Central Valley Intermodal Options

Written by Jim Blaze and Chip Kraft

BNSF photo

Editor’s Note: This is the second part of Jim Blaze’s review of market challenges surrounding rail intermodal. It continues the examination of issues highlighted by Gil Lamphere in an April 2022 article. Here, Jim, in an independent view with insight from engineering colleague Edwin R “Chip” Kraft, summarizes the challenges ahead toward 2025 to 2030 by examining closely one of the West’s largest U.S. markets—the California Central Valley. How might intermodal work there?

Can intermodal rail be all it has been cracked up to be? What are the real market risk/reward choices for intermodal markets like inland California’s Central Valley?

California and other states want to shift freight from highway to rail for environmental reasons. The challenge is to understand how these environmental visions can be implemented to become a sustainable public/private enterprise venture. The business model must be economically self-sustaining.

This means that it must produce an acceptable return on capital investment, and day to day operations must also generate a positive cash flow for any private sector operator. These are the two criteria laid out in the Federal Railroad Administration’s 1997 report, High-Speed Ground Transportation for America: Commercial Feasibility Study Report to Congress, which lays out economic preconditions for the success of public/private partnerships. While it’s focused on passenger rail examples, its economic principles can be applied to any PPP, including freight rail.

The two criteria proposed by the 1997 report:

- The project must produce a positive operating ratio: Operating revenues must exceed operating costs. This is a sensible requirement for involving the private sector in a project. Typically, funding authorities such as state legislatures quickly tire of the need for providing continuing operating subsidies. Even worse, long-term losers often end up with deferred maintenance requiring capital subsidies as well. That’s always a bad financial model for a PPP. In general, PPPs should be able to cover at least their own operating costs and generate an operating profit, as well as be able to make at least some contribution to capital costs. This should be an essential first planning assumption for California.

- The project must produce a positive cost/benefit ratio: The economic benefits of the project must exceed its combined operating and capital costs over the lifetime of the project. However, the cost/benefit ratio (employed by the public sector) is much more flexible than the financial criteria employed by the private sector. To recognize a benefit, the private sector must be able to actually monetize a benefit. For example, Southwest Airlines can only recognize fares actually charged. The public sector, however, can include non-cash benefits like Consumer Surplus and various types of Resource and Environmental benefits in its calculations. Additionally, the public sector’s interest rate (cost of capital) is usually much lower than that for a private-sector enterprise.

A positive cost/benefit ratio means that the project improves overall economic welfare, and thus becomes a worthwhile project for society to invest in. Therefore, with a realistic business plan, rail companies will likely be willing partners with the state. Here is why: The Association of American Railroads position on PPPs is that “with public-private partnerships, the public entity devotes public dollars to a project equivalent to the public benefits that will accrue. Private railroads contribute resources commensurate with the private gains expected to accrue. As a result, the universe of projects that can be undertaken to benefit all parties is significantly expanded.”

The rail industry position on PPPs opens the door to a new approach to funding them, particularly intermodal projects that will produce a strong set of public benefits by getting trucks off highways.

California Central Valley Case Study

California is starting to get more aggressive in looking for an inland port strategy for linking its highly populated Central Valley with its own major ports. California has a huge local market with nearly seven million living in the Central Valley alone. However, it’s too short of a distance (less than the traditional rule of thumb, which requires a minimum 750-1,500 miles length of haul) to make a privately funded intermodal service profitable enough to invest in.

Speaking as an economist, that high localized population density is perhaps the most critical potential success factor. Why? Because as a long-distance main line intermodal railroad, you want your service hubs to be as close as possible to points of consumption and a manufacturing/assembly market. The closer a railroad can get, the lower drayage costs, the higher the line haul rate can be and remain competitive on an origin-to-destination basis.

Containers moving directly by rail from ports fully eliminates the drayage cost at one end, which gives rail an even stronger advantage, which in turn should reduce the minimum required length of haul.

Experience from others like Larry Gross further points out the critical role that drayage plays in an intermodal operation. Intermodal requires a reservoir of drivers and a reasonably efficient and short-distance highway network. A shortage of drayage drivers has been identified during the recent pandemic as a significant supply chain problem. And longer drayage deliveries add to truck driver shortages, as well as to local highway capacity and air pollution problems.

However, that’s not how a Class I railroad like Union Pacific or BNSF might see it. Railroads are looking to optimize rail line haul efficiency and simplify their operations, while local planners (and intermodal customers) are looking for convenient access to nearby rail terminals. This creates tension between local planners, railroad customers and the railroad companies as to what are the most critical factors for siting an intermodal terminal. The parties don’t see the problem the same way. Railroads seem willing to rely on longer drayage distances in order to concentrate volumes at major hubs, even at the expense of lower line-haul freight rates. The railroads’ strategy of using long-distance truck drayage to concentrate volume increases the required minimum length of haul even beyond 1,500 miles before intermodal traffic can become profitable.

