Labor Talks Include a Witches’ Brew

Written by Frank N. Wilner, Capitol Hill Contributing Editor

WATCHING WASHINGTON, RAILWAY AGE OCTOBER 2019 ISSUE: Prepare for the oldest lawfully established permanent floating craps game in America—national wage, benefits and work rules negotiations between most Class I freight railroads and their labor unions.

Desired contract revisions—Section 6 notices in the parlance of the 93-year-old Railway Labor Act—will be exchanged Nov. 1, followed by collective bargaining. Anticipate initial theatrical bluster trailed by a kabuki-like dance leading to substantive negotiations aided by federal mediation and, hopefully, enlightened mutual compromise.

Otherwise, there occurs a strike or lockout—“snake eyes” in dice-game jargon, where Congress imperfectly, and typically to the dismay of both parties, resolves what they cannot. Such intervention is remarkably rare, but this round’s briar patch is particularly barbed.

As rail labor contracts remain in force until revised through collective bargaining or third-party determination, there is no time-clock deadline to reach settlement. The previous round began in January 2015 and concluded peacefully in late 2018, with retroactive revisions.

THE BASICS

Twelve unions representing 140,000 rail workers—some 90% of the workforce—will bargain with the multi-employer National Carriers’ Conference Committee (NCCC), which represents most Class I freight railroads and many smaller ones. The NCCC’s chief negotiator is Brendan Branon, Chairman of the National Railway Labor Conference. On the opposite side will be the unions’ elected presidents, who typically choose among themselves lead negotiators.

Branon is a veteran negotiator recruited last year from Delta Airlines to succeed Kenneth Gradia, who retired. Branon will be joined at the bargaining table by the senior labor relations officers of Class I railroads. While it will be Branon’s first rail bargaining round, airlines also bargain under provisions of the Railway Labor Act, and most of the carrier negotiators have prior experience with their union counterparts.

Branon left Delta with a solid reputation. The Air Line Pilots Association chief negotiator on Delta, Capt. Bill Bartels, told Railway Age that Delta “will be challenged to find someone who is as familiar with pilot issues” in future contract negotiations as was Branon.

Joining BNSF, CSX, Kansas City Southern, Norfolk Southern and Union Pacific at the bargaining table will be CN (U.S. rail operations). CN’s previously different contract-reopening dates have been realigned to those of other Class I railroads at the table, and while CN stands alone with hourly wage rates for U.S. train and engine service (T&ES) employees, the NCCC says “nothing prohibits” CN from bargaining collectively with carriers having trip rates.

Canadian Pacific, with U.S. operations, is not an NCCC member and bargains separately. Many smaller railroads limit NCCC participation to benefits issues.

This round could be one of the lengthier and more difficult, with impasse looming over wage increase demands, healthcare cost sharing and minimum train crew size.

While CSX will participate in national handling for wages, benefits and work rules for all non-operating crafts, and has stated it is aligned with the other Class I’s in its bargaining goals, CSX will limit its participation in national handling to benefits for operating crafts (BLET and SMART-TD), meaning it will not participate in national handling for wages and work rules with BLET and SMART-TD.

WAGES

Downward pressure on wage demands will be exerted by a slower-growth economy; a feared long-term economic impact of the trade war; a permanent shift by electric utilities away from higher-margin rail-delivered coal; and a seven-month, year-over-year skid in carloadings—even excluding coal and grain traffic.

Railroads will emphasize that their employees rank in the top 6% of wage earners nationwide, with average annual compensation—wages plus benefits—of some $122,000. Since 2006, rail wage rates rose by 43% vs. 29% for other U.S. workers; while since 2015, wages of the highest-paid rail worker increased by some $33,000 annually and more than $16,000 for lower wage rungs. But economists predict America’s unprecedented 10-year economic expansion is ending, as evidenced by deteriorating rail traffic.

Unions will cite a profit-boosting pounding down of rail operating ratios; many billions of dollars in stock buybacks and dividend hikes following a $16 billion windfall from 2017 tax reform, spawning rank-and-file resentment; and argue that world-class customer service and safe train operation require a stable, well-trained and motivated work force whose quid pro quo is elevated compensation.

