Sure-Footed Sorting

Written by William C. Vantuono, Editor-in-Chief

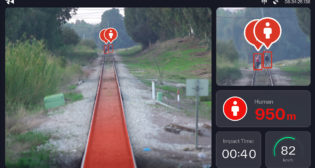

Photo by Apex Rail Automation

RAILWAY AGE, JUNE 2021 ISSUE: Through technology, railroads can say bye-bye to classification yard bottlenecks.

Classification yards remain a backbone of railroading, mostly for “loose car” carload traffic, which accounts for approximately 60% to 70% of total rail traffic (excluding intermodal). Gravity-hump or flat-switch, railroads are improving class yard efficiency, reducing car dwell time and the tendency for such a facility to become a bottleneck on an otherwise-fluid system. That’s what process control systems do. Among the key suppliers in this space are Apex Rail Automation (formerly Vossloh Signaling), PS Technology, RailComm LLC and Trainyard Tech LLC.

Apex Rail Automation President David Ruskauff, with a software background, offers some historical context. “In the 1990s, there was development of what was called ‘object-oriented programming,’” he recalls. “It was based on breaking things into different functions, capabilities and objects, from a programming standpoint. It allowed you to take objects and combine and recombine them in different ways to come up with different solutions. In the ’80s and ’90s, if you did a control system or any type of automation system, it was large, monolithic. You had to install complex power and comm systems. Everything was fixed in how it was assembled and what it was capable of doing.

“We started in the early days of Global Rail (a predecessor company) of splitting components into separate modules, whether they had to do with control software, DTMF (Dual Tone Multiple Frequency) decoding, audio boards or train detection. We split them into separate modules, so that we could combine them in different ways for different types of problems and solutions.”

Fast-forward to today. Apex’s MYA (Modular Yard Automation) technology incorporates switch machines, train detection and control and communication software, all built into different modules. “We’re able to offer solutions that start from a single switch,” Ruskauff explains. “Let’s say you’ve got a main switch coming in and out of the yard. We can put DTMF capability directly into the switch, so that crews coming off the main line can key themselves into the yard and basically not have to stop the train to hand-throw a switch. Same thing for departure. We can automate all the switches in a yard.”

Apex’s RailMaster, described as “a PC-based software system for controlling switches,” has been employed for yard automation. “We provide NX (entrance-exit) automation for receiving and departure yards, moving trains within a yard facility,” Ruskauff says. “Our first system was in Mobile, Ala., for a CSX flat-switch yard. We took the RailMaster software, and instead of putting it into an office environment for a yardmaster or a dispatcher, we put it into an outdoor-rated computer, a kiosk where the people on the ground can set their routes and lineups in the yard at a touchscreen computer. They walk up to the top of a ladder, and send cars into different storage tracks. If you think of a ladder that you’re going to be switching on, the top of it is always an entrance. All storage tracks are exits. Following our very first installation in Mobile, we created a method within the RailMaster software to input a list of destination tracks. And in a lot of these yards where we’ve installed this, they’ve gone to a single-person crew with RCL (remote-control locomotives). The person on the ground with the beltpack inputs the switch list, lines up the first one, and starts cutting cars off and kicking them down. Once the cars are rolling and past the switches, the system advances to the next one and lines it up. There are no manual switches or movements. It’s much safer.”

For RailComm, business has been brisk, says President Joe Forgione. “We remained fully operational during the entire pandemic,” he notes. “Given our skillset and our infrastructure, we operated mostly remotely, but that’s because we have the ability to support our customers through the cloud. Our people can work pretty much from anywhere.”

In 2019, the Georgia Port Authority selected RailComm as the yard management system provider for the new Port of Savannah Multi-Modal Connector. RailComm’s automation piece, compared to the overall project size, is small but significant. “The yard of the future is here, today,” says Forgione. “Everybody is waking up to the fact that you would never build a new yard anywhere, whether it’s at a port or intermodal facility, without fully automating it.”

