Union Pacific re-thinks Brazos Yard timing

Written by Jim Blaze, Contributing Editor

Recent increases in Union Pacific train length as its PSR operation design is implemented. This plot represents system-wide average train lengths. Many main line trains are far longer than the graphed 7,400 or so feet.

Union Pacific contractors were moving lots of dirt when this reporter visited the Brazos Yard site in Texas in November 2018. The location was to be the new crown of UP’s capabilities to improve and increase volume and service to the expanding customer base in the Houston and Gulf Coast chemical and petrol industry complex.

In early April 2018, Railway Age, in an interview with CEO Lance Fritz, found the railroad team confident that its “network capacity is adequate overall, but we face capacity constraints in the Southern Region, where we have experienced significant traffic growth.”

How much market growth? “Approximately 80% of our growth capacity budgeted this year is targeted at the Southern Region,” Fritz said. “Our most significant project in the region is constructing our Brazos Yard,” which began in January 2018. “The yard is located at a highly strategic point in Texas and will provide critical capacity supporting a wide variety of traffic, including petrochemicals, plastics, consumer goods, and cross-border traffic.”

That was then.

Now, more than one year later, something or some group of things have happened. Railroad strategic planning often doesn’t occur in a straight-line fashion.

One critical change was that UP brought in a new former CN PSR (Precision Scheduled Railroading) officer—Jim Vena. He now heads up UP’s entire PSR conversion—Unified Plan 2020— as Chief Operating Officer. He had not been part of the original Brazos decision.

Second, the climate for international trade and the expectation for a rapid expansion of petrol-chemical and plastics in UP’s Southern Region may have been blunted by changing tariff trade realities. Some economists sense a 2019 slowdown in the energy-based chemical growth rate—perhaps dipping toward a 2.5% to 3% growth slope.

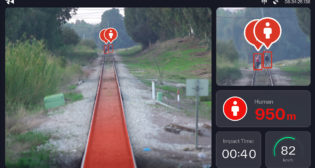

Third, the operating plan under new leadership is now more focused on shifting toward much longer train lengths. In Texas and elsewhere along the UP network, train capacity is complicated by short siding lengths of an earlier era, and distant spacing separation between passing track sections. It is tough to run 10,000-foot or longer trains when the sidings are often 7,500 feet or so and spaced too far apart. The result is a restriction on trains per hour that can, with a reliable schedule, pass along the Southern Region and other areas of Union Pacific single-track main line.

Budget Impact of executing UP 2020

In the UP’s PSR approach, capital budgets compete with the need to pay dividends and buy back shares. If the old plan for Brazos somehow now conflicts with the perceived priority for adding more sidings and shorter siding spacing, something has to give way.

Translation? The Brazos project construction timeline can be extended. Deferring capital from a rushed new yard construction allows capital shifting toward the passing track length extensions and the added sidings along strategic high traffic lanes.

In simple math, the engineering cost of extending a siding runs about $2 million per mile if little ground grading is required. Lengthening or adding new sidings where drainage and grading are required can average closer to $3-3.5 million per mile. Thus, allowing for 30 to 40 siding projects is roughly a $100 million or so fund shift. A delay in the Brazos yard project impacts about one-fifth of the yard programming. That appears to be a logical tradeoff in economic terms.