HEALTHCARE INSURANCE

Healthcare costs continue to soar. Studies say the net cost to railroads for providing employee healthcare insurance—plan costs minus employee contributions—is 52% greater than average employee plans; and even with cost sharing, railroad healthcare plans pay some 90% of each member’s family healthcare costs.

Rail negotiators will compare the railroad plan with universally less-generous plans, including those covering congressional staff, whose premiums, copays and deductibles are significantly higher. The message is that if negotiations turn south and Congress legislates a new agreement to end a work stoppage, sympathy for labor’s refusal to shoulder additional healthcare costs may be walking its own picket line. In 1991, a Democratic congressional majority voted to end a strike on terms embraced by railroads.

Unions will argue that for many crafts, railroading is a dangerous occupation with additional health risks from unpredictable schedules, harsh weather environments, being continually on call and frequent stays away from home. They will cite their lower healthcare cost-sharing as having been “purchased” in exchange for previous lower wage hikes.

WORK RULES

As carriers pursue revisions to contractual minimum train crew size, look to Shakespeare’s “Macbeth” to describe that witches’ brew—“double, double, toil and trouble; fire burn and caldron bubble.”

Union activists still call a 1991 agreement reducing three-person crew size to one conductor and one engineer “a bloody shirt to be waved around.” They are in no mood to discuss further crew size reductions until, as they maintain was agreed in 1991, the last protected employee resigns, retires or dies. In their favor, a federal court turned back a 2006 carrier attempt to renegotiate in national handling a ruling that crew consist changes be sought on individual railroads where they were first reached. Since then, the Class I’s have not pursued crew size changes in the two intervening national bargaining rounds.

Notably, when a lone-wolf general committee of the conductors’ union—SMART-TD—reached a tentative pact with BNSF in 2014 to allow one-person crews for non-hazmat trains operating over some 60% of the BNSF network where Positive Train Control (PTC) is in place, ratification failed despite a BNSF offer of lifetime income protection.

Many members are said to be rethinking that “no” vote, realizing vulnerability on seniority districts where protected employees have disappeared, giving carriers other options that may not be so generous in return.

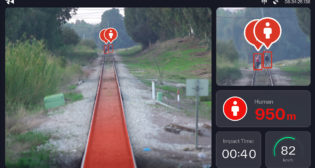

For sure, PTC—defined by the Federal Railroad Administration (FRA) as “integrated command, control, communications and information systems designed to prevent train accidents by controlling train movements with safety, security, precision and efficiency”—dilutes contentions that two crew members always are required for safe train operation.

In fact, the FRA ruled in 2019 that “no regulation of train crew staffing is necessary or appropriate for railroad operations to be conducted safely at this time”—an edict likely to be upheld by federal courts under the Supreme Court’s 1984 Chevron and 1997 Auer doctrines that “deference” be given expert federal agency decisions.

The FRA also exercised federal pre-emption authority to invalidate application of union-encouraged state laws mandating minimum train-crew size within state borders. As for union-sought congressional legislation mandating two-person crews, meaningful support is non-existent, as fewer than 110 of 435 House members have co-sponsored H.R. 1748; and a companion bill (S. 1979) in the 100-member Republican-controlled Senate has but 13 sponsors—11 Democrats and two independents.

Although carriers will not openly talk strategy, an option is to operate some trains with just one engineer, but pay the conductor to be idle and precipitate a contract-interpretation dispute requiring binding arbitration.

Carriers already have embarked on a court strategy to require SMART-TD to engage in negotiation of crew consist in the upcoming bargaining round. On On Oct. 2, the NCCC asked a federal district court in Texas to rule that any dispute over interpretation of the crew consist moratoriums is a “minor dispute” as defined by the Railway Labor Act and thus must be resolved through arbitration.

Separately, Indiana Rail Road, the Association of American Railroads and the American Short Line and Regional Railroad Association have asked a federal district court in Illinois to invalidate a state law requiring two-person crews, arguing that federal regulations preempt any state action against interstate railroads.

A witches’ brew, indeed, calling for savvy negotiating skills on both sides, with recognition that labor and management, rather than being enemies, must collaboratively innovate to protect and grow railroads’ market share against the real enemy—motor carrier encroachment.

Managing change, not blindly opposing it, is the stuff of meaningful, long-lasting job and income protection, as no labor union ever has stopped the advancement of technology—which also is progressing among rail competitors.