Port and intermodal projects are largely done as P3s (public-private partnerships). As a provider of the yard automation technology, RailComm finds itself as part of the consortiums that bid on these projects. “Depending on the scope of the project, we are a subcontractor bidding on the automation piece,” Forgione explains. “Many times, we get involved before the project goes out for RFP, to help write the requirements. So there’s a large project management aspect in which we get involved to put all the pieces together.”

What Forgione calls RailComm’s “secret sauce” is its multi-purpose DOC® (Domain Operations Controller) software platform. Its primary function in a yard application is lining switches. “All that can be done from a remote, safe and secure location,” says Forgione. “Usually, that’s in the yard office, though we’re beginning to see more and more railroads cluster locations, with the ability to manage multiple yards from a centralized location. In the very early days—and RailComm has been around for more than a decade—there were push-button switch control panels within the yard that eliminated hand throws, although, unfortunately, railroads are still doing a lot of that. Then we moved to a software platform from a computer within a central office. Now, with smart mobile devices like tablets and phones, we offer, through a secure interface, the ability to throw a switch or activate blue flag protection from within a yard, rather than walking to the switch or to the end of the track.”

When RailComm was founded, the driving factor behind yard automation was mostly about efficiency, reducing dwell time. “It could take, for example, six hours to build a train, manually lining switches,” Forgione recalls. “We showed that, with automation, it could take only three hours. So, we would build a case, and it made a big difference, in reducing head count and getting dwell time down. But now, railroads are realizing that the driving factor is safety. It’s moving from a secondary requirement to the primary one. I like to use this example: On an airport tarmac, how many people do you see walking around? Virtually none. When you look at railroad safety, what’s the price of somebody getting injured or killed? It’s a big deal. We have many industrial customers who are looking to improve safety as well as efficiency. There are actually more industrial yards than Class I yards in the U.S. They’re a big opportunity, the next wave of rail automation.”

The biggest technological development in yard automation is flexibility, “the types of devices you can control, and from where they can be controlled,” says Forgione. “It used to be that every yard was a silo, individually managed with its own infrastructure. Railroads are now looking at consolidating yard control into a single location, managing them from the cloud, much like we offer with our dispatching business. We have 120 short lines managed out of our cloud. Once you get to the point where it’s in the cloud, you have the ability to begin to move employees around. I see that as a key trend.”

Forgione, in many respects, is a futurist, always questioning the status quo, identifying where the industry can do better. One area of particular interest is FRA regulations, which he feels are trailing available technology. The FRA, under the leadership of former Administrator Ron Batory, made progress embracing modern automation technologies, looking at making adjustments to testing and inspection rules.

“I think we’re starting to see much more openness to it,” Forgione says. “A lot of data is being collected and automated using technology as opposed to paper forms. Railroads are starting to use intelligent devices to capture data. In terms of control, everything we do falls into the purview of what the FRA allows. Say, for example, you wanted to automate obtaining a movement authority before the train moves out, as opposed to having the conductor talk to a dispatcher. That would be something the FRA would have to get involved in. It falls into the same category of all this discussion about one- and two-person crews—what can be put on board, and how it can work.”

A combination of “rail yard knowledge and self-teaching AI (artificial intelligence) can lay the groundwork for optimizing operations,” says PS Technology. The company’s SwitchPro™ platform automates yard operations previously conducted through manual effort or legacy systems. PST offers three Switch Pro™ classification yard process control systems: HPC, FPC and NX. All “utilize real-time, web-based health and monitoring systems that provide insight into terminal automation operations, such as utilization and efficiency, as well as alerts when equipment has failed.” PST says it has deployed more than 50 terminal process control systems, and is Union Pacific’s sole-source supplier.

