of their locomotive assets than it may appear. For the first time in 65-plus years of diesel freight operations, the “capital” rebuilding of road units has surpassed new locomotive purchases for fleet renewal.

Let’s expound on capital rebuilds. Unlike the more routine engine overhaul, which is “expensed” from the annual operating budget, rebuilds are a life extension event where the cost is funded from the capital improvement budget. Upon completion of the rebuild, a locomotive asset is depreciated over its now-longer useful life. Notable programs from the past include Illinois Central’s “Paducah Rebuilds” where GP9 locomotives were upgraded to GP10 models; Sante Fe’s program at Cleburne, Tex., where U30C units were rebuilt as C30-7 locomotives; and other programs including work performed at Conrail.

The rebuilding activity that has taken place more recently is not fundamentally different, just far more pervasive. With a bias from my long-time employer, I would suggest that the current level of enthusiasm for capital rebuild programs started with Norfolk Southern (NS) under the direction of then-CEO Wick Moorman. Witnessing the complete rebuild of yard and local units in Altoona, Pa., and facing the huge capital requirements of PTC plus a large aging Dash 9 fleet, Moorman advocated leveraging the shop capabilities to offer a lower capital alternative for fleet renewal. This focused NS shops on the rebuilding of road units, but NS included AC traction as part of its vision for the future of rebuilt road power. This generated pressure for the two locomotive builders to participate, and both Progress Rail and GE Transportation (now Wabtec), with their aging SD70M and C44-9W DC models, were soon actively engaged. While the first Dash 9 units to emerge with AC power were delivered to BNSF, programs from both builders quickly followed at NS. Later, this concept expanded to include upgrading or rebuilding of first-generation AC units.

All the Class I railroads have participated in this capital rebuild activity, although neither BNSF nor Kansas City Southern have been active recently. While this rebuild process was originally envisioned to convert DC road units to AC traction motors (sometimes referred to as DC2AC conversions), most units processed thus far are what is often called “AC upgrades.” In other words, first-generation AC units (such as the SD70MAC or AC4400) were upgraded, retaining their AC traction motors.

Let’s go into more detail about how this works. Both locomotive builders adopted a strategy where the operator’s cab and inverter (electrical) compartment are replaced with new modules. In this way, existing assembly lines are used to produce configurations for both modules that are identical to those for new locomotives. This results in a new microprocessor control system, new relays, power contactors, wiring, IGBT inverters, electronic air brake systems and associated hardware such as air conditioning and cab seats. The diesel engine, traction motors, traction alternator, air compressor, and sometimes the truck assemblies are also rebuilt, after which the locomotive is painted and sometimes renumbered. From the viewpoint of an operator, the locomotive looks and feels like a new unit. The additional useful life of these renewed assets is estimated to be 15-20 years. It is believed these capital rebuild locomotives have demonstrated reliability equal to new Tier 4 locomotives at 50% of the cost.

A person looking at a graph of new locomotive production in North America might logically ask, “Is this trend sustainable?” Barring additional locomotive emissions regulations, the answer is “yes.”

Despite the prospects of “reshoring/nearshoring,” we are a ways off from seeing a resurgence of heavy manufacturing in the U.S. and any associated uptick in rail traffic. Currently, there are few signs rail traffic is facing a rebound. In fact, statistics reveal just the opposite. Further, coal traffic will continue to decline while many first-generation AC locomotives remain viable candidates for capital rebuild programs. Railroad managers sense the current locomotive technology has reached a plateau where it is not changing much. Railroad management, conscious of ambitious Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) goals, are anticipating the conversion to alternative fuels, namely hydrogen. A few are even expecting the next round of new locomotives to be driven by hydrogen fuel cells, not Internal Combustion Engines (ICE).

One of the unexpected consequences of the capital rebuild activity could be a spike in new locomotive demand. This would occur when locomotives that were new and never rebuilt age out at 20-25 years of useful life during the same year or years capital rebuild units reach the end of their second life. In other words, at some point, the retirement of shorter-life rebuilds is likely to coincide with the retirement of the new units that were built before rebuilding became popular. This will result in a peak demand for new power around the years 2034-2038. The likelihood of this occurring depends on capital rebuild life. The shorter the second life, the more likely a spike in demand. If the useful life of the rebuilt units turns out to be the same as the life of new units, no spike in demand will take place.

Predicting the demand for new locomotives is difficult. This is not the first time a change in operating practices has resulted in a large decrease in new locomotive production. But it is the first time production dropped to zero. What we know from the past is that locomotive demand often increases rapidly with little warning. When it does, it seems like the big railroads all want new locomotives at the same time.

Historically, railroads chose to retire locomotives based on issues with the diesel engine or overall locomotive reliability. When new diesel engines offer little fuel savings advantage, railroads are more willing to restore engine longevity with overhauls. When overall locomotive reliability declines, it is often driven by declining traction motor reliability. Rather than buy new traction motors, railroads have chosen to buy new locomotives, because replacement traction motors are quite expensive.

If new locomotive demand soars, it could easily exceed supply for a period of months or years. If prices soar as well, overseas builders could gain interest in the North American market. The flow of component parts such as traction motors may be impacted by increased production of electric vehicles and the competition for copper. Based on recent experience, the availability of skilled workers to assemble locomotives may be another looming challenge.

At some point, we will see a rebound in the demand for new locomotives. Presently, no one knows when this will occur. But the longer the resurgence is delayed, the more likely the return to new unit production will initially be a bumpy road for the railroad industry.