However, from an economic perspective, distance differences are so critical that economists like me consider distance squared to be the actual competitive force at play between competing site locations. Translation: a site like western Barstow has plus marks for cheap land values and easy, low-cost train pull-in/pull out operations—but high distance friction (d2) when draying to/from Central Valley customers. Barstow may not be an effective location from which to distribute Los Angeles port traffic to Central Valley customers.

Choosing California’s Alternative Terminal Sites

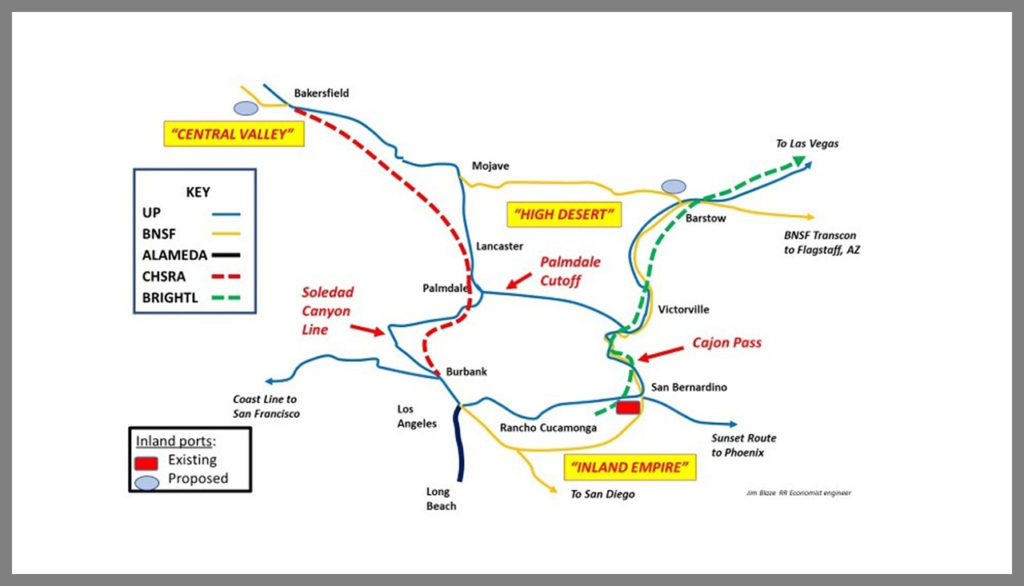

Here is a view of the current California inland intermodal location options in two maps. The first map provides a closer look at the southern part of the potential Central Valley inland port rail network. Also noted is the pattern of existing and possible intermodal terminals along the southern part of this populated marketplace:

The proposed high-speed rail (HSR) California line is shown in red while the higher-speed rail (HrSR) speed Brightline passenger route is shown in green. Those are not designed for heavy rail freight use. But let’s consider the possibility of enhancing short-haul intermodal freight service if the proposed but not yet built HSR tunnels near Los Angeles were engineered to accommodate nighttime intermodal trains. Who speaks to that intermodal option, if not the California High Speed Rail authority (CHSRA)? Might CHRSA want to join this market opportunity following the example of the Swiss Gotthard and Ceneri Base Tunnels by running a European-style container shuttle using its new tunnels under Tehachapi Pass?

