Biden ‘Railroaded’ Workers, and Maybe Himself

Written by David Peter Alan, Contributing Editor

The nationwide railroad strike that was threatened for Dec. 9 did not take place. In effect, the Biden Administration and Congress ordered workers to accept the terms of a tentative agreement their unions had reached with the Class I railroads. Members of eight of the twelve unions involved ratified it, prompting two branches of government to collaborate on enforcing the agreement. Labor says the workers who voted to reject the pact were “railroaded” in the traditional sense of the word, but Joe Biden may have “railroaded” himself by alienating one of his party’s most loyal voting blocs—loyal at least until now. It is possible that, even though workers were denied the seven extra days of paid sick leave they wanted, Biden might lose his own job two years from now in the fallout.

March 23, 1932 was a big day in American labor history. It was the day that the Norris-La Guardia Act, which prohibited courts from granting injunctions to end non-violent strikes in the private sector, was passed. Named after its two progressive Republican sponsors (yes, there were such people then), Sen. George W. Norris of Nebraska and Rep. (and future Mayor) Fiorello H. La Guardia of New York, it was the first of several victories that the labor movement would win, especially during Franklin D. Roosevelt’s “New Deal” Administration. Government, in the form of courts, could no longer routinely order workers to end their job actions. Today’s Executive and Legislative government branches can still exercise similar power from time to time, and labor might not take it all that easily.

Capitol Hill Contributing Editor Frank N. Wilner’s comprehensive reporting in Railway Age on Dec. 2 (President Biden Signs H.J. Res. 100 into Law) told the story. Biden and outgoing House Speaker Nancy Pelosi paid lip service to the concept of sick leave and reluctance to send railroaders back to work with only one additional day off per year, but they did it anyway. Wilner also quoted Pelosi as saying, “Going to a proctologist is not a reason why people would take a day off,” a statement that could bring her expressed reluctance into question.

As we also know, the results came out as expected. With the back-to-work resolution considered separately from the one that would mandate seven sick days, it seemed clear before the votes were taken that the former would pass and the latter would not make it past the 60-vote hurdle in the Senate.

In a follow-up commentary headlined Will Bureaucrats Invade the C-Suite? which ran on Dec. 5, Wilner said: “In negotiating amendments to national labor agreements, carriers handed their unions a public relations victory by steadfastly resisting a request for paid sick leave. Their flimsy defense was that the unionized workforce already has paid vacation and personal leave days, even though such absences require advance permission, while illness arrives randomly. Harsh railroad attendance policies fare no better in the public’s eye than those Elon Musk sought at Twitter.” While this writer does not necessarily agree with the conclusion in Wilner’s commentary (we occupy different points on the political spectrum), the statement quoted above appears to have hit its target.

In his own commentary, posted the same day and bearing the musical headline What a Difference a Day Makes, Railway Age Financial Editor David Nahass summed up two differing views of the situation: “The railroads have attempted to redirect the conversation to being about the largest short-term increase in compensation over the changing lifestyle of the American worker. The raise is important, the paid sick days are important, the opportunity to handle family or personal emergencies is important … Unfortunately for the unions, consumer sentiment is generally unkind. While the other unions won’t cross the picket line, union solidarity is not a priority in people’s lives—less so when it impacts their pocketbook and weakens an already fragile supply chain.”

Nahass’s perspective appears to summarize the debate, but times might be changing. The model for union aspirations might also be changing, which could prove to be a factor in a nation where political circumstances and the calculations stemming from them could be changing just as rapidly.

Are Labor’s Priorities Changing?

When I studied labor relations as part of an MBA program more than a half-century ago, it was clear that unions had only one set of goals for their members, and it centered on money. All unions seemed to follow in the footsteps of Samuel L. Gompers, the cigar maker who served as head of the American Federation of Labor (AFL) from the 1880s until the mid-1920s. According to Gompers, what workers wanted was “more”: more pay, more fringe benefits, and a shorter workday, which would give them more time to enjoy what their wages could buy. The Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) held similar views, and the two groups merged in 1955 into the AFL-CIO. Labor has moved into new areas like the public sector, but its overall influence has declined in recent decades. Still, the vast majority of union members have been staunch Democrats, and labor support has helped that party to get its candidates elected, at least until now.