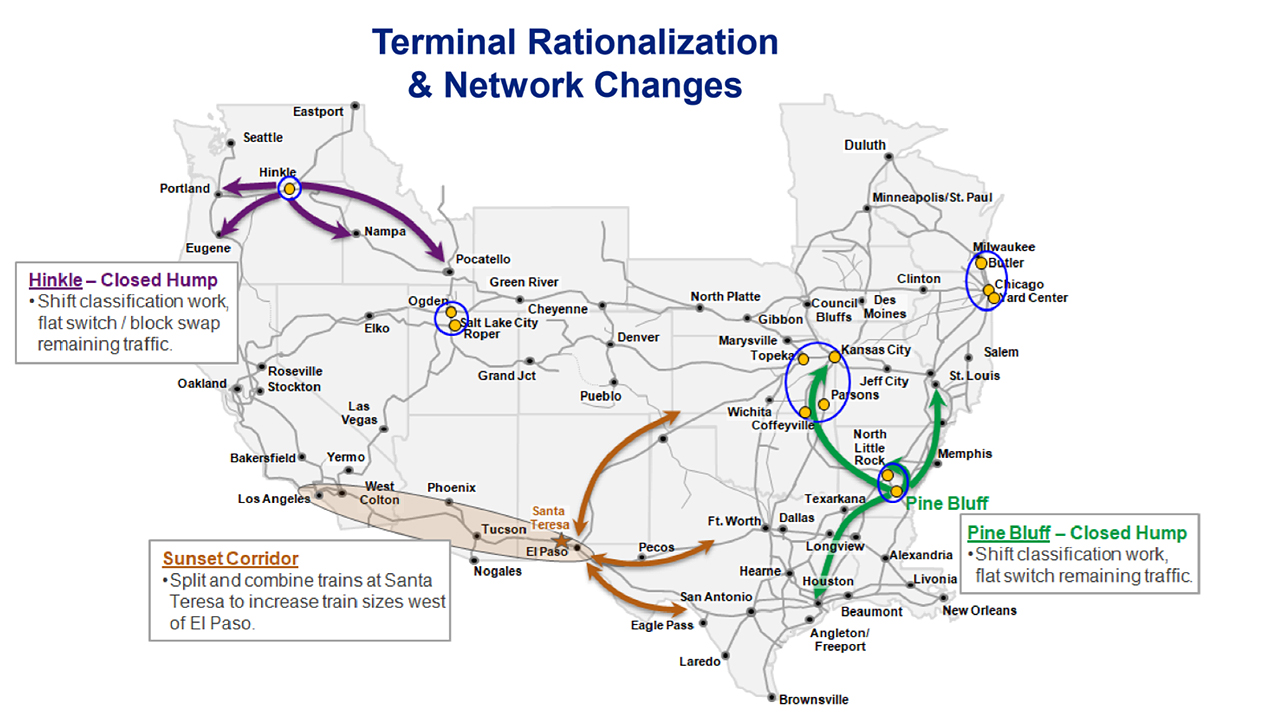

One possible result is that the previously delayed El Paso, Tex., to Los Angeles double-tracking or siding extension program will now be advanced this year. Some funding previously designated for Brazos Yard will instead be directed at improving the Santa Teresa intermodal yard’s longer train handling capability. Other redirected Brazos funds will go to improve siding functionality elsewhere along the multi-state UP network.

Delaying Brazos by a year is a prudent economic approach

To be sure, technically, the company decided to “pause construction”—not terminate the Brazos project.

Nearly one year into Brazos construction, it is still unclear as to the regional role of the network of Houston yards with Brazos yard added. Are selective Houston yards to be closed or re-purposed? Is Englewood Yard, as one example, simply too flood-prone and capacity-constricted by surrounding land uses? That has not been publicly articulated by UP or its board.

Clearly, a yard the size of Brazos as originally designed and publicized has a definite network effect on UP’s entire Beaumont to Corpus Christi network. Multiple computer simulations of operational changes and yard requirements are being examined, this time by PSR experienced hands. The optimum design and use patterns remain a business secret, which is, of course, UP’s right—unless UP is seeking some broad Houston region PPP capital plan funding for yards and track. If so, then it becomes a public discussion.

Across the UP network

The PSR model is clearly de-emphasizing the hump classification yard. The current version of UP 2020 is seeing several hump yard closures such as Hinkle in Oregon and Pine Bluff in Arkansas as displayed on a recently released map. Other yard rationalization changes are being examined in the Salt Lake and Kansas City area as new COO Vena tours the UP system. That is a normal process when new leadership comes on board.

Theoretically, UP management now believes that car humping is most efficient when cars per day are in the 1,200 or higher range. That appears to be a fluid number. It is not a precise yardstick by any means.

In the Houston area, a great deal of UP traffic is industrial commodities, often requiring yard switching. That was the reason originally for some kind of regional rationalization, such as Brazos. The other choice is to physically rebuild and modernize some of the existing older-design UP Houston region yards. This Houston and Southern Region coastal market has been examined and reexamined by UP internally for more than a decade, according to various published UP documents and two State of Texas rail plans in which UP participated. One local study found that heavy industrial cargo accounts for about 84% of Houston’s rail activity. That is a lot of switching. It was expected by all parties to grow given the Permian Energy Basin and surrounding prospects for chemical market development.

Now, with the Brazos delay, does this suggest that UP freight car movements are declining in the Houston area for some reason? Or, that pre-blocking of trains is possibly eliminating a critical mass of former classification humping at UP yards? The facts are unclear.

The 1,200 or so cars per day threshold is interesting because it contrasts with previous UP press releases that Brazos Yard would operate with a capacity of just 1,300 railcars per day. That is obviously right at UP’s current PSR management minimum. This logically calls into question the Brazos original yard design.

According to published reports, UP as of December 2018 had made certain criteria decisions about this hump yards and the marketplace under its emerging PSR plans. “If you look at our utilization of hump yards, it’s pretty is high,” CEO Fritz said. Is the less than 80% rule still in effect as the UP standard? That is unclear.

For the Texas market, in late 2018 Fritz had concluded that from North Little Rock to Pine Bluff to Fort Worth to Livonia to Englewood and Settegast, all of UP’s yards were “at or near fluid capacity. Some of them are above it.” Have longer trains or some other PSR deliverable now changed that situation? That is also unclear.

UP’s first-quarter 2019 presentation slides are not broken down into geographic details. However, it does appear that petrochemical and industrial traffic—very prominent in Texas—are holding up with a 4%t growth rate into 2019. That is close to what the 2018 outlook toward 2020 has been by most regional economists.

So, what has changed? The criteria? The operational measurements and formulas? The customers’ traffic has dropped? All of the above?

No one including the regulators seems to know. The only certainty is that the Brazos yard is not cancelled.