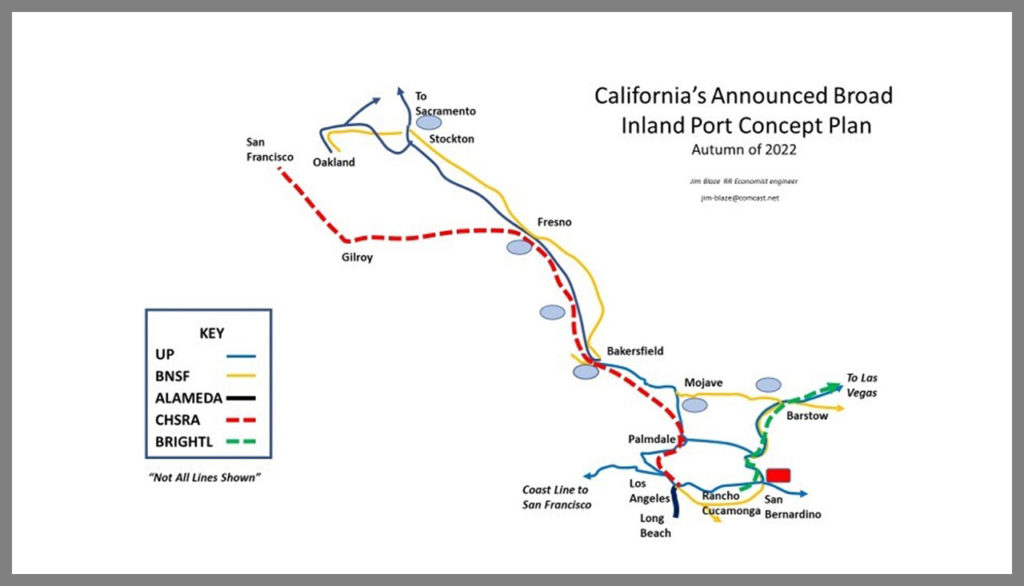

The second map illustrates where the principal intermodal rail lines are located along the entire Central Valley up toward the Oakland Bay market:

These maps point out the critical role that optimizing truck first-mile/last-mile drayage will play in any evolving intermodal plan. As compared to only having a Barstow intermodal terminal, ask yourself: which of these terminal concept plans optimizes drayage distances into the Central Valley? Finding a solution that will work for customers is every bit as important as optimizing the rail operation, if the public sector’s goal is to maximize market penetration of rail intermodal.

What is the Most Critical Hurdle?

For the public sector, because of the heavy burden of terminal capital costs, a mechanism is needed whereby the public sector can level the railroads’ capital costs for competition against highways, by covering rail terminal costs as well as the development of necessary line-haul infrastructure improvements, such as further boosting the capacity of the Tehachapi Pass rail line.

For the private sector, the most critical hurdle might be within the board room. The railroad directors’ spreadsheets suggest you only make money (on a fully allocated cost basis where the railroad provides all the capital) if intermodal trains move 750-1,500 miles or longer distances. Terminal loading, train and car switching, and container and semi-trailer handling are not where railroads make money. So, how does this private enterprise cost structure get addressed with that kind of thinking?

Not seeing the money-making potential of high-volume but short-haul intermodal traffic, Class I railroad executives and their boards remain mostly disinterested in short-haul intermodal. And since the public sector is uneasy and inexperienced in working with railroads on developing needed rail terminal and line haul capacity and feel they might get taken advantage of, little gets done. If not one of the Class I’s, who else might be the new intermodal transformation leaders?

The most likely leader in developing a network of California Inland ports will be the port authorities, which might just purchase selected location-zoned land and operate the inland facilities themselves. The Virginia Port Authority does this at its Front Royal inland port, which could become a model for how California ports might also operate.

Ports would need to fund the inland site purchases and develop them using the port’s own bonding authorities. However, operations might be subcontracted out to third parties, warehouses or logisticians. The port could even get its own trainsets to make sure it has enough cars and locomotives for use in shuttle services.

If California ports were willing to make these capital investments, they could make the business model work for the freight railroads. For more than 30 years now, Norfolk Southern has been happily shuttling containers just 220 miles to Virginia’s inland port in Front Royal. However, there is also a substantial “public” benefit to this proposal. To make the financial model work for the port authorities, CalTrans and other state agencies may also need to support the ports in planning and promoting this vision if they want to see it happen.

Wrap-up

Given the likely capital costs needed for terminals, equipment and rail line capacity enhancements, it is unlikely that the freight railroads would find developing short-haul intermodal an attractive private sector investment. So whatever California is going to design for linking its Central Valley to the ports, the system must be sized correctly and deliver a reliable service to shippers. There are ways to build this for commercial success, but not by using conventional rail intermodal constructs. To successfully deliver this kind of project, one is going to need a broader economic framework such as the PPP partnership model provided by FRA’s 1997 Commercial Feasibility Study.

Independent railway economist and Railway Age Contributing Editor Jim Blaze has been in the railroad industry for more than 40 years. Trained in logistics, he served seven years with the Illinois DOT as a Chicago long-range freight planner and almost two years with the USRA technical staff in Washington, D.C. Jim then spent 21 years with Conrail in cross-functional strategic roles from branch line economics to mergers, IT, logistics, and corporate change. He followed this with 20 years of international consulting at rail engineering firm Zeta-Tech Associated. Jim is a Magna Cum Laude Graduate of St Anselm’s College with a master’s degree from the University of Chicago. Married with six children, he lives outside of Philadelphia.

Edwin R “Chip” Kraft has been in the railroad industry for more than 40 years. Starting as a brakeman for Conrail in 1978, he worked for Conrail, Chessie System and CSX before returning to school for his Ph.D. He then worked for Amtrak in IT, Finance and in the Mail/Express group before joining Transportation Economics & Management Systems, Inc. of Frederick Md. as Director–Operations Planning. He holds undergraduate degrees in Civil Engineering and Economics and a Ph.D. in Systems Engineering, all from the University of Pennsylvania