PST’s HPC (Hump Process Control) consists of real-time process control machines communicating with distributed IO. The Dynamic Hump Yard Speed feature “allows for a 20% increase in throughput, without sacrificing misroutes.” HPC also includes AEI Integration for work list validation and minimizing downtime during classification. ML (machine learning) algorithms “allow for maximized coupling performance in all weather conditions.” Event playback and improved logging “support increased accuracy when troubleshooting and diagnosing failures.” HPC’s safety features include Dynamic Cornering Protection, Enhanced Presence Detection, Empty Track Logic and Contamination Detection that, among other functions, “minimize cornerings, derailments and rollouts.”

Throughout the pandemic, installation and upgrade work for Trainyard Tech LLC’s CLASSMASTER™ Process Control System, and for its ROUTEMASTER™ NX Control and SHOVEMASTER™ Flat Yard Control systems (which are built on the same platform as CLASSMASTER™), didn’t let up, according to President John Aliberti. “We’re doing a lot of software and hardware changes, as our customers have been making many upgrades and changes to their yard track configurations to run more efficiently and fluidly,” he says. “They’ve been doing everything from receiving and departure yard changes to rearranging tracks and switches to get trains over the hump faster. They design the physical changes, and then come to us to modify or upgrade the process control system. We recently finished upgrading Conrail’s Oak Island Yard (Northern New Jersey), and CSX’s Selkirk (N.Y.) Yard. We’re already well into upgrading CSX’s Radnor Yard (Nashville). It’s just been non-stop. We’re busier now than we’ve ever been.”

In terms of technological advancements, Trainyard Tech has been transitioning to “system virtualization.” “Instead of having multiple processors or computers with different functionalities, we’re now using one to three servers with virtual machines,” Aliberti says. “This reduces the system’s physical footprint while enhancing processing power. We’re able to do more things in a smaller box. Based on what our customers want, we’ve improved our algorithms, and added automation. We’ve added soft calibration, which reduces the amount of maintenance. Soft calibration is really automatic calibration, where the system self-tunes.”

Trainyard Tech has been in business for 18 years. “Years ago, when we designed a yard system, we would have several computers, each designated for different operations. The main process control would be handled by what we called the host, and we would have other computers to interface to external systems, like the railroad’s car inventory system. We would build a rack that would have maybe six to eight or more computers for other operations, like radio communications. Now, we’ll put all of them into smaller servers as virtual machines. One box, multiple machines—virtually.”

Computing power has expanded exponentially. It has allowed suppliers of all types of railroad technology to, in simple terms, fit more into a smaller package. Multiple redundancy can be built into one machine, rather than needing multiple machines to provide multiple redundancy.

“In our internal network for supporting all these systems, in the past, we would actually have a physical computer in-house for every project,” notes Aliberti. “There was a lot of maintenance required, especially when we were making changes. We of course have to test every change before we put it into the field. Well, now we have all that virtualized in a couple of large servers in our office. I call them large not because of their physical size, but because of how powerful they are. We’ve got more than 100 virtual machines running in them, and we can run tests from anywhere. Most of our people can work from home now. We can all access our internal systems or any system in the field through our network.”

Because of this functionality, during the COVID-19 lockdown, Trainyard Tech was able to do much of its field work remotely. “We didn’t have to go out into the field very much,” says Aliberti. We were able to do a lot of the work we normally do on site. It worked out well, as far as reprogramming a customer’s system. The railroad would make the physical track changes, and then we went into our system to reconfigure to what they needed. We were able to watch everything the railroad was doing, remotely. We ran tests jointly, and were able to operate 24 hours a day, if needed.”

This is what the post-pandemic “new normal” looks like for railroads, and for suppliers in the technology space: Working remotely, using the available communications tools, less travel, more flexibility, higher productivity, and lower operating expenses. That leaves more time and resources for important functions like research and development. It also allows for more time to be responsive to customers.

“All of our people have done very well through this situation,” says John Aliberti. “The railroads have also adapted well to it.”

That’s a testament to the railroad industry’s resiliency.