During Gompers’s time, the unions affiliated with the AFL represented mostly skilled workers with trades and gained dominance in the labor movement over unions with more-radical ideas, like an ideology that life should be better for workers and everybody else, and unions had a role to play in helping life-improvements become reality.

There might be a change coming, though, and the developments in the current situation for rail labor seems to provide a case in point. President Biden has always touted his support for labor, and he voted against forcing railroad workers back to the job during a similar situation in 1992, when he was a U.S. Senator. Labor Secretary Marty Walsh, who took an active part in the effort to settle the dispute, has strong union credentials. He started as a laborer and became president of his local before he was elected to the Massachusetts House of Representatives. He completed his degree at Boston College while serving in the legislature and was later elected mayor of Boston.

It’s difficult to fault old-school pro-labor politicians for their performance, especially when they were able to secure substantial pay raises for railroad workers. The unions did not complain about the financial side of the deal they got; the rank-and-file who voted it down complained about the lack of sick days and other rules that kept them at the beck-and-call of the railroads, practically at all times.

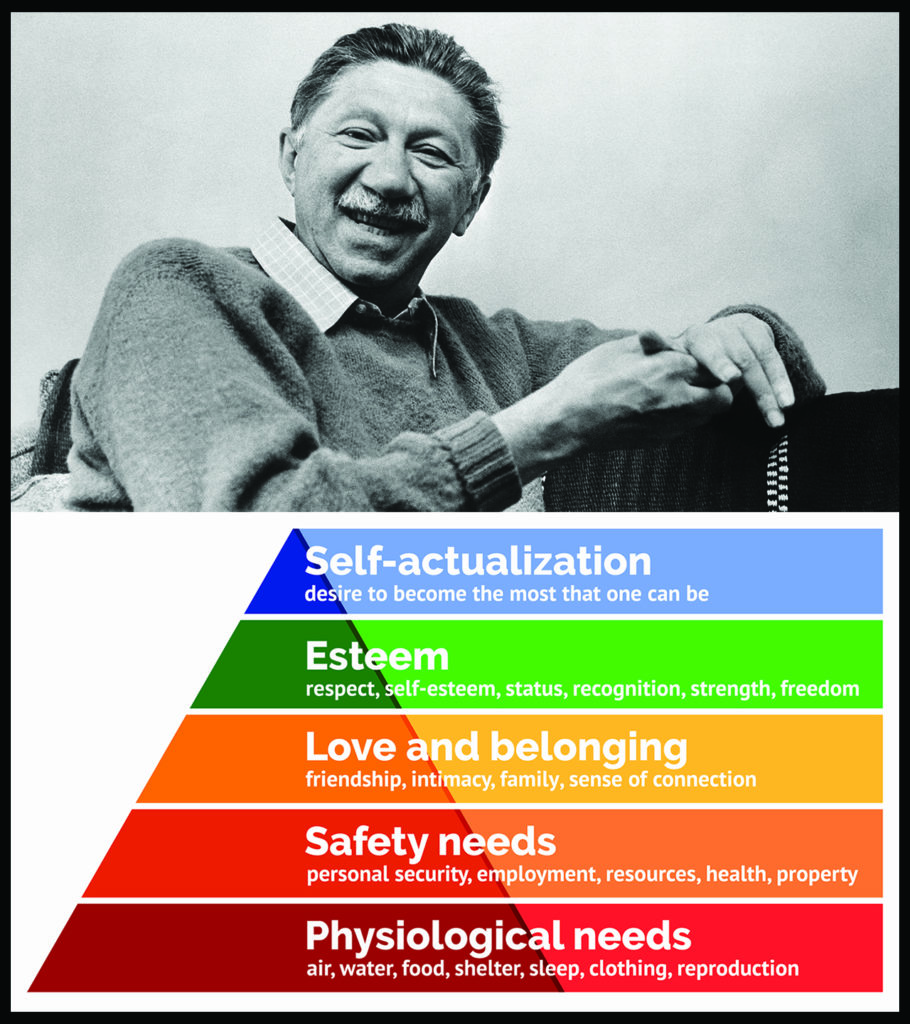

Maybe in this increasingly post-industrial world, more workers are advancing along Abraham Maslow’s famous “Hierarchy of Needs” by shifting their focus from earning enough money to survive, to having more control over their time and similar lifestyle issues.

On Dec. 1, CNN host Jake Tapper interviewed Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg and attempted to pin him down about the importance of paid sick leave, since the workers would not get the seven days they had hoped for (they had originally asked for 15). Buttigieg adroitly sidestepped the issue in classic political style by touting other accomplishments of the Biden Administration for labor. His answer did not seem to satisfy Tapper, and it would probably not satisfy labor either, affirming Wilner’s pronouncement of a public relations victory for unions.

The Alternative, and a Political Calculation

Recent developments demonstrate that the spirit of dissatisfaction still lives among at least some union members, the spirit that inspired their votes against the tentative agreement that Congress and the Biden Administration enforced.

The hotly contested election among BLET members received extensive coverage. The concession statement by outgoing President Dennis R. Pierce (cited by Frank N. Wilner in his coverage) said that Edward A. Hall had received 4,331 votes to 3,822 for Pierce; a 53-47 split, even though turnout was low.

That can happen in “regular” elections, too. A protest resulted in an order for a new election, but Pierce conceded and withdrew from any further contest. Whether a “do-over” would have improved turnout or led to a different result remains unknown. Presumably, if Pierce thought so, he would have run again, but that may never be known.

Wilner cited an allegation that a Socialist organization outside the union was favoring Hall. It is difficult to see how such an endorsement would have changed the outcome. Of the members who voted, enough of them chose Hall that, barring a bombshell during the campaign, it is unlikely that the result would have been different.

One interpretation of the result is that a sizable component of the membership was deeply disappointed in the lack of improvement in work schedules within the tentative agreement that was given the force of law.

There is another “law” that might influence future events: the “Law of Supply and Demand,” one that no legislative body can repeal. It has been reported that Union Pacific (UP) is considering scheduling more sick days for its employees, perhaps even considering the benefits of the move to exceed the costs. It’s far too early to see whether the railroads will actually implement such a policy, but it could be worth their while.

Throughout the history of railroading, railroaders have been dedicated and proud, regardless of their craft or the management job they hold. Still, if work schedules driven by the “lean and mean” approach that comes with Precision Scheduled Railroading (PSR) creates such an unpleasant work environment that workers have trouble tolerating it, the inevitable result will be more workers quitting and fewer new ones coming on board. In that event, management will have no choice but to give the workers what they want. If they are already satisfied with their pay, that means fringe benefits like more sick days.

It’s not clear if there will be any changes in that direction in the future, but It’s quite clear that any such changes will not change the attitude of union members toward an Administration and a Congress that forced railroad workers to live with rules many voting members rejected.

The workers didn’t receive the additional sick days because the Administration and Congressional leaders split the resolutions before Congress, rather than tying the back-to-work issue to the sick-days issue. In his first-cited commentary, Wilner gave several reasons why granting labor’s request for more paid sick days would make sense. Another reason he mentioned is that the carriers could easily afford to give their employees additional sick days. Class I railroads are posting robust profits, and there are so few of them that they can pay monopsony-level wages to workers and charge monopoly-level rates to shippers, subject only to competition from the trucking industry.

Politically, tying the two issues together in a single resolution involved a level of risk that Democrats appeared unwilling to take. The carriers could probably afford the sick days, but would they have held the line and taken a strike? There is no way to know for sure, but the Democrats could have blamed the Republicans for refusing to give railroad workers a fringe benefit that most other workers have. That may have produced long-term gain for the workers, but would have required a short-term risk for Democrats that seemed like too much of a gamble.

The gamble might have gone the other way, with Biden and other Democrats losing. Labor has historically been a vital part of the coalition that has helped Democrats attain victories over the years. Labor has been on the decline for the past several decades but seems to be gaining some ground since the COVID-19 virus struck. How far labor’s momentum will go remains to be seen.

Long-Term Loss for Biden and the Democrats?

There is no doubt that labor, especially rail labor, felt that Biden and other Democrats had let them down. Even if labor has lost some of its influence over the years, it still has enough to make a difference when an election is closely contested. Labor has not historically been able to generate campaign contributions to match the magnitude of corporate donations, but it can still supply plenty of volunteers for grassroots campaigning and taking voters to the polls. How much money and effort unions and their members will supply in the next election depends on how much enthusiasm those unions can muster to vote for the Democrats in 2024. At the moment, anyway, the rail unions don’t seem very enthusiastic.

Biden is considering running for re-election, and he will need strong labor support. He has several factors going against him. Whether fairly or unfairly, many voters believe that he is too old to run for another term. If he runs, wins, and lives through that term, he would be 86 when he leaves office. His approval ratings have been under water since mid-2021, always considered a bad sign when it comes to a re-election campaign. It also does not appear that Vice President Kamala Harris has caught on with the public, which would adversely affect her electability, running with Biden or on her own.

To be fair to Biden and the Democrats, they did much better than expected in last month’s elections. They picked up some governorships, and the Republicans won the House only by a slim margin. They also held onto the Senate, an unusual accomplishment in a midterm election. Raphael Warnock’s victory in Georgia did not give Democrats as much of a boost as they wanted, due to Krysten Sinema’s decision to leave the party and become an Independent, but the “red wave” that Republicans expected never materialized.

It appeared that much of Biden’s hope for 2024 stemmed from an expectation that Donald Trump could be his opponent in a re-match. That prospect now appears far less likely than it did before the 2022 midterm election, especially since Trump is potentially facing criminal charges (obstruction of an official proceeding of Congress, assisting an insurrection, conspiring to defraud the United States, seditious conspiracy) by the Department of Justice following January 6th Committee recommendations. Many Republican candidates who got Trump’s endorsement, from Herschel Walker in Georgia to Mehmet Oz in Pennsylvania to Kari “Trump in Heels” Lake in Arizona, lost their races. Other Republicans are seeking to distance themselves from a former President they consider toxic. Trump’s star in the party is burning out as quickly as it rose in 2015 and 2016.

Yet, without strong and enthusiastic support from labor, Biden’s position could be weaker than it was in 2020. Even if Trump is gone—relegated to the dustbin of history as footnote and prohibited from holding any public office—against a different Republican, Biden’s chances of winning could plummet. There is another Republican on the scene: Gov. Ron DeSantis of Florida. Politics can change considerably between now and the official start of the 2024 campaign, but now it looks like DeSantis is the only strong nominee prospect, and he doesn’t carry Trump’s baggage.

In short, Biden might have “railroaded” himself with labor, and DeSantis or another Republican could reap the benefits.

David Peter Alan is one of America’s most experienced transit users and advocates, having ridden every rail transit line in the U.S., and most Canadian systems. He has also ridden the entire Amtrak network and most of the routes on VIA Rail. His advocacy on the national scene focuses on the Rail Users’ Network (RUN), where he has been a Board member since 2005. Locally in New Jersey, he served as Chair of the Lackawanna Coalition for 21 years, and remains a member. He is also a member of NJ Transit’s Senior Citizens and Disabled Residents Transportation Advisory Committee (SCDRTAC). When not writing or traveling, he practices law in the fields of Intellectual Property (Patents, Trademarks and Copyright) and business law. The opinions expressed